The Mapping Journey alla Biennale e la riscrittura delle nuove odissee

The Mapping Journey alla Biennale e la riscrittura delle nuove odissee. Bouchra Khalili porta a Venezia la voce dei migranti

The Mapping Journey alla Biennale e la riscrittura delle nuove odissee. Bouchra Khalili porta a Venezia la voce dei migranti

English translation below

In quel luogo a suo modo già riscritto mille volte dalla Biennale, le Corderie dell’Arsenale, ci s’imbatte in The Mapping Journey Project e sulle prime non si capisce la meccanica dell’installazione, che una vasta riscrittura della narrazione dei viaggi dei migranti. Degli schermi giunge un comento sonoro senza alcuna musica, nessuna luce particolare, una ricerca di essenzialità, quasi una conversazione sotto voce intorno a una tazza di tè.

Perché non c’è un solo tocco di drammatica, una piega di vittimismo, alcuna autoindulgenza per l’odissea intrapresa, solo una voce fuoricampo e calma che accompagna l’immagine: una mano che impugnando un pennarello traccia su una carta del mondo (nostro emisfero) le tappe del viaggio. E che viaggi: un sudanese che attraversa orizzontalmente il Sahel, dal mali torna indietro verso il Niger, poi arranca per mesi e mesi in Libia, finalmente riesce a partire alla volta dell’Italia. Sbarca coi compagni esausto, chiedono dove sia Roma, quella Roma caput mundi a cui portano tutte le strade. I pescatori in cui si imbattono restano di sasso: a parecchie ore di autobus possono raggiungere un’altra Roma, quella d’oriente, la Costantinopoli fattasi Istanbul. E poi chissà, forse da lì…

È così che si viaggia, senza bussole e navigatori satellitari, su gommoni o scafi scassati, si sbaglia rotta facilmente, e gli errori sono scoperti solo alla fine. Del sudanese sappiamo solo, quando finisce il suo racconto, che si è dovuto fermare ancora a Istanbul e spera non più di arrivare un giorno a Roma ma di trovare un passaggio aereo per l’America. Chissà.

A Roma invece approda un ragazzino del Bangladesh. La sua mano disegna sulla carta un su e giù continuo e su distanze che intimoriscono anche i viaggiatori più esperti. Ha quattordici anni quando parte da Dacca, in aereo raggiunge Mosca, da lì Skopje. Ma, in Macedonia riconosce che i miei documenti erano un pochino (somehow fake) falsi e lo rimandano indietro. Rispedito a Mosca, da lì riesce a tornare a Dacca. Ha un conto in sospeso con il trafficante che lo aveva spedito nei Balcani, la sua rotta non ha funzionato ma i soldi – i risparmi dell’intera famiglia – se li è presi. Oplà, come una capriola di cui sono capaci solo i personaggi delle fiabe, si cambia continente e viene allora messo in viaggio per il Sudan.

Da lì comincia uno zigzag che lo porta in Ciad, Niger, Mali. Torna sui suoi passi verso il Niger, e rimane bloccato nel nord, arrestato e incarcerato per mesi. Che fare, in una prigione di Agadez, dove non parla la lingua, non conosce nessuno, senza ormai un soldo, a quattordici anni? Sapevo che Dio mi stava vicino, e tanto bastava per tirare avanti. Dopo tre mesi di cella, il capo della polizia, forse per sfruttarlo, forse riconoscendo una determinazione luminosa in quel poco più che bambino, lo prende a lavorare per sé. Quanto basta per uscire e fare qualche spicciolo.

Passa molto tempo prima che possa rimettersi in cammino. Entra in Libia, in quel far west pericolosissimo e speso mortale che è il dedalo di piste che portano a nord, in balia di trafficanti locali spietati. È un bengalese, piccolo e fragile, ma tenace, e arriva alla costa. Il Mediterraneo ce lo descrive non come l’alba della propria speranza, l’anticamera dell’ultima corsa, ma come un posto di tappa qualsiasi, senza gloria, ancora una non-meta. Trascorre circa un anno in Libia, lavorando dovunque trovi qualcuno che gli dia un piccolo compenso – più che altro da manovale.

Ma questo eroe da de Amicis, da Dagli Appennini alle Ande versione non letteraria ma reale, e da XXI secolo, ha già dato in abbondanza e finalmente arriva il suo giorno. Riesce a salire su uno scafo e sbarca a Lampedusa. Minorenne, viene preso in cura da un programma per minori non accompagnati, gli viene insegnato l’italiano e morale della favola, happy end, lavora oggi come cameriere a Roma. Lui ci è arrivato, e dice

“l’ho fatto per la mia famiglia, per mandare un aiuto dall’Italia a loro che sono in Bangladesh”.

