Mario Fantin pioniere del cinema di alta quota

Fino a fine febbario 2025 al Lagazuoi è visitabile una duplice mostra settanta anni dopo la conquista del K2. Mario Fantin e il libro "K2 sogno vissuto".

Fino a fine febbario 2025 al Lagazuoi è visitabile una duplice mostra settanta anni dopo la conquista del K2. Mario Fantin e il libro "K2 sogno vissuto".

English translation below

Ai quasi 2.750 metri della stazione di arrivo della dolomitica funivia del Lagazuoi si trova forse il più alto centro espositivo d’Europa. L’anno scorso fu presentato uno splendido progetto sulla memoria dei ghiacciai alpini , mentre quest’anno, fino a fine febbraio, è allestita una duplice mostra sulla conquista del K2.

Si comincia con una spedizione di oggi che, nel racconto di Massimiliano Ossini, ripercorre le orme di quella del Club Alpino Italiano del 1954 e che, con i suoi filmati e le interviste ai suoi artefici, rende l’idea di quanto tempo sia passato anche lassù in settant’anni. Skardu, la capitale del Baltistan, che quando ci passai nel 1990 era poco più che un villaggio, va ormai per i centomila abitanti, gli sherpa camminano finalmente con scarpe da montagna, l’attrezzatura medica al seguito pare imponente. Poi nelle interviste si suona la solita musica: l’entusiasmo di trovarsi al cospetto del K2, la più difficile vetta montagna del mondo, la vertigine himalayana dei partecipanti, il solito inno alla pastasciutta cucinata in quota per la delizia di sherpa e alpinisti: l’Italia che va a giro per il mondo non cambia, e non cambiano quelle emozioni che ci fanno sentire piccoli piccoli dinanzi a una piramide che solo a vederla mette davvero tutti in riga – molto più che l’Everest.

L’altra metà del progetto è su un aspetto specifico della gloriosa e controversa conquista del K2 nel 1954, e in questo sta il valore della mostra, piccola ma ricca di filmati dell’epoca, testimonianze vecchie e di oggi, e testi: il protagonista per una volta non sono gli alpinisti, la coppia Compagnoni e Lacedelli che piantarono il tricolore sulla vetta, o Bonatti che con lo sherpa quasi perse la vita per portare le bombole di ossigeno fino alla fine dovette trascorrere una notte all’addiaccio essendogli negata la possibilità di andare oltre e dare anche lui l’assalto finale. Il primattore non è nemmeno quel complesso personaggio che fu Arturo Desio, il re assoluto dell’impresa, che si prese la responsabilità di escludere Bonatti senza mai riconoscere alcuna responsabilità in una scelta controversa che poteva diventare tragedia ed errore fatale, ma che congegnò la spedizione con una disciplina militare e un’organizzazione scientifica e mastodontica che non poteva fallire – e non fallì.

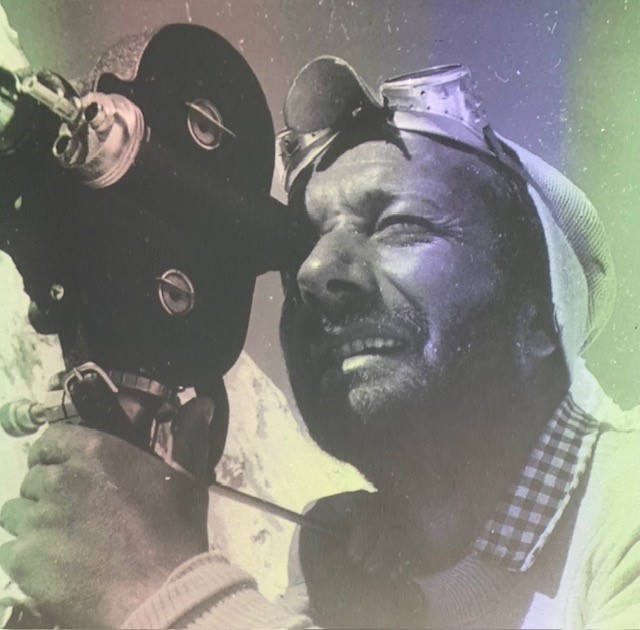

L’eroe della mostra del Lagazuoi è Mario Fantin (1921-1980), il cronista ufficiale del K2, non solo autore del libro K2 Sogno vissuto, un classico ancora letto che dell’avventura italiana fu l’interpretazione autentica, ma anche fotografo e ancor più cineasta della scalata.

Desio in questo vide giusto: come Hillary con il grande James Morris – poi divenuta Jan Morris, e una delle più grandi scrittrici di viaggio del ‘900 – per Everest, Desio affidò a Fantin un ruolo che fu cruciale: documentazione, preparazione della memoria da trasmettere, e innovazione. Perché a differenza delle altre imprese alpinistiche dell’epoca, Fantin curò la riprese di filmati in alta quota, che poi confluirono nel film Italia K2 che ha fatto epoca per tecnica di ripresa. Ancorché, altra ingiustizia di quella spedizione, non accreditato come regista di quell’opera d’arte, ma solo come responsabile della fotografia, Fantin si impose nel mondo come un precursore del cinema di alta quota.

