“Unstoppable”, una canzone che è un viaggio e una variazione sul tema, ognuna col suo riscatto

"Unstoppable", una canzone in due versioni, ognuna con la sua storia, ciascuna con uno stile completamente diverso.

"Unstoppable", una canzone in due versioni, ognuna con la sua storia, ciascuna con uno stile completamente diverso.

(English translation below)

Gli Archivi Storici dell’UE mi hanno invitato a parlare delle sfide europee con una formula innovativa: nel corso del mio discorso avrei dovuto presentare un oggetto (di cui ho già scritto) e un brano musicale che abbia un suo significato per i cambiamenti della nostra società. Se per l’oggetto, ho optato per la straordinaria storia, privata e collettiva, della Vespa, nello sterminato universo musicale mi sono inizialmente orientato su “Bella ciao” – nelle sue versioni tradizionale, in quella discussa ucraina, o nel capolavoro di Goran Bregovic, e tante altre, poi su Bread & Rozes, magari in quel gioiellino sconosciuto russo, e anche su Bach e la sua Offerta musicale, intreccio matematico di specchi rovesciati, gioco tra un potente monarca e un genio dalla vita personale sobria.

Ognuno potrebbe pensare a questa musica che ha espresso il cambiamento e arrivare alla sua conclusione – è un esercizio stimolante. Agli Archivi UE, un conferenziere prima di me aveva ad esempio presentato un pezzo pianistico romantico, adducendolo a esempio di musica che usciva dalle corti ed entrava nelle case borghese, primo passo della democratizzazione della musica colta: pensare attraverso la musica che ha interpretato le nostre società, è un viaggio inesauribile.

Con la mia lezione, negli Archivi Storici dell’UE ha alla fine fatto irruzione il ritmo vorticoso di un Unstoppable in due salse. Abbiamo ascoltato prima la versione madre di Sia, che illustra un punto di non ritorno nella narrazione della donna ferita. Il riscatto non ha nulla di mieloso e pseudo-romantico, ma è un testo di parole assertive, tutte forza e volontà: nessuno mi può fermare, ho le batterie cariche, ho indossato l’armatura.

Questa donna si pone al centro, e non come oggetto di desiderio, non all’attenzione del suo uomo, ma come una guerriera che si fa valere urbis et orbis. Sia, che ha avuto i suoi dolori, in questa canzone ha stracciato gli stereotipi, e le centinaia di milioni di visualizzazioni del suo brano dimostrano che era tempo che qualcuno lo facesse.

