Piccoli pellegrinaggi urbani a Venezia: viaggi contro la pandemia

Una immagine votiva e una singolare pietra rossa nella Venezia che tra le sue tante suggestioni di viaggio ha anche i suoi pellegrinaggi per i tempi di pandemia.

Una immagine votiva e una singolare pietra rossa nella Venezia che tra le sue tante suggestioni di viaggio ha anche i suoi pellegrinaggi per i tempi di pandemia.

(English translation below)

In questo 2020 così incompatibile con i viaggi, dopo molte controverse discussioni, le istituzioni veneziane hanno salvato in extremis la festa che da oltre tre secoli si celebra attraversando il Canal Grande il 21 novembre. Grazie a un curioso ponte votivo allestito per l’occasione, si potrà raggiungere l’immensa chiesa circolare della Salute, edificata dal Longhena per la sospirata sconfitta della peste del 1630; una piaga che sterminò 80.000 veneziani. Sarebbe stato quasi beffardo non poter invocare la miracolosa madonna proprio durante l’attuale epidemia, anzi pandemia, che di per sé è anche peggio.

Per quanto breve, questo rito è una delle forme più profonde del viaggio: il pellegrinaggio (al quale è imparentata la processione). Ormai non vi si fa più ricorso, e mentre invochiamo vaccini, adeguate terapie intensive, finanziamenti europei, chiarezza dell’informazione, disciplina sociale, e buona sorte per tutti noi, l’attuale pandemia ha escluso dal sentire collettivo il bisogno o la speranza della divina salvezza dispensata da questa categoria del viaggio – almeno per i cattolici, molto meno per i protestanti. Eppure per secoli e ancora recentemente, per sconfiggere le epidemie ci si affidava soprattutto alla fede, e più esattamente a dei punti cruciali catalizzatori di tensioni e dispensatori di protezioni – santuari, statue miracolose, reliquie. Questione di religione, o di superstizione, comunque la regola è sempre che la richiesta di protezione implica uno spostamento, un brevissimo o faticoso viaggio, perché la salvezza ce la dobbiamo andare a cercare con un cammino che è di per sé un atto volitivo di fede.

Venezia, rivelatrice per la sua stessa natura dei meccanismi interni del viaggio (lo sono il suo essere Asia, la trasgressione del carnevale, Corto Maltese, il porto, luoghi apicali della cultura del viaggio come le Corderie dell’Arsenale, l’aeroporto alla De Chirico del Lido, i labirinti dell’estuario da percorrere in canoa, e molto altro) ha una costellazione di luoghi che combina pellegrinaggio e infezioni: l’ex sanatorio dell’isola La Grazia, che era ricovero dei pellegrini della Terra Santa, quello più recente di Sacca Sessola, il Lazzaretto Nuovo, il Lazzaretto Vecchio, una vasta schiera di icone orientale protettrici conservate nelle varie chiese cittadine.

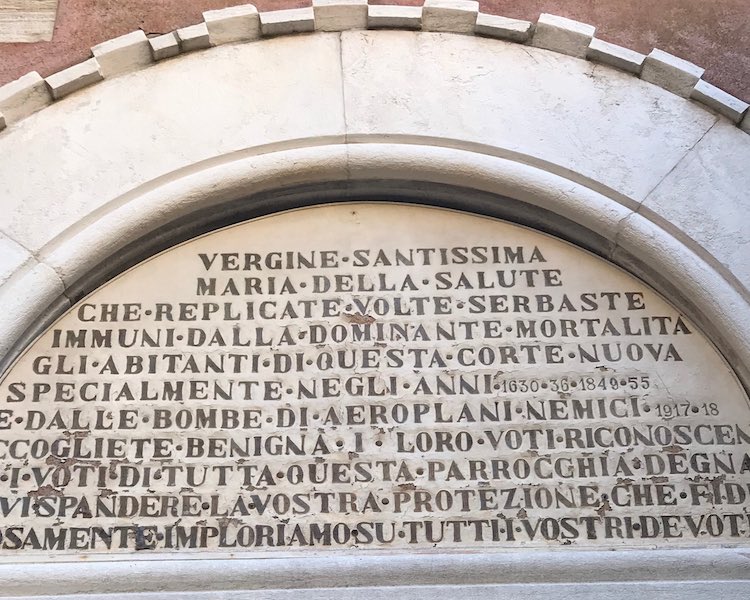

Con le esitazioni dovute alla mia fede di protestante e alla mia cultura, anche politica, laica, domenica scorsa ho compiuto anche io il mio pellegrinaggio veneziano, recandomi non alla Salute ma al sotoportego della Corte Nova nel sestriere di Castello. Vi si trova una venerata immagine della vergine che ha protetto gli abitanti della zona dalla peste del 1630 e poi da altre epidemie, e più recentemente dalla prima guerra mondiale. Intorno alle pareti, una serie di dipinti rappresentano i devoti e tra questi anche ammalati di malattie infettive, un tempo pochi ci avrebbero fatto caso, oggi fanno una certa impressione.

