Ma che ci fa la poppa di una nave in una chiesa? Riscoprire Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia e i suoi piccoli gioielli nascosti: la Chiesa dell'Orazione e della Morte nasconde un gioiello della marina pontificia.

(English translation below)

Ci sono delle città che spesso vengono considerate solo crocevia, luoghi di snodo di itinerari di viaggio, punti di transito per chi va e chi torna, luoghi che in ogni caso non meritano una sosta. Ad esempio Orte, Chiusi, Civitavecchia, uscite autostradali o porti di sbarco che sono percepiti solo come stazioni di passaggio lungo un viaggio che non è concluso, che terminerà altrove.

Luoghi che non riescono ad attrarre l’occhio curioso, perché il viaggiatore li attraversa distratto, concentrato solo sul suo itinerario da portare a termine.

Civitavecchia è sempre stata considerata il porto di Roma: distante solo ottanta chilometri dalla capitale, è uno dei luoghi di arrivo per gli stranieri che entrano in Italia con le navi da crociera. E dunque chi vi sbarca la attraversa solo per raggiungere la stazione ferroviaria in direzione della capitale, oppure per salire sul bus turistico che lo porterà al Gianicolo o a San Pietro.

Eppure come dice il nome stesso, Civitavecchia è città antichissima, fondata dagli Etruschi e resa quello che è oggi dall’imperatore Traiano, che la volle attrezzare con un grande porto disegnato dall’architetto arabo-siriano Apollodoro di Damasco. Un porto che se un tempo era il principale snodo commerciale e marittimo del Mediterraneo, ancora oggi compete con Barcellona per il primato di primo porto croceristico europeo.

E nonostante gli oltre settanta bombardamenti che durante la seconda guerra mondiale la danneggiarono irrimediabilmente, e che le sono valsi una medaglia al valor militare, ancora conserva qualche perla di prezioso passato da ammirare.

E tra queste rare perle di bellezza artistica, ce n’è una che vi sorprenderà, custodita nel gioiello architettonico più pregevole di Civitavecchia, la chiesa di Santa Maria dell’Orazione, chiamata della morte perché vi risiedeva la Confraternita della Morte, che si occupava di dare degna sepoltura a coloro che morivano per strada o in mare senza che nessun familiare andasse a recuperarlo.

Qui il senso della morte è impresso nella stessa architettura della chiesa, risalente al barocco del XVII secolo: la volta infatti, dipinta dal Cavaliere Giuseppe Errante da Trapani, è di forma ellittica per ricordare la forma ovale del teschio umano.

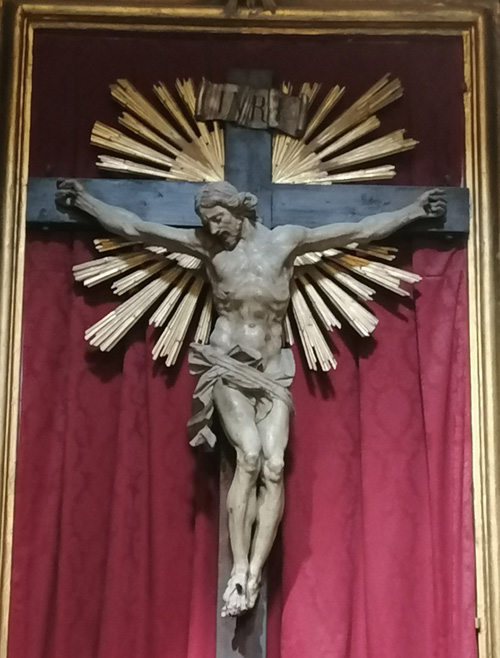

E la sua stessa struttura architettonica è inusuale, perché non solo è a croce greca, ma vi si aprono ben sette cappelle. Quella centrale è decorata da una bellissima pala d’altare, dipinta dallo stesso autore della volta, rappresentante l’assunzione della Vergine Maria tra le anime del Purgatorio, poi alle estremità dell’altro braccio della croce si aprono altre due cappelle, delle quali quella sinistra custodisce un prezioso crocifisso ligneo dal particolare fascino, in cui l’armonia anatomica del corpo del Cristo raggiunge rari livelli di perfezione artistica.