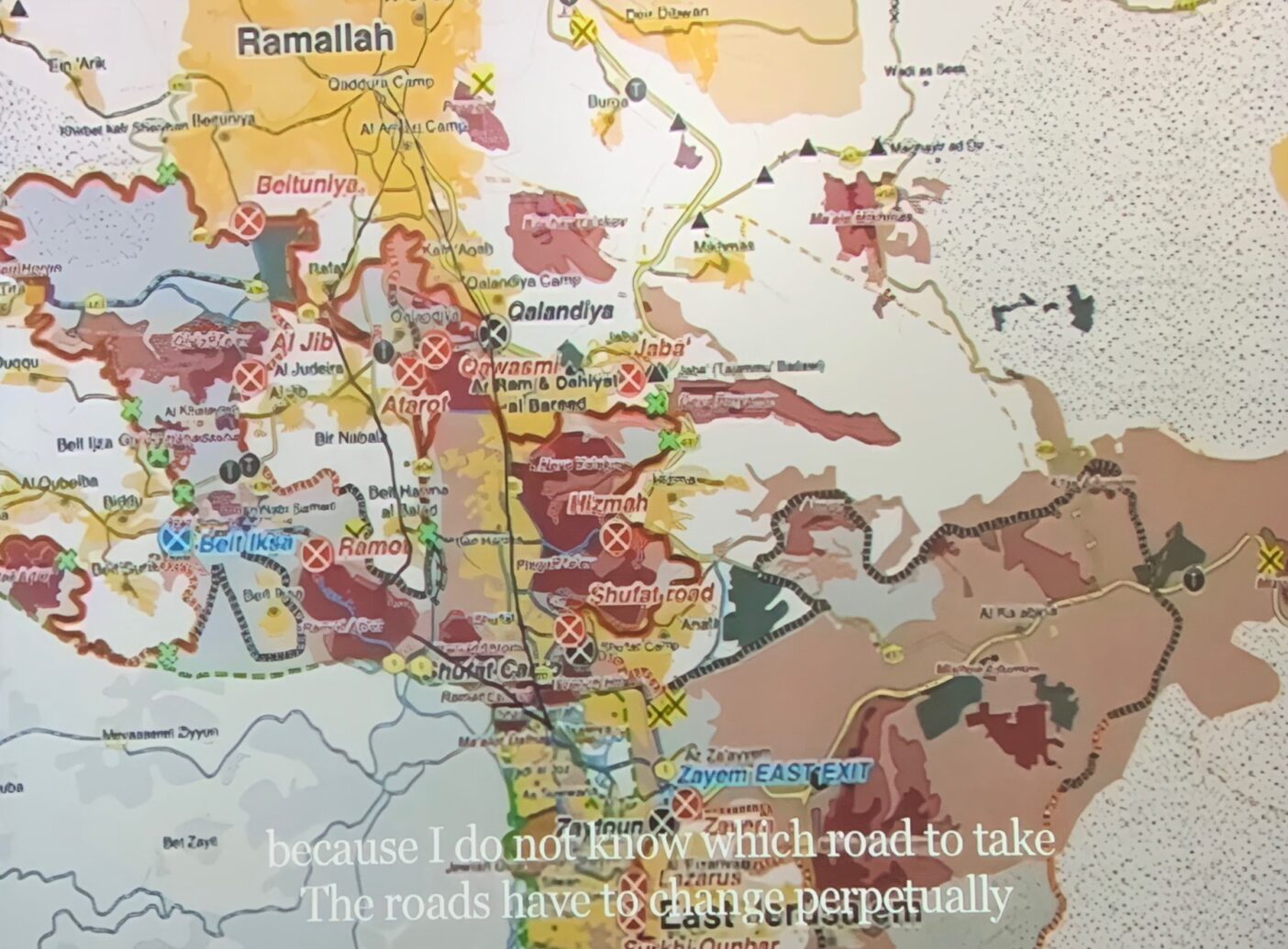

Da altri schermi si dipanano altri racconti, altri percorsi intercontinentali affrontati senza un quattrino e tra mille pericoli. Uno solo è un micro-viaggio che si svolge nel raggio di pochi chilometri. Ma è il più impressionante in quanto a cambi di direzione continui, a ostacoli che si incontrano ogni dove, quasi metro dopo metro, al rapporto assurdo tra distanza coperta e tempo impiegato: è quello che, quotidianamente, un palestinese della Cisgiordania deve affrontare per andare da un villaggio all’altro, tra strade riservate ai coloni israeliani, check points, costruzioni di cemento sulla strada, militari con la stella di David che a sorpresa interrompono o invertono il percorso, e via dicendo. Ma non ci scoraggia mai e si resta pe rla strada.

La Biennale di quest’anno vale già solo per sedersi all’Arsenale e seguire passo passo questi eroi del nostro tempo.

Ci rendiamo conto che questi migranti sono i moderni, avanguardisti, più aggiornati di noi: cosmopoliti, capaci di trovare la strada tra mille difficoltà, a sbrogliarsi con le lingue, a dominare il mondo globale. Nessun master nella migliore delle università può preparare ad affrontare la vita del secolo come loro hanno imparato.