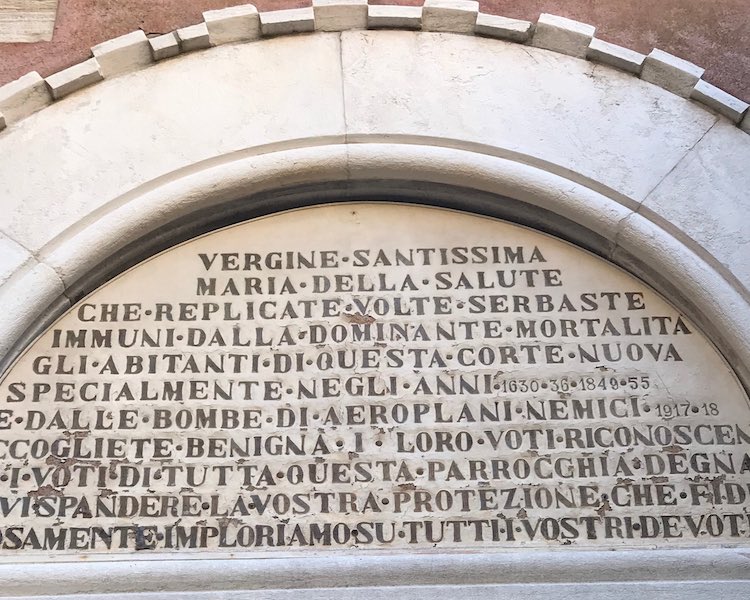

Per terra, sul selciato c’è una pietra rettangolare rossa, la sola colorata. È la meta del piccolo pellegrinaggio, il segno della posizione giusta per invocare la protezione dalle epidemie. Anche se lo abbiamo dimenticato, anche se non lo abbiamo mai saputo, è probabile che nelle vicinanze di dove viviamo vi siano piccoli altari a cui rivolgersi in tempi ordinati e in tempi di calamità.

Sul singolare rettangolo della Corte Nova non c’era nessuno, il distanziamento era rispettato. Idealmente, tutto il mondo si potrebbe dare appuntamento su quella pietra rossa, appartato spazio di una forma di salvezza alla quale crediamo sempre meno ma che ci sollecita a guardare oltre le infrante certezze e a intraprendere un cammino.

E il cammino, anche pochi passi a Venezia, è sempre una medicina.

Year 2020 – the no-travelling year. Yet, after many controversial discussions, the Venetian institutions eventually agreed to confirm the popular celebration that since more than three centuries the city has been celebrating by crossing the Grand Canal on 21st November. Through a curious votive bridge set up for the occasion, you will be able to reach the immense circular church of the Salute, built by Longhena for the long-awaited defeat of the plague of 1630, which had exterminated 80,000 Venetians. It would have been a paradox not being able to invoke the miraculous Madonna during the current epidemic – indeed a pandemic, which is even worse. Although not demanding much tine, this rite is one of the deepest forms of the journey: the pilgrimage (to which the procession is related).

While we call for vaccines, adequate intensive care, European funding, clarity of information, social discipline, and good luck for all of us, the current pandemic has excluded the need or hope of divine salvation dispensed from pilgrimage – a special category of travel, at least for Catholics – much less for Protestants. Yet for centuries and again recently, in order to defeat epidemics, people relied mostly on faith, and more precisely on crucial places catalysts of tensions and dispensers of protection – sanctuaries, miraculous statues, relics. A matter of religion, or of superstition, the rule is always that the request for protection implies a “psychical transfer”, a very short or a long journey, because we must seek salvation through a path that is in itself a wilful act faithful. Venice is a city able to revel by its very nature the internal mechanisms of travelling: its being Asia, the transgression of the carnival, Corto Maltese, its port, top places of the culture of travel such as the Arsenale Corderie, the De Chirico-like airport in Lido, the labyrinths of the estuary to be explored by kayak, and much more. And as a consequence, Venice has a constellation of places that combines pilgrimage and infections: the former sanatorium of the island La Grazia, which was a shelter for pilgrims from the Holy Land, the most recent of Sacca Sessola, the Lazzaretto Nuovo, the Lazzaretto Vecchio, a vast array of protective oriental icons preserved in the various city churches. Although with the hesitation due to my Protestant faith and my secular culture, even politically, last Sunday I also made my Venetian pilgrimage, going not to Salute but to the sotoportego of Corte Nova in the Castello district. There, a venerated image of the virgin protected the inhabitants of the area from the plague of 1630 and then from other epidemics and more recently from the First World War. Around the walls, a series of paintings depict devotees and characters affected by infectious diseases – images that once few would have noticed, but that today make a certain impression. On the ground, on the pavement there is a red rectangular stone, the only coloured one. This is the final destination of the small pilgrimage, the sign of the right position from where one can invoke protection from epidemics.

Probably we have forgotten, or even ne never knew this kind of small corners of protections; however, it is likely that in the vicinity of where we live there are small altars to turn to in times of calamity. There was no one on the singular rectangle of the Corte Nova and the required social distancing was respected. Ideally, the whole world could meet on that red stone, the secluded space of a form of salvation in which we believe less and less but which urges us to look beyond today broken certainties and to undertake a journey. And the journey, even a few steps in Venice, is always a kind of medicine.