Ma poi la struttura si snoda attraverso quattro porte che conducono ad altre quattro cappelle: due sono destinate alla sacrestia e agli uffici parrocchiali, mentre le altre sono altrettanti piccoli gioielli di arte pittorica e scultorea. A destra si apre la decoratissima cappella Guglielmini, dedicata alla Beata Vergine dei Sette Dolori, mentre l’altra è dedicata a San Michele Arcangelo, con la bellissima statua lignea policroma del santo.

Ma il piccolo capolavoro artistico e storico che più mi conquista ogni volta che entro in questa chiesa è la balaustra lignea policroma che protegge l’organo sulla parete in controfacciata. Si tratta di una balaustra ricavata dalla poppa di una antica nave, la galera San Pietro. Nel XVI secolo questa era la nave ammiraglia dello Stato Pontificio, e partecipò alla battaglia di Lepanto del 1571, vinta dalle forze cristiane della Lega Santa contro le flotte musulmane dell’Impero Ottomano.

La poppa si presenta come una balaustra modanata in morbide curve, dipinta in verde e azzurro, decorata con spire, volute, fiori e putti in oro e sormontata dallo stemma della Chiesa con le chiavi incrociate e la mitra episcopale. In alto campeggia poi un altro stemma con un teschio, simbolo della Confraternita della Morte.

La galera San Pietro era una nave a doppia propulsione, cioè poteva andare a vela e a remi, ed era molto manovriera. Era la nave più importante della marina pontificia, e faceva base a Civitavecchia, dove c’era l’arsenale dello Stato Pontificio.

La sola idea che quella balaustra abbia potuto solcare i mari in un tempo così remoto, mantenendo tutta la sua regale bellezza, racconta tanto della abilità dei carpentieri di quei secoli antichi, capaci di realizzare imbarcazioni non solo indistruttibili, ma anche impreziosite da raffinati decori.

Il piccolo gioiello architettonico della Chiesa di Santa Maria della Morte, con la splendida poppa della galera San Pietro, vale già da solo una permanenza in città, perché la sua architettura, espressione del più raffinato barocco, e le preziose opere d’arte che custodisce, regalano emozioni in grado di riscrivere la storia di Civitavecchia, troppo facilmente cancellata dai bombardamenti dell’ultima guerra.

Ma a Civitavecchia c’è un altro manufatto che ci aiuta a comprendere la grande maestria dei carpentieri del passato nell’ingegneria marittima: è una liburna, una nave romana di cui è stata fatta una fedele ricostruzione. La liburna era una bireme leggera, con 25 rematori disposti su due file per ciascuna fiancata, per un totale di cento rematori.

La nave, di cui è stato riprodotto a grandezza naturale un solo segmento, è opera delle ricerche del laboratorio di archeologia sperimentale CANS LANS, l’unico laboratorio italiano che da anni studia le antiche tecniche edificatorie nella marineria romana, diretto dal comandante Mario Palmieri, che collabora con il corso di Archeologia subacquea dell’Università agli studi Roma 3.

La straordinarietà dell’opera è che è stata riprodotta utilizzando esclusivamente le tecniche costruttive e le tecnologie dell’epoca.

L’esperimento ha messo in luce che la tecnica costruttiva delle carpenterie romane era molto più complessa ed evoluta rispetto a quella oggi in uso per la costruzione delle moderne imbarcazioni in legno.

Un esperimento che dimostra l’elevato livello di abilità della potente corporazione dei fabri navales, veri e propri architetti che, con tecniche sofisticate ed innovative, hanno posto le basi della moderna ingegneria navale.

ENGLISH VERSION

There are cities that are often considered only crossroads, hubs of travel itineraries, transit points for those who go and those who return, places that in any case do not deserve a stop. For example, Orte, Chiusi, Civitavecchia, just motorway exits or ports of disembarkation that are perceived only as way stations along a journey that has not ended, which will end elsewhere.

Places that fail to attract the curious eye, because the traveler crosses them distracted, concentrated only on his itinerary to complete.

Civitavecchia has always been considered the port of Rome: only eighty kilometers away from the capital, it is one of the arrival points for foreigners entering Italy on cruise ships. And therefore those who disembark there only cross it to reach the railway station in the direction of the capital, or to get on the tourist bus that will take them to the Gianicolo or San Pietro.

