Non i muri di Orbán per la presidenza ungherese dell’UE, ma il viaggiare di Sandor Márai

Salutiamo la presidenza dell'Ungheria dell’UE, con il viaggiare di Sandor Márai e i suoi libri da leggere per guardare oltre i muri

Salutiamo la presidenza dell'Ungheria dell’UE, con il viaggiare di Sandor Márai e i suoi libri da leggere per guardare oltre i muri

English translation below

Salutiamo la presidenza ungherese dell’Unione Europea e il suo – chiamiamolo così, con la nostra indulgenza – enfant terrible Orbán, ricordando, in forma di protesta, che Ungheria è ben altro che lo scempio politico di questi anni.

In Europa, gli ungheresi hanno un rapporto col viaggio come pochi altri: se io sono italiano, toscano, fiorentino, ed etrusco, con una continuità che conoscono molti europei tra l’oggi e la stanzialità di millenni, i geni degli ungheresi sono arrivati da molto lontano, proveniente dai magiari, dal nomadismo, dalle steppe dell’Asia Centrale. Si sono portati dietro una lingua incomprensibile, dove perfino la parola pressoché universale cinema è mozi.

Poi, come capita in questi casi, una volta installatisi nel cuore dell’Europa, nel cuore della Mitteleuropa, ne sono diventati i guardiani. Hanno fermato i mongoli prima e poi gli ottomani, per primi si ribellarono ai carri armati sovietici. Orbán si è messo in testa di fermare anche ciò che considera le presenti reincarnazioni di tali minacce – migranti e in particolare musulmani, ma anche le idee dei nuovi diritti civili e perfino i senza fissa dimora, costruendo mura mentali, politiche e anche fisiche. Salvo poi sbracare il paese aprendolo a ogni tipo di investimento cinese (l’Ungheria riceve il 44% degli investimenti di Pechino in tutta Europa) – cosa ben più grave e strutturale in termini si cessione di sovranità effettiva e di invasione.

Che frattura rispetto ad altri ungheresi, che vedevano i movimenti tra popoli diversamente: viaggiare per incontrare, per cultura, per libertà. Tra questi, un feticcio del lettore italiano: Sandor Márai, che in Italia ha vissuto a lungo senza essere conosciuto, che è stato scoperto postumo con decine di ristampe dei suoi volumi e che amava Firenze e il sud: Questo era il suo giudizio su Napoli:

“una delle ultime in cui la parola civilitas possieda ancora un significato tangibile e quotidiano”.

Márai aveva sempre viaggiato, anche a Budapest: leggeva e scriveva, reinventava le peregrinazioni di Casanova (La recita di Bolzano), i monti Tatra (La sorella), Napoli come epicentro della vita (Il sangue di San Gennaro), i Carpazi come luogo della verità (Le braci), le svolte della vita che capitano nelle soste dei viaggi (L’isola) .

Quando venne il momento di dover lasciare l’Ungheria – con l’arrivo dei sovietici dopo la guerra – con il suo sguardo laico, liberaldemocratico e cosmopolita, era pronto:

“Una cultura, o tutto ciò che in genere si definisce tale – ponti, lampioni, dipinti, sistemi monetari, versi – stava cadendo a pezzi sotto il mio sguardo. Sentivo di avere un compito urgente, volevo ancora vedere qualcosa allo “stato originari”, prima che si compisse quel cambiamento indefinibile e spaventoso. Mi misi in viaggio.”

Il suo viaggio fu Italia, Europa, Stati Uniti – luoghi che hanno marcato il suo esilio, anche de Márai è restato sempre nella sua patria natale, perché la patria dove vive uno scrittore è la lingua in cui scrive, mentre il viaggio lo ha continuamente reso fecondo, acuendo i sensi e moltiplicando le storie da rivelare attraverso la sua penna:

“l’emigrazione è una prova dura, ma al tempo stesso una sorgente di forza”.

