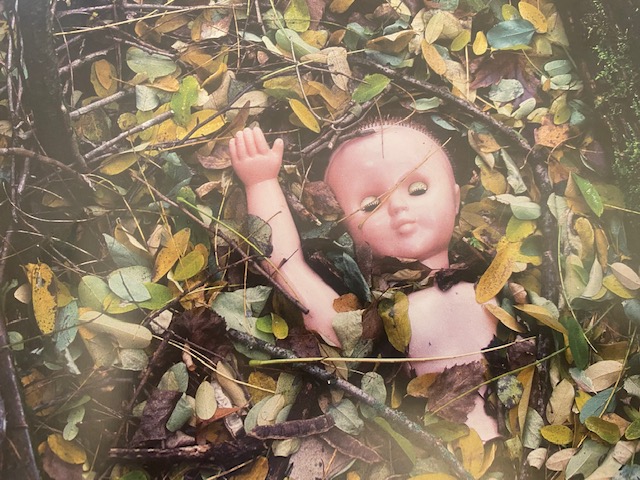

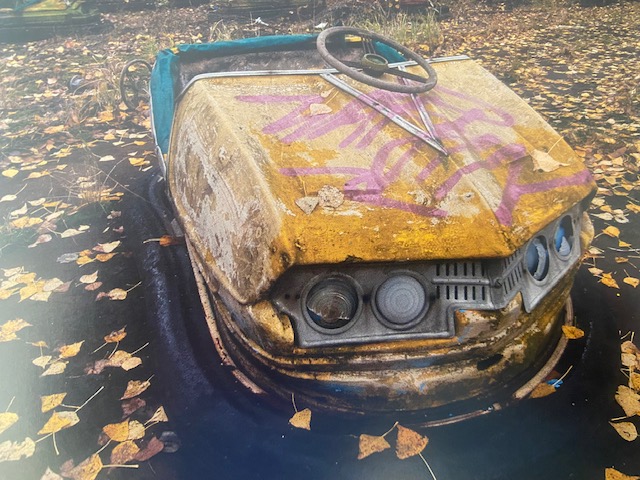

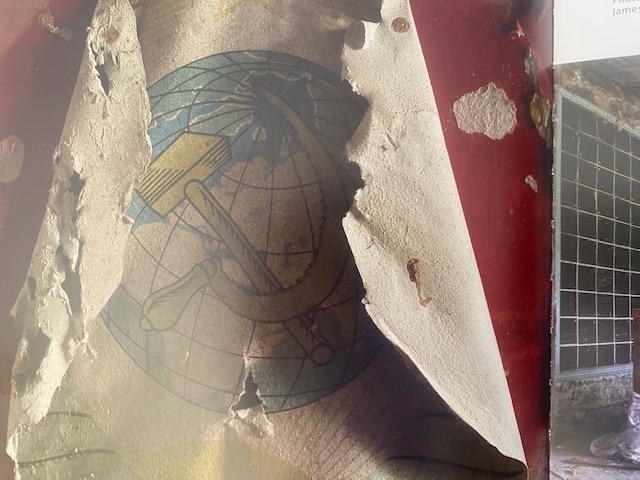

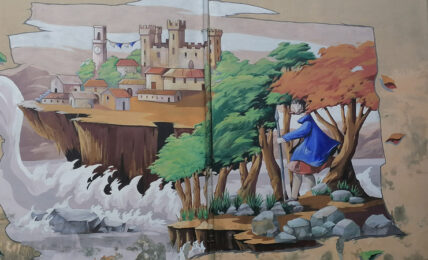

Viaggio a Chernobyl attraverso due libri su cosa accadde e cosa è restato

Chernobyl è la Pompei dell'era nucleare, segnata da una devastazione cristallizzata. Ecco le immagini spettrali e una narrazione da brividi per compiere questo viaggio vietato.