La Vespa, quando due ruote cambiano l’Europa. Un museo a Pontedera

Vedere diversamente un motociclo e inventare un’icona della nostra vita. La Vespa, la sua storia, simbolo anche di emancipazione femminile.

Vedere diversamente un motociclo e inventare un’icona della nostra vita. La Vespa, la sua storia, simbolo anche di emancipazione femminile.

(English translation below)

Gli Archivi Storici dell’Unione Europea mi hanno invitato a parlare a studenti e ricercatori su un tema canonico (il processo di integrazione comunitaria) ma con un approccio diverso dal solito: nel corso della mia presentazione avrei dovuto raccontare di una musica (ne scriverò successivamente) e di un oggetto che sia per la società europea che per la mia vicenda personale, ha rappresentato un’occasione di crescita – con vasto margine di interpretazione personale: crescita civile, economica, morale, intima.

Ci ho pensato un po’, e ho considerato alcuni libri fondamentali, una bomboniera sopravvissuta futura memoria alla coppia che dopo il matrimonio fu deportata ad Auschwitz per il loro viaggio di nozze, o anche la mia piccozza da alpinista che sulle Alpi o nel mondo mi ha portato in territori di roccia e ghiaccio privi di frontiere statali. Mica facile scegliere, perché come il metodo archivistico insegna, vi sono veramente oggetti che viaggiano e hanno fatto la Storia, e ognuno di noi li conserva gelosamente, anche se poi magari se li dimentica in qualche cassetto.

Alla fine ho proposto un’icona dell’Italia del dopoguerra, e anche della mia adolescenza: la Vespa. Un oggetto un po’ ingombrante da proporre durante una conferenza, ma, complice il mese di giugno, ho ottenuto di poter portare la mia Vespa fino a davanti all’ingresso di Villa Salviati, sede degli Archivi, in modo che i partecipanti potessero uscire al momento opportuno a osservare dal vivo perché questo motociclo ha favorito alcuni cambiamenti della nostra società.

Su Netflix, si trova un film che evoca bene alcuni di questi aspetti. La Piaggio era soprattutto un’azienda di aerei e camion militari, la cui fabbrica di Pontedera fu ampiamente danneggiata dai bombardamenti alleati. Dopo la guerra restavano la ditta, le maestranze, il savoir-faire, ma nessuno in Italia aveva più bisogni di aerei militari. Altri erano i bisogni, e in primis, rilanciare l’economia di una società da ricostruire. E con i precoci segni di un’urbanizzazione che sarebbe divenuta presto massiccia. La mobilità dei lavoratori era quello che richiedeva delle nuove soluzioni, e alla Piaggio si pensò di investire non nelle più costose automobili, ma in motocicli alla portata di tutti. L’industria militare si converte a produzione di pace.

I magazzini aziendali conservavano un notevole numero di ruote per aerei militari ancora da costruire. Nell’Italia delle ristrettezze dell’immediato dopoguerra niente poteva essere buttato via, e queste ruote più piccole di quelle normalmente usate per le motociclette, furono il punto di partenza di uno scooter che non poteva che essere diverso dagli altri. Si afferma un primo progetto industriale di riciclo.

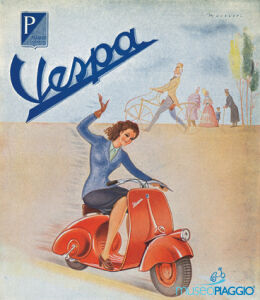

L’Italia esce dalla guerra con una profonda trasformazione: molti uomini sono scomparsi in guerra, le donne sono chiamate alla ricostruzione del paese, votano per la prima volta al referendum del 1946, occupano rapidamente un ruolo crescente non solo nella famiglia ma anche nel lavoro. Anche le donne hanno un problema di mobilità, ma hanno a disposizione solo i mezzi pubblici, le rarissime automobili, o la bicicletta. Ancora non avvezze al pantalone, non possono guidare a cavalcioni una motocicletta. A meno di non inventarne una di nuova concezione che non abbia una forma inedita che permetta di tenere le gambe coperte. In questo modo, anziché doversi accomodare seduta di sbieco dietro al guidatore, la donna diventa pilota autonoma, restando in gonna. Il design si fa fattore di emancipazione.

L’Italia si ritrova intorno alla famiglia, è un’Italia povera ma che comincia alcuni riti consumistici – tra i quali le gite fuoriporta. Anche senza automobile, io lungo sedile di una Vespa ha permesso di accomodare anche due adulti e, davanti al manubrio, un bambino. La ruota di scorta, a lungo parte della dotazione di serie, costituiva una protezione in strade sterrate. La Vespa è una risposta alle nuove esigenze della famiglia.

La sua forma singolare e il modo diverso di guidarla – quasi a metà strada con una automobile, con tanto di pedali – si presta a mille variazioni sul tema. Vespe in versione professionali e perfino militari – la soluzione polivalente.

Nata durante la trasformazione dell’Italia e dell’Europa, la Vespa è sopravvissuta fino a oggi perché le sue innovazioni sono restate d’attualità, e così è stata adottata o imitata nel Sud e nel Sud-Est asiatico. Dalle proprie fabbriche in Vietnam, Piaggio esporta in tutta la regione – una risposta ai problemi dell’Italia che diventa globale.

