Gli zoo umani: in Belgio la mostra sulle esposizioni coloniali di africani in gabbia

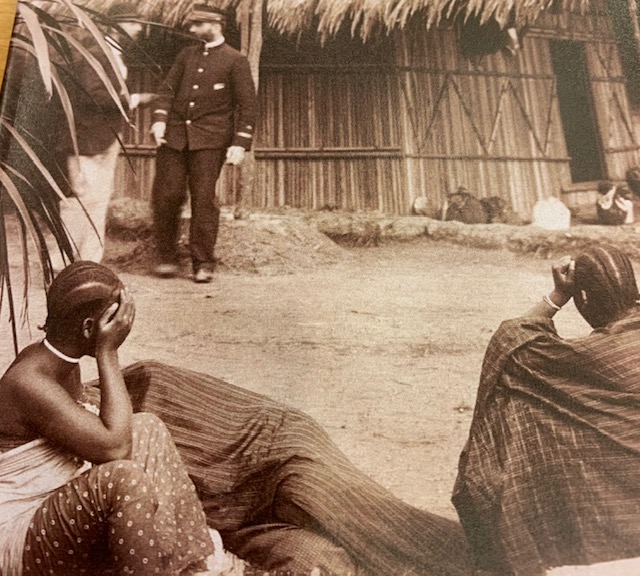

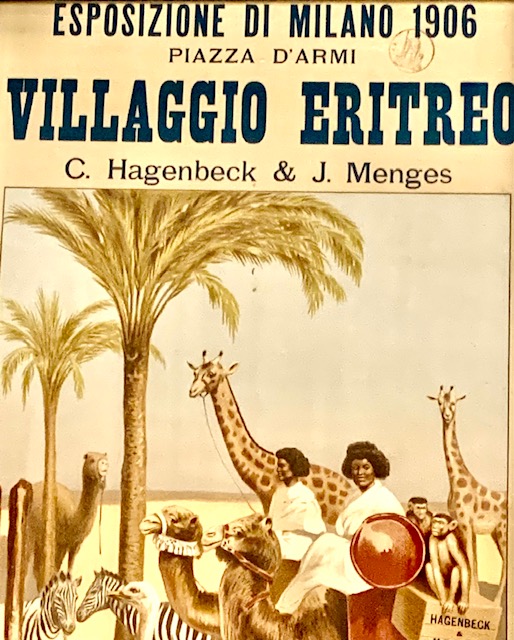

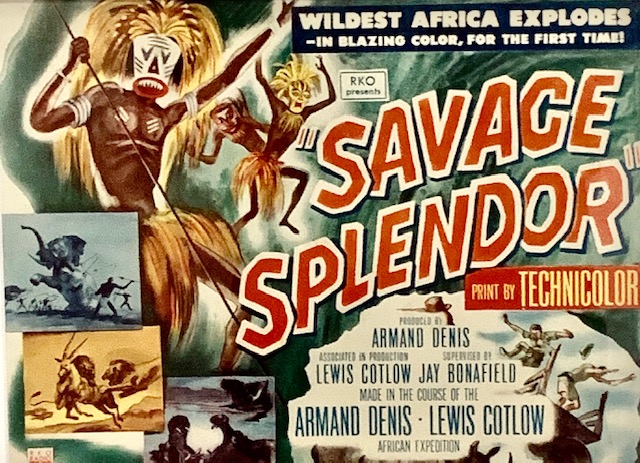

A Tervuren fino al 6 marzo la mostra che racconta "l'altro" come oggetto di divertimento o interesse scientifico. Documenti eccezionali sulle esposizioni di africani in gabbia, in alcuni casi immagini mostrate per la prima volta al pubblico.