La registrazione delle loro voci, l’idea di farci vedere solo un pennarello e una mappa che prende a stento l’aspetto di una tabella di marcia, sono di Bouchra Khalili, artista franco marocchina che vive a Vienna. Una mediterranea, un’araba, un’europea. Eppure, The Mapping Journey Project è stato finanziato dal Museom of Modern Art di New York, in America, non dall’Unione europea o da una delle tante fondazioni arabe, quando invece dovrebbe essere mostrato in ogni scuola o in ogni parlamento dell’Europa. Ma vedere questi video è come guardarsi allo specchio – e non ci piace.

ENGLISH VERSION

Bouchra Khalili brings the voice of migrants to Venice

In the Biennale Corderie dell’Arsenale, we come across The Mapping Journey Project . At first we do not understand the mechanics of the installation, a vast rewriting of the narrative of migrants’ journeys. From the screens comes a sound commentary without any music, no particular light, a search for essentiality, almost a whispered conversation around a cup of tea.

Because there is not a single touch of drama, a hint of victimhood, any self-indulgence for the odyssey undertaken. We hera just a calm voice-over that accompanies the image: a hand holding a marker traces the stages of the journey on a map of the world (our hemisphere). And what journeys: a Sudanese who crosses the Sahel horizontally, from Mali goes back to Niger, then struggles for months and months in Libya, finally manages to leave for Italy. He disembarks with his companions exhausted, they ask where Rome is, that Rome caput mundi to which all roads lead. The fishermen they come across are stunned: several hours away by bus they can reach another Rome, the one of the East, the Constantinople that became Istanbul, and then who knows, maybe from there…

This is how one travels, without compasses and satellite navigators, on dinghies or broken-down boats, one easily gets lost, and the errors are discovered only at the end. The only thing we know about the Sudanese, when he finishes his story, is that he had to stop in Istanbul and hopes no longer to get to Rome but to find a flight to America. Who knows.

Instead, a boy from Bangladesh manages to reach Rome. His hand draws a continuous up and down on the paper and over distances that intimidate even the most experienced travellers. He is fourteen when he leaves Dacca, by plane he reaches Moscow, from there Skopje. But, in Macedonia he recognizes that “my documents were a little fake”. Sent back to Moscow, from there he manages to return to Dacca. He has a credit to get from the trafficker who had sent him to the Balkans, his route didn’t work but he had taken the money – the savings of the entire family. So, like a somersault that only fairy tale characters are capable of, he changes continent and is then sent on a journey to Sudan. From there he begins a zigzag that takes him to Chad, Niger, Mali. He retraces his steps towards Niger, and remains stuck in the north, arrested and imprisoned for months. What to do, in a prison in Agadez, where he doesn’t speak the language, doesn’t know anyone, without a penny, at fourteen? “I knew that God was close to me,” and that was enough to move on. After three months in prison, the police chief, perhaps to exploit him, perhaps recognizing a luminous determination in that little child, hires him to work for himself. Just enough to go out and make a few pennies.

A long time passes before he can get back on the road. He enters Libya, in that extremely dangerous and often deadly far west that is the maze of trails that lead north, at the mercy of ruthless local traffickers. He is a Bengali, small and fragile, but tenacious, and he reaches the coast. He describes the Mediterranean as the dawn of his own hope, the antechamber of the last race, but as a stopover like any other, without glory, still a non-destination. He spends about a year in Libya, working wherever he finds someone who will give him a small wage – mostly as a laborer.

But this hero from de Amicis, from “Dagli Appennini alle Ande” (From the Apennines to the Andes), a non-literary but real-life version of the 21st century, is time to finally get his day. He manages to get on a boat and disembarks in Lampedusa. A minor, he is taken into care by a program for unaccompanied minors, he is taught Italian and the moral of the story, happy ending, he works today as a waiter in Rome. He has arrived there, and he says “I did it for my family, to send help from Italy to them who are in Bangladesh”.

Other screens tell other stories unfold, other intercontinental journeys undertaken without a penny and amidst a thousand dangers. One is a micro-journey that takes place within a radius of a few kilometers. But it is the most impressive in terms of continuous changes of direction, obstacles encountered everywhere, almost meter after meter, the absurd ratio between distance covered and time spent: this is what, every day, a Palestinian from the West Bank has to face to go from one village to another, between roads reserved for Israeli settlers, checkpoints, concrete obstructions on the road, soldiers with David’s stable who unexpectedly interrupt the route, and so on. He never got discouraged and stays on the road.

This year’s Biennale is worth it just to sit at the Arsenale and follow these heroes of our time, step by step.

We realize that these migrants are the “modern”, avant-garde, more up-to-date than us: cosmopolitan, capable of finding their way through a thousand difficulties, of getting to grips with languages, of dominating the global world. No master’s degree in the best of universities can prepare them to face the life of the century as they have learned.

The recording of their voices, the idea of showing us only a marker and a map that barely takes the form of a roadmap, are by Bouchra Khalili, a French-Moroccan artist living in Vienna. A Mediterranean, an Arab, a European. And yet, The Mapping Journey Project was funded by the Museom of Modern Art in New York, in America, not by the European Union or one of the many Arab foundations, when instead it should be shown in every school or in every parliament in Europe. But watching these videos is like looking in the mirror – and we don’t like it.