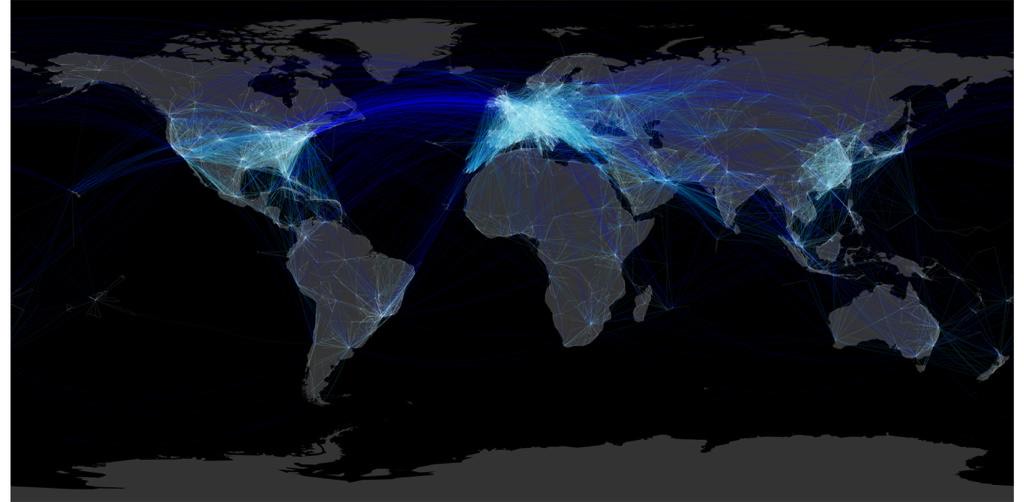

Il sito Invisible Data per capire l’illogica realtà delle lunghe nuove rotte aeree per non sorvolare la Russia