Schivo – “Mi sono estraniato, mi sono escluso; mi sono messo da parte per osservare e filmare. Obbedivo alla consegna datami dal capo spedizione Arturo Desio: “Per fare il film non dovrà mai fermare un solo uomo in marcia, non dovrà mai in alcun modo , turbare o modificare il normale svolgimento della spedizione”

sconosciuto al grande pubblico, dopo il K2 divenne un riferimento dell’etno-cinematografia, documentando decine di spedizioni dall’Africa alla Groenlandia e diffondendo “alle masse” il sapore e la bellezza di mondi allora ancora sconosciuti. Al Museo Nazionale della Montagna riuscì ad assemblare quella che tuttora è la più vasta cineteca del mondo di spedizioni alpinistiche extra-europee.

Per arrivare a tanto, bisogna combinare eccellenze diverse: pratica dell’alpinismo, senso estetico e occhio registico, sensibilità per i paesaggi naturali e umani esotici, conoscenze tecniche e propensione ad avventurarsi in campi inesplorati nell’arte cinematografica.

Tanto ci volle per fare di Fantin un taumaturgo dell’alpinismo –

“Qui ogni metro di film richiede fatica fisica e mentale” –

che con i suoi obiettivi e la sua penna ha trasmesso a chi restava a valle, in pagine e immagini tra nirvana e brivido, le sfide dei rocciatori come eroi di nuove fiabe.

ENGLISH VERSION

An exhibition at Lagazuoi seventy years after the conquest of K2

At almost 2,750 meters above sea level, the arrival station of the Dolomite cable car of Lagazuoi, is perhaps the highest exhibition center in Europe. Last year presented a splendid project on the “memory of Alpine glaciers” and until February has a show on K2.

We begin with a recent expedition that, in Massimiliano Ossini’s story, retraces the footsteps of the Italian Alpine Club’s expedition in 1954 and which, with its films and interviews with its creators, offers an idea of how much time has passed up there in seventy years. Skardu, the capital of Baltistan, which when I visited it in 1990 was little more than a village, now has a population of almost one hundred thousand, the Sherpas finally walk with proper mountain shoes, the medical equipment in tow seems impressive. Then, in interviews, the usual music plays: the enthusiasm of finding oneself in the presence of K2, the most difficult mountain peak in the world, the Himalayan vertigo of the participants, the usual hymn to pasta cooked at high altitude for the delight of sherpas and mountaineers: the Italy that goes around the world does not change, and those emotions that make us feel very small in front of a pyramid that just by looking at it really puts everyone in line – much more than Everest. The other half of the project is on a specific aspect of the glorious and controversial conquest of K2 in 1954, and this is the value of the exhibition, small but rich in original films, old and current testimonies, and texts: the protagonists for once are not the mountaineers, the Compagnoni and Lacedelli couple who planted the Italian flag on the summit, or Bonatti who with one Sherpa almost lost his life carrying the oxygen tanks and had to spend a night out in the cold, being denied the possibility of going further and giving the final assault himself. The leading actor is not even that complex character that was Arturo Desio, the master of the enterprise, who took the responsibility of excluding Bonatti without ever acknowledging any responsibility in a controversial choice that could have turned into a tragedy and a fatal error, but who lead the expedition with a military discipline and a scientific and mammoth organization that could not fail – and did not fail.

The hero of the Lagazuoi exhibition is Mario Fantin (1921-1980), the official chronicler of the Italian K2, not only author of the book K2 Sogno vissuto, a classic still read that was the authentic interpretation of the adventure, but also photographer and even more filmmaker of the climb. Desio was right in this: like the great James Morris – later Jan Morris, and one of the greatest travel writers of the 20th century, for Hillary’s Everest, he entrusted Fantin with a role that was crucial: documentation, preparation of the memory to be transmitted, and innovation. Because unlike other mountaineering enterprises of the time, Fantin took care of filming high altitude footage, which later flowed into the film Italia K2 which made history for its filming technique. Although, another injustice of that expedition, not credited as director of that work of art, but only as head of photography, Fantin imposed himself in the world as a precursor of high altitude cinema.

Shy – “I alienated myself, I excluded myself; I put myself aside to observe and film. I obeyed the instructions given to me by the expedition leader Arturo Desio: “To make the film you must never stop a single man on the march, you must never in any way disturb or modify the normal course of the expedition” – unknown to the general public, after K2 he became a point of reference for ethno-cinematography, documenting dozens of expeditions from Africa to Greenland and spreading “to the masses” the flavor and beauty of worlds that were still unknown at the time. At the National Mountain Museum he managed to assemble what is still the largest film library in the world of non-European mountaineering expeditions.

To achieve this, he had to combine different skills: mountaineering practice, aesthetic sense and directorial eye, sensitivity for exotic natural and human landscapes, technical knowledge, and a propensity to venture into unexplored fields in the art of cinema.

It took that much to make Fantin a miracle worker of mountaineering – “Here every meter of film requires physical and mental effort” – who with his lenses and his pen transmitted to those who remained down in the valley, in pages and images between nirvana and thrill, the challenges of climbers as fairy tales heroes.