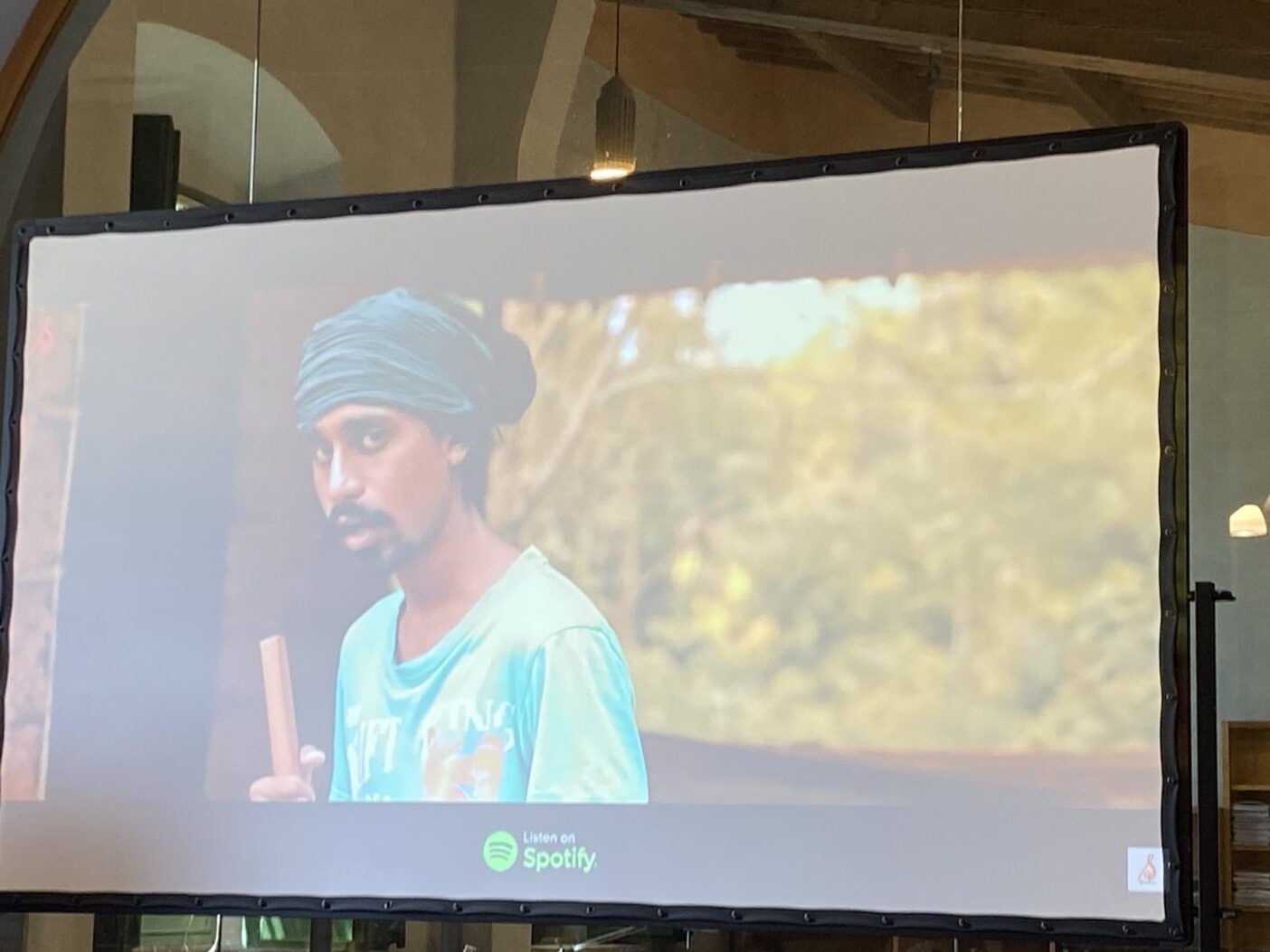

Fin qui tutto bene. Ma chi mi ascoltava è rimasto sconcertato dal secondo brano che ho presentato: sempre Unstoppable, ma in una versione come rovesciata. Ci troviamo in un villaggio dell’Asia meridionale – Sandaru Sathsara, il geniale interprete youtuber di questa cover, è uno srilankese che vive in Australia, e col suo scopino in mano ci porta in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, e canta a nome di tutti.

Altro che Sia: non c’è alcun palcoscenico tecnologico, nessun effetto luce, siamo davanti a una dimessa abitazione; la voce non ha nulla di potente e tantomeno la tenuta del cantante. Eppure le parole sono le stesse, e l’effetto è dirompente: nessuno può fermare questo giovane contadino asiatico che non ha paura di niente, che guarda in faccia il mondo con la una timidezza tenace. Ha uno sguardo radicalmente opposto a quello di Sia, ma a suo modo con la stessa determinazione. Sarà pure, per alcuni, una caricatura dell’originale, ma io conosco bene quel modo di guardare, quel modo di parlare: la testardaggine di chi sa che il futuro è proprio di queste folle di giovani del sud che si fanno avanti sulla scena del mondo, e se lo prendono. Nessuno li può fermare, stanno arrivando, anche loro hanno le batterie cariche.

Strano cammino quello di Unstoppable: davvero questa canzone non si è fermata. Dall’Australia, dove è nata Sia, è passata in Europa (Sia vive a Londra, e quest’anno si è risposata in Italia), mentre il suo mentore viene dallo Sri Lanka, ma è emigrato in Australia. Entrambi sono seguiti in tutto il mondo e quest’anno sono stati ascoltati anche agli Archivi dell’Unione Europea, sulle colline di Firenze. Ciascuno con uno stile completamente diverso dall’altro, hanno cantato di un mondo che cambia, viaggiando con una musica che pur essendo la stessa, va in direzioni diverse. Ma sempre avanti.

ENGLISH VERSION

Unstoppable – a song that is a journey and variation on the theme, each with its own redemption

The EU Historical Archives invited me to talk about European challenges with an innovative formula: during my speech I was asked to present an object (on which I have already written about ) and a piece of music that has its own significance for the changes in our society. If for the object, I opted for the extraordinary private and collective history of the Vespa, in the endless universe of music, I oriented myself on “Bella ciao” – in its traditional versions, in the controversial Ukrainian one, in Goran Bregovic’s masterpiece, and many others, then on “Bread & Rozes”, perhaps in that unknown Russian gem, and also on Bach and his “Musical Offering”, a mathematical interweaving of inverted mirrors, a game between a powerful monarch and a genius with a sober personal life.

Everyone could think about this music that is an “expression of changes” and come to its conclusion – it is an inspiring exercise. At the EU Archives, a lecturer before me had, for example, presented a romantic piano piece, citing it as a piece of music that left the courts and entered bourgeois homes, the first step in the democratization of classical music: thinking through the music that interpreted our society, it is an inexhaustible journey.

With my lesson, the dizzying rhythm of a two-pronged “Unstoppable” versions finally broke into the Historical Archives of the EU. We first heard Sia’s original version, that illustrates a point of no return in the wounded woman’s narrative. The ransom has nothing honeyed or pseudo-romantic about it, but is a text of assertive words, all strength and will: no one can stop me, my batteries are charged, I’ve worn the armor.

This woman places herself at the center, and not as an object of desire, not to the attention of her man, but as a warrior who asserts herself urbis et orbis. Sia, who had her misadventures, tore up stereotypes in this song, and the hundreds of millions of views of her song prove that it was time someone did it.

So far, so good. Yet, even more attention got the second song I presented: once more “Unstoppable”, but in a reversed version. We are in a village in South Asia – Sandaru Sathsara, the brilliant YouTuber interpreter of this cover, is a Sri Lankan who lives in Australia, and handling his brush he takes us to Bangladesh, India, Pakistan – he sings on behalf of all of them.

We are far from the Sia set: there is no technological stage, no light effect, we are in front of a shabby house; the voice has nothing powerful and even less the singer’s appearance.

However, the words are the same, and the effect is disruptive: no one can stop this young Asian farmer who is not afraid of anything, who looks the world in the face with tenacious shyness.

He has a radically opposite look to Sia’s, but he goes trough his way with the same determination. For some, it may well be a caricature of the original, but I know well that way of looking, that way of speaking: the stubbornness of those who know that the future belongs precisely to these “crowds” of young people from the South who come forward on the world scene, and they take it. Nobody can stop them, they are coming, they too have fully “charged batteries”.

Unstoppable’s journey is strange: this song really “didn’t stop”. From Australia, where Sia was born, it moved to Europe (Sia lives in London, and this year she remarried in Italy), while her mentor is from Sri Lanka and emigrated to Australia.

Both have followers all over the world and this year they were also heard at the Archives of the European Union, on the hills of Florence. With each a completely different style from the other, they sang about a changing world, travelled with a music that, despite being the same, goes in different directions. But always forward.