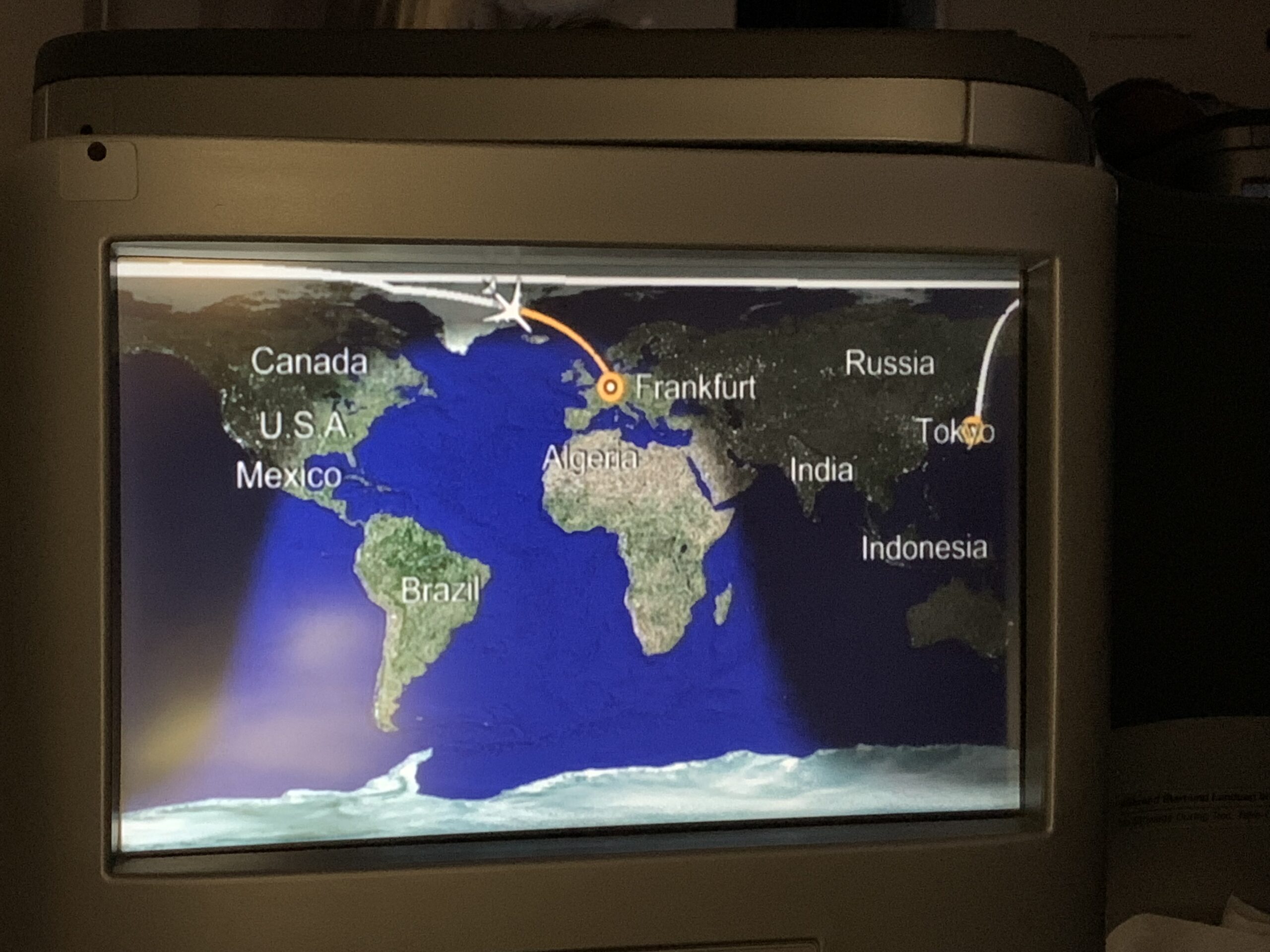

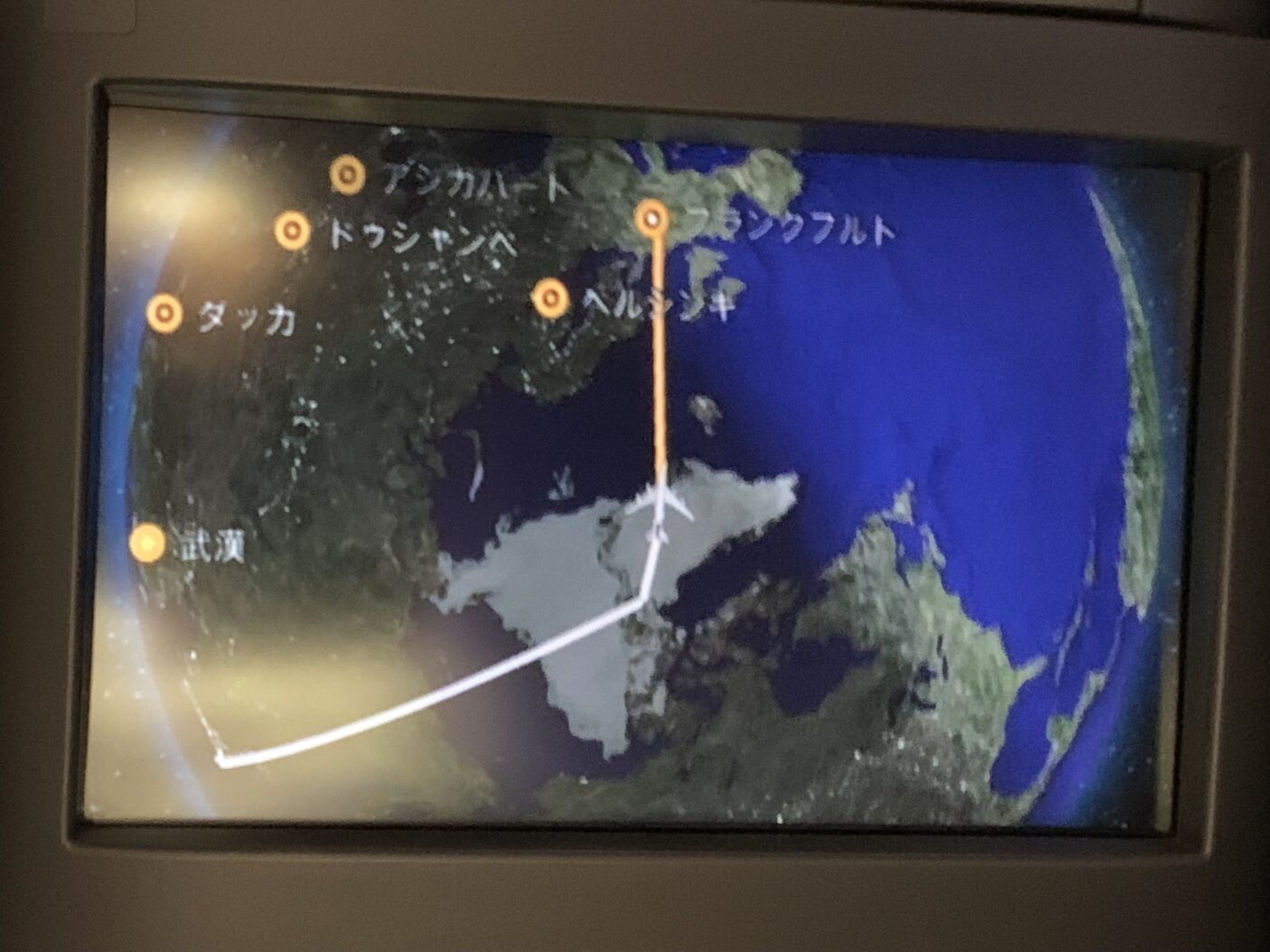

La guerra in Ucraina crea nuove infinite rotte aeree che arrivano in cima al mondo per poi virare, evitando così la Russia. E' il riflesso della guerra dalla terra al cielo.