Dormire nei luoghi più improbabili, quando il sonno è il viaggio: ecco dove e come

Dormire in una scialuppa di salvataggio, o in una boa sottomarina, in un ex elicottero della guardia marina o in un tubo di cemento. Notti che valgono un viaggio.

Dormire in una scialuppa di salvataggio, o in una boa sottomarina, in un ex elicottero della guardia marina o in un tubo di cemento. Notti che valgono un viaggio.

(English translation below)

Nel 2019 mi capitò di dormire in un luogo insolito: un bivacco ad alta quota sulla parete quasi verticale del Cervino, a poco più di 4.000 metri di altezza. La Capanna Solvay avrà uno spazio di circa dieci metri quadrati e, da quanto è incastrata sulla cresta, ha la porta su un versante del Cervino e lo scarico del bagnetto sull’altro. Stipati, ci si può dormire in dieci, e solo in caso di emergenza. Io e la guida ci eravamo attardati sulla via di ritorno, per dare un mano a due cordate in difficoltà nella discesa del tratto finale della piramide sotto la vetta. Lasciatele poi alle nostre spalle, ci eravamo fermati verso le 19 a questa capanna – gli altri sarebbero arrivati quando ormai eravamo al buio, alcuni perfino a mezzanotte. Così, in un decina – tre italiani, due spagnoli, due rumeni, quattro macedoni, un americano – abbiamo condiviso quello spazio freddo, sporco, nel quale non c’era un letto ma solo alcune coperte. Una capanna di legno coraggiosamente costruita in una posizione assurda con una delle più microscopiche camerate dove si possa dormire. Così, abbiamo riportato a casa non solo la vetta del Cervino, ma anche l’esperienza indimenticabile di una notte in un luogo estremo.

Viaggiare – e l’alpinismo, a qualsiasi livello, è sempre un’estensione del viaggio – implica anche il dormire fuori casa, l’adagiarsi in letti diversi dalla nostra consueta cuccia. La scelta degli alberghi è spesso così oculata da divenire un esercizio maniacale, e ognuno ha la sua borsa, i suoi criteri, o anche la sua sorte – perché capita che gli imprevisti impongano soste in luoghi inaspettati, come è accaduto a noi sul Cervino.

E per quanto la Solvay Hut non sia il bivacco più alto delle Alpi – la Capanna Margherita, del CAI, è a oltre 4.500 metri e ci dormii sulla via della vetta del Monte Rosa – essa offre la possibilità di trascorrere una notte tanto scomoda ma in bilico tra le nuvole, senza un passo orizzontale possibile, quasi toccando le stelle, sentendosi parte stessa di quella ardita roccia.

A volte sì. La ricerca di letti, o giacigli, o amache, insolite, è una delle ultime frontiere di un modo di viaggiare che si ribella al prevedibile. Diversi libri (come Hotel insoliti di Steve Dobson, edizioni Jonglez) o alcuni siti ci sanno consigliare, lanciando una nuova moda e offrendo le soluzioni più stravaganti. Qualche esempio: Austria: hotel con camere in un tubo di cemento; Francia: camere in roulotte vintage; ancora Francia: una sola camera in un perfetto cubo rosso in mezzo a un campo isolato; Giappone: hotel con camere in piccole capsule; Olanda (una delle proposte più singolari): camere in scialuppe di salvataggio di una piattaforma petrolifera; Canada, paesi nordici: hotel stagionali in igloo di ghiaccio, in alcuni casi, come in Svizzera, da costruirsi da parte dei clienit; Stati Uniti: hotel in boe sottomarine, o in un ex elicottero della guardia marina; Messico: un’arena per le corride trasformata in albergo; Panama: dormire in un osservatorio astronomico; Svezia: una sola camera in una minuscola baracca galleggiante su un lago; Italia: un albergo scavato nella roccia. E molto altro, con proposte che solo vent’anni fa sarebbero state considerate follie impensabili.