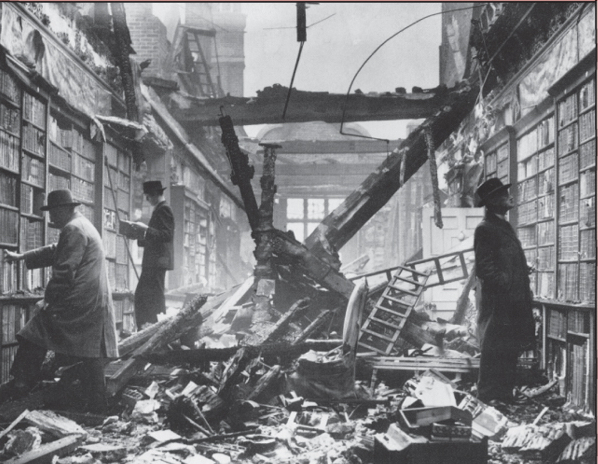

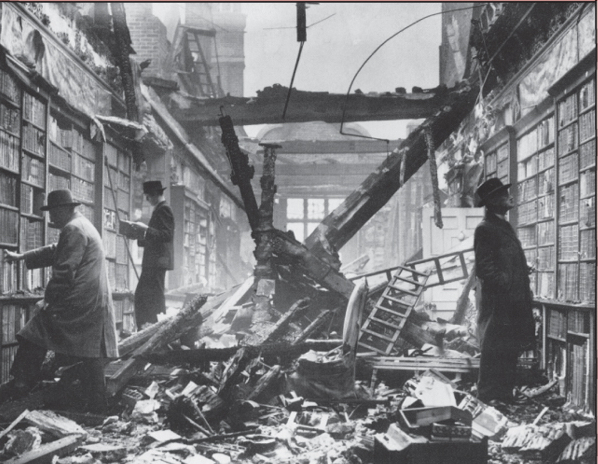

Sono queste la parole dell’Ungheria che sono rimaste, questa l’Ungheria che continuerà a cercare libri tra le macerie.

ENGLISH VERSION

Books to read to look beyond the walls of Hungary in recent years

We salute the Hungarian presidency of the European Union and its – let’s call him that, with our indulgence – enfant terrible Orbán, remembering, in the form of protest, that Hungary is much more than the political havoc of recent years. In Europe, Hungarians have a relationship with travel like few others: if I am Italian, Tuscan, Florentine, and Etruscan, with a continuity that many Europeans know between today and millennia old settling, the genes of the Hungarians came from very far away: Magyars, nomadism, steppes of Central Asia. They brought with them an amazing language, where even the almost universal word “cinema” is “mozi”. Then, as happens in these cases, once they settled in the heart of Europe, in the heart of Central Europe, they became its guardians. They stopped the Mongols first and then the Ottomans, they were the first to rebel against the Soviet tanks. Orbán has undertaken as a personal mission stopping what he considers to be the present reincarnations of these threats – migrants and in particular Muslims, but also the ideas of new civil rights and even the homeless; for all of them, he has built mental, political and even physical walls.

Yet, he has then opened the country up to every type of Chinese investment (Hungary receives 44% of Beijing’s investments throughout Europe) – which is much more serious and structural in terms of the transfer of effective sovereignty and “invasion”.

What a difference is the present scenario compared to other Hungarians, who valued migrations and travelling as a way for meeting, for culture, for freedom. Among these, a fetish of the Italian reader: Sandor Márai, who lived in Italy for a long time without being known, who was discovered posthumously with dozens of reprints of his volumes and who loved Florence and the South: This was his opinion on Naples : “one of the last in which the word civilitas still has a tangible and everyday meaning”. Who knows what the man of order Orbán would think about that.

Márai had always travelled, even in Budapest: he read and wrote, he reinvented Casanova’s wanderings, the Tatra mountains, Naples as the epicenter of life, the Carpathians as a place of truth, the turning points of life that occur during travel stops.

When the time came to leave Hungary – with the arrival of the Soviets after the war – he was ready, with his secular, liberal democratic and cosmopolitan approach: “A culture, or everything that is generally defined as such – bridges, street lamps, paintings, monetary systems, verse – it was falling apart before my gaze. I felt I had an urgent task, I still wanted to see something in its “original state”, before that indefinable and frightening change took place. I set off on my journey.”

His journey was Italy, Europe, and the United States. Place that have marked his exile. However, Márai remained in his native homeland, because the homeland where a writer lives is the language in which he writes, with the benefits of the journey that has continually made him fruitful, sharpening the senses and multiplying the stories to be revealed through his pen: “emigration is a hard test, but at the same time a source of strength”.

These are the words of the kind Hungary that have remained, that I still read; this is the Hungary that will continue to search for books in the rubble.