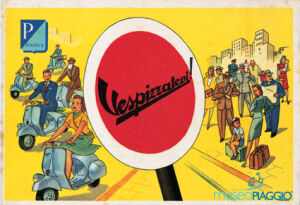

Vespa è uno strano nome, e da subito la comunicazione è stata diversa dal solito. Il rumore del suo motore ricorda quello di un insetto libero e imprevedibile? Un omaggio al volare a zonzo, senza limiti e mete prefissate? E bastò una campagna pubblicitaria con uno slogan d’avanguardia – Chi Vespa mangia le mele – per rilanciare in una gioventù irrequieta un prodotto che continuava a richiamare nuove trasgressioni dell’intera Europa – con una giovinezza alle prese col frutto proibito.

Oggetto di un inesauribile produzione libraria, usata per mitici viaggi, e protagonista di un museo che vale da solo la visita a Pontedera. La Vespa è un feticcio di artisti, creatori, un bene comune da conservare.

Io ho umilmente portato questo manufatto industriale e fiabesco, ormai vecchio di settanta anni e sempre nuovissimo, reincarnatosi in mille vite, nel cuore della memoria dell’Europa. E anche più dell’accoglienza che gli Archivi Storici dell’UE hanno riservato a questa provocazione, la piccola ma vera consacrazione della Vespa è stato che una volta di più, alla fine della conferenza, mi ha riportato a casa.

ENGLISH VERSION

Conceiving a motorcycle differently and inventing an icon of our life

The Historical Archives of the European Union invited me to speak to students and researchers on a canonical theme (the process of the European integration) but with an usual approach: during my presentation I should have told about a song (I’ll come back in another article about that) and n object that is for European society which, for my personal story, represented an opportunity for growth – with vast margin for personal interpretation: civil, economic, moral, intimate growth.

I thought about it a bit, and I considered some fundamental books, a wedding present that survived as a future memory of the couple who right after marrying was deported to Auschwitz for their honeymoon, or even my mountaineer’s ice ax that in the Alps or in the world took me to territories of rock and ice without state borders.

It’s not easy to choose, because as the archival method teaches, there are truly objects that travel and have made history, and each of us jealously preserves them, even if we then perhaps forget them in some drawer. In the end I proposed an icon of post-war Italy, and also of my adolescence: the Vespa. A somewhat cumbersome object to propose during a conference, but, thanks to the month of June, I was able to take my Vespa up to the entrance of Villa Salviati, home of the Archives, so that the participants could go out to opportune moment to observe first hand why this motorcycle has favored some changes in our society.

On Netflix, there is a film that evokes some of these aspects well: Piaggio was above all a military aircraft and truck company, whose Pontedera factory was extensively damaged by Allied bombing. After the war, the company, the workers, the savoir-faire remained, but no one in Italy anymore needed military aircrafts. There were other needs, and first and foremost, to relaunch the economy of a society in need of reconstruction. And with the early signs of an urbanization that would soon become massive. The mobility of workers required new solutions, and Piaggio decided to invest not in the most expensive cars, but in motorcycles, affordable for many more. The military industry is converted to peace production.

The company warehouses stored a significant number of wheels for military aircraft still to be built. In the restrictive Italy of the immediate post-war period, nothing could be thrown away, and these wheels, smaller than those normally used for motorcycles, were the starting point for a scooter that had to be different from the others. A first industrial recycling project is established.

Italy emerged from the war with a profound transformation: many men disappeared in the war, women were called to rebuild the country, they voted for the first time in the 1946 referendum, they rapidly occupied a growing role not only in the family but also in work. Women had a mobility problem, they only had access to public transport, to the rare cars, or to the bicycles. Still not used to wearing trousers, they could not ride a motorcycle. Unless Piaggio invented a new concept of motorbike that allowed to keep legs protected. In this way, instead of having to sit sideways behind the driver, the woman became an autonomous driver, remaining in a skirt. Design becomes a factor of emancipation.

Italy finds itself around the family, it is a poor Italy but one that begins some consumerist rituals – including trips out of town. Even without a car, the long seat of a Vespa made it possible to seat two adults and, in front of the handlebars, a child. The spare wheel, long part of the standard equipment, provided protection on dirt roads. The Vespa is a response to the new needs of the family.

Its singular shape and the different way of driving it – almost halfway with a car, complete with pedals – lends itself to a thousand variations on the theme. Vespa has several professional and even military versions: the multipurpose solution.

Born during the transformation of Italy and Europe, the Vespa has survived to this day because its innovations have remained relevant, and so it has been adopted or imitated in South and South-East Asia. From its factories in Vietnam, Piaggio exports throughout the region – a response to the problems of Italy going global.

Wasp is a strange name, and from the start the communication was different than usual. Does the noise of his engine resemble that of a free and unpredictable insect? A tribute to flying loosely, without limits and pre-established destinations? And an advertising campaign with an avant-garde slogan – Who Wasp eats apples – was enough to relaunch a product in a restless youth that continued to recall new transgressions of the whole of Europe – a youth and the prohibited fruit.

Object of an inexhaustible book production, used for legendary journeys, and the protagonist of a museum that alone is worth the visit to Pontedera. The Vespa is a fetish of artists, creators, a common good to be preserved.

I have humbly brought this industrial and fairy-tale artefact, now seventy years old and always brand new, reincarnated in a thousand lives, into the heart of Europe’s memory. And even more than the welcome that the EU Historical Archives gave to this provocation, the small but true consecration of the Vespa was that once again, at the end of the conference, it brought me home.