Il viaggio finale dei ghiacciai, in un sito e un’app

La Memoria dei Ghiacci, un requiem e un monito a fare in fretta. Il progetto del Ministero della Ricerca sui ghiacciai, un sito e una app

La Memoria dei Ghiacci, un requiem e un monito a fare in fretta. Il progetto del Ministero della Ricerca sui ghiacciai, un sito e una app

(English translation below)

Tra i grandi viaggiatori vi sono i ghiacciai, con i loro passi impercettibili. Il loro viaggio è grandioso per dimensioni e mai solitario: con loro si muovono i cambi climatici, i livelli delle acque del mare, le temperature, la nostra vita. Il loro è un lungo viaggio per rattrappimento, con le acque che proseguono lontano, e il ghiaccio che si ritira, svelando rocce mai viste dalle nostre generazioni, mutando i paesaggi, lasciando le tracce del loro cammino – millenario ma pur sempre passaggio.

L’alpinista assiste sgomento e meravigliato a questo colossale scompaginamento del paesaggio: da ragazzino imparai la tecnica di scalata sul ghiaccio con un’ascensione alla Grober (3.500 metri) sul Monte Rosa, un gomito che da tutto bianco è oggi un roccia stondata. Il ghiaccio se ne è andato da lì come da buona parte di quella che un tempo era l’immensa morena che scendeva verso Macugnaga. Dall’altra parte dell’arco alpino, il Tricorno sloveno, vetta delle Alpi orientali di poco sotto i 3.000 metri, è oggi una bella salita tutta su roccia, e si stenta a credere alle fotografie di un secolo fa che lo ricordano in un paesaggio tutto ghiacciato.

Di quelle epoche, che erano soltanto ieri, sconquassate da cambiamenti colossali, rimangono appunto i ricordi – personali di alpinista, della vita delle comunità, e ancora di più della geologia, della conformazione delle montagne, del loro aspetto esteriore e di ciò che stava sotto la maestosa crosta bianca. La memoria dei ghiacci è uno splendido e doveroso progetto sostenuto dal Ministero della Ricerca e condotto dall’Istituto di Scienze Polari del CNR, dalla Ice Memory Foundation, da Ca’ Foscari, dal Comitato Glaciologico Italiano e da altre istituzioni che hanno congiuntamente realizzato un sito, un’app per condividere il lavoro dei ricercatori, un lavoro sia di monitoraggio scientifico costante che di divulgazione, con tanto di mostre itineranti.

Per chi sia alpinista, il sito e l’app sono l’impressionante segnalibro di ricordi personali, di confronti con ciò che era stata una salita alla Capanna Margherita, alla vetta della Marmolada o del Monte Bianco, e anche l’album del loro aspetto oggi e della previsione di sopravvivenza.