Yet as the name itself says, Civitavecchia is an extremely ancient city, founded by the Etruscans and made what it is today by the emperor Trajan, who wanted to equip it with a large port designed by the Arab-Syrian architect Apollodorus of Damascus. A port that, if was once the main commercial and maritime hub of the Mediterranean, still today competes with Barcelona for the primacy of the first European cruise port.

And despite the more than seventy bombings that damaged it irreparably during the Second World War, and which earned it a medal for military value, it still retains some pearls of its precious past to admire.

And among these rare pearls of artistic beauty, there is one that will surprise you, kept in the most valuable architectural jewel of Civitavecchia, the church of Santa Maria dell’Orazione, called the church of death because the Brotherhood of Death resided there, to give a proper burial to those who died on the road or at sea without any family member going to retrieve it.

Here the sense of death is imprinted in the very architecture of the church, dating back to the 17th century Baroque: in fact, the vault, painted by Cavaliere Giuseppe Errante from Trapani, is elliptical in shape to recall the oval shape of the human skull.

And its architectural structure itself is unusual, because not only is it in the shape of a Greek cross, but seven chapels open onto it. The central one is decorated with a beautiful altarpiece, painted by the same author of the vault, representing the assumption of the Virgin Mary among the souls in Purgatory, then at the ends of the other arm of the cross there are two other chapels, of which the left holds a precious wooden crucifix with a particular charm, in which the anatomical harmony of the body of Christ reaches rare levels of artistic perfection.

But then the structure winds through four doors that lead to another four chapels: two are intended for the sacristy and parish offices, while the others are as many small jewels of pictorial and sculptural art. To the right is the highly decorated Guglielmini chapel, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin of the Seven Sorrows, while the other is dedicated to the Archangel Michael, with the beautiful polychrome wooden statue of the saint.

But the small artistic and historical masterpiece that conquers me the most every time I enter this church is the polychrome wooden balustrade that protects the organ on the counter-façade wall. It is a balustrade obtained from the stern of an ancient ship, the San Pietro ship. In the 16th century, this was the flagship of the Papal States and participated in the battle of Lepanto in 1571, won by the Christian forces of the Holy League against the Muslim fleets of the Ottoman Empire.

The stern looks like a balustrade molded in soft curves, painted in green and blue, decorated with coils, volutes, flowers, and cherubs in gold, and surmounted by the coat of arms of the Church with crossed keys and the episcopal miter. At the top stands another coat of arms with a skull, symbol of the Brotherhood of Death.

The San Pietro ship was a double propulsion ship, it could go sailing and rowing, and was very manoeuvrable. It was the most important ship of the papal navy and was based in Civitavecchia, where there was the arsenal of the Papal State.

The mere idea that that balustrade could sail the seas in such a remote time, maintaining all its regal beauty, tells a lot about the skill of the carpenters of those ancient centuries, capable of making boats that are not only indestructible but also embellished with refined decorations.

The small architectural jewel of the Church of Santa Maria della Morte, with the splendid stern of the San Pietro ship, is already worth a stay in the city, because its architecture, an expression of the most refined Baroque, and the precious works of art it houses , offer emotions capable of rewriting the history of Civitavecchia, too easily erased by the bombings of the last war.

But in Civitavecchia there is another artifact that helps us understand the great mastery of the carpenters of the past in maritime engineering: it is a liburnian, a Roman ship of which a faithful reconstruction has been made. The liburnian was a light bireme, with 25 oarsmen arranged in two rows on each side, for a total of one hundred oarsmen.

The ship, of which only one segment has been reproduced in full size, is the work of research by the CANS LANS experimental archeology laboratory, the only Italian laboratory that has been studying ancient building techniques in the Roman navy for years, directed by the commander Mario Palmieri, which collaborates with the Underwater Archeology course of the University of Rome 3.

The extraordinary nature of the work is that it was reproduced using only the construction techniques and technologies of the time.

The experiment has highlighted that the construction technique of Roman carpentry was much more complex and evolved than that used today for the construction of modern wooden boats.

An experiment that demonstrates the high level of skill of the powerful corporation of naval locksmiths, real architects who, with sophisticated and innovative techniques, laid the foundations of modern naval engineering.

2 Commenti

Peccato che da un po’ è chiusa per lavori

La chiesa della Confraternita della Morte ha riaperto già da tempo, ed è visitabile tutte le mattine.