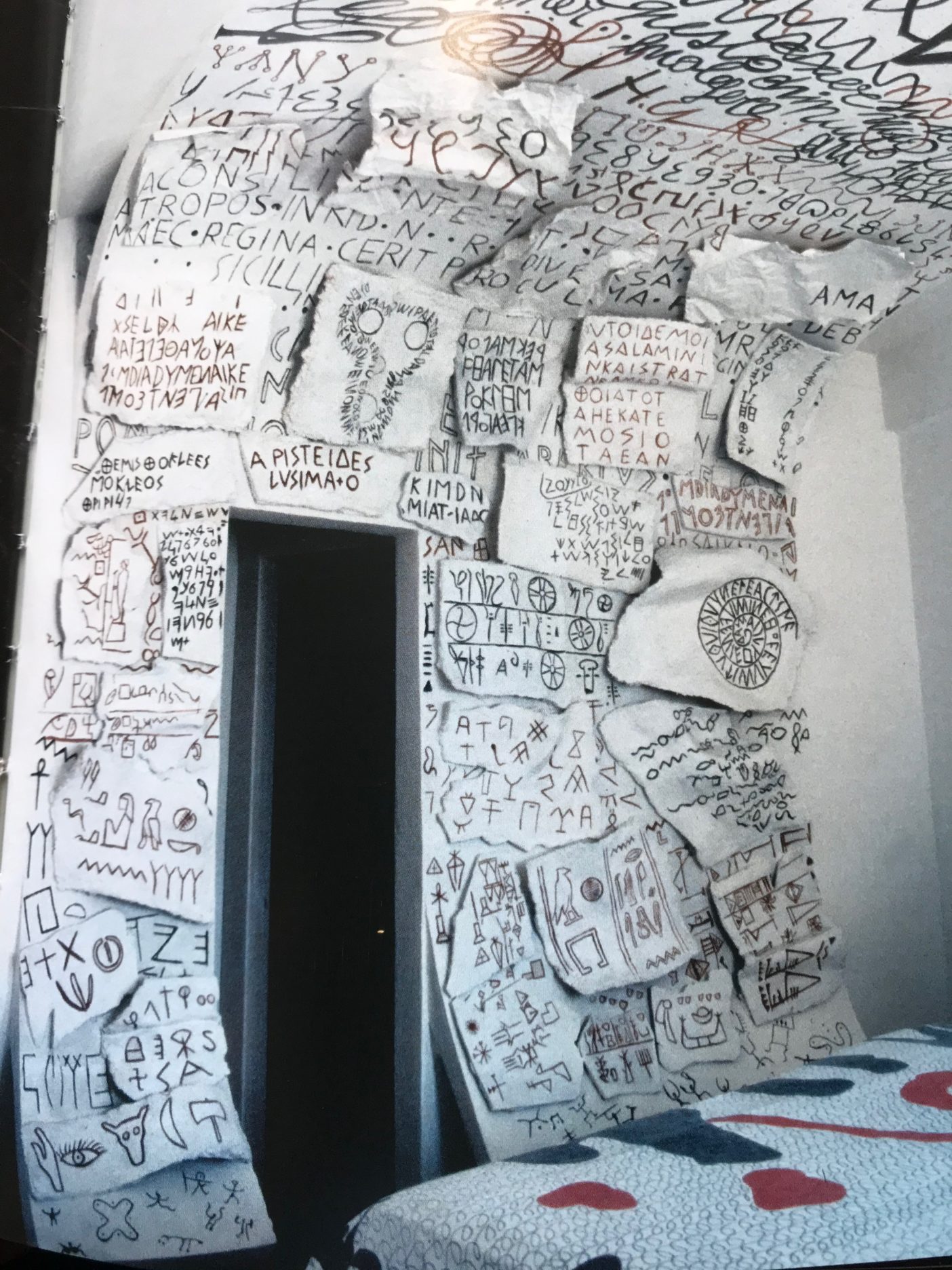

Ci sono molti alberghi di una sola camera in fari, palafitte, o strutture itineranti in camion, o ex tram e vagoni ferroviari, più ovvie chiatte e imbarcazioni di vario tipo, capanne installate in cima a un albero. E ancora, in Nuova Zelanda, un piccolo albergo di un paio di camere è stato costruito a forma di scarpone, in Italia il laboratorio di un artista sul mare o una iurta mongola in piena campagna toscana o altrove. Vi sono poi alberghi in strutture più convenzionali ma dalle forme ardite, come un’avveniristica stazione di sport invernali in Iran (proprio così). Ce n’è per tutte le latitudini, per tutti gli ecosistemi, tutte le estetiche, e nelle liste online si ritrova anche la capanna Solvay.

È una nuova frontiera del viaggiare che va oltre le diversificazioni del marketing, perché in queste camere da letto inseguiamo un’idea di noi stessi. Del resto la nostra stanza è spesso una sorta di seconda pelle, a volte prende addirittura il colore del corpo e dell’anima di chi la occupa e in un viaggio la camera d’albergo (o le sue reincarnazioni) può costituire il sigillo di quello che cerchiamo. Infatti decidiamo, o ci capita di, dormire in luoghi insoliti solo la motivazione del viaggio e il nostro stato d’animo sono particolari (proprio come accade in un’ascensione alpinistica), e non viceversa. Se dormiremo in cima a una gru – come si può fare in Olanda, una delle possibilità più gloriose – è perché la nostra vita, anche solo il nostro bisogno di diversità, è arrivato a questo punto. E allora la parte migliore e più memorabile di una giornata sarà la notte, il vissuto più intenso il dormire.

ENGLISH VERSION

In 2019 I happened to sleep in an unusual place: a high-altitude hut on the almost vertical face of the Matterhorn, just over 4,000 meters high. The “Solvay Hut” has a space of about ten square meters and, as it is wedged on the ridge, has a door on one face of the Matterhorn and a bath drain on the other. Packed up, ten climbers can sleep there, and only in an emergency. The guide and I had lingered on the way back, also to help two teams in difficulty in the descent of the final section of the pyramid below the summit. We then left them behind us and we stopped at around 7 pm at this hut – the others would arrive when we were in the dark, some even at midnight. Thus, in about ten – three Italians, two Spaniards, two Romanians, four Macedonians, one American – we shared that cold, dirty space, in which there was no bed but only a few blankets, that wooden hut, bravely built in an absurd position with one of the most microscopic “dormitories” where one can sleep. Thus, we brought home not only the summit of the Matterhorn, but also the unforgettable experience of a night in an extreme place.

Traveling – and mountaineering, at any level, is always an extension of traveling – also involves sleeping outside our home. The choice of hotels is often so carefully done, that it becomes a maniacal exercise, and each traveler has his/her own criteria or even his/her own fate – because it happens that unforeseen events require stops in unexpected places, as happened to us on the Matterhorn.

And although the Solvay Hut is not the highest hut in the Alps – the Capanna Margherita, of the Italian Alpine Club, is over 4,500 meters and I slept there on the way to the summit of Monte Rosa – it offers the possibility of spending a night so uncomfortable but in hovering among the clouds, almost touching the stars, feeling part of that daring rock.

Sometimes yes. The search for unusual beds, beds or hammocks is one of the last frontiers of a way of traveling that rebels against the predictable. Books (such as Unusual Hotels by Steve Dobson, Jonglez editions) or sites advise us by launching a new fashion and offering the most extravagant solutions. A few examples: Austria: hotel with rooms in a concrete tube; France: rooms in vintage caravans; again France: a single room in a perfect red cube in the middle of an isolated field; Japan: hotel with rooms in small capsules; Holland (one of the most unique proposals): rooms in lifeboats of an off-shore oil platform; Canada, Nordic countries: seasonal hotels in ice igloos, in some cases, as in Switzerland, to be built by clients. United States: hotel in underwater buoys, or in a former marine guard helicopter; Mexico: a bullfighting arena converted into a hotel; Panama: sleeping in an astronomical observatory; Sweden: a single room in a tiny floating shack on a lake; Italy: a hotel carved into the rock. And much more, with proposals that only twenty years ago would have been considered unthinkable follies. There are many one-bedroom hotels in lighthouses, stilt houses, or traveling truck structures, or former trams and railroad cars, most obvious barges and boats of various kinds, tree-top huts. And again, in New Zealand, a small hotel with a couple of rooms was built in the shape of a boot, in Italy an artist’s workshop by the sea or a Mongolian yurt in the Tuscan countryside or elsewhere. Then there are hotels in more conventional structures but with bold shapes, like a futuristic winter sports resort in Iran (that’s right). There is something for all latitudes, for all ecosystems, all aesthetics, and the Solvay hut is also found in the online lists.

It is a new frontier of travel that goes beyond the diversifications of marketing because in these bedrooms we pursue an idea of ourselves. After all, our room is often a sort of second skin, sometimes it even takes the color of the body and soul of the occupant and on a trip, the hotel room or its reincarnations can be the seal of that that we seek. In fact, we decide or happen to sleep in unusual places only if the motivation for the trip and our state of mind are particular (just as happens in a mountaineering climb), and not vice versa. If we sleep on top of a crane – as can be done in Holland, one of the most glorious possibilities – it is because our life, even just our need for diversity, has come to this point. And then the best and most memorable part of a day will be the night, the most intense experience will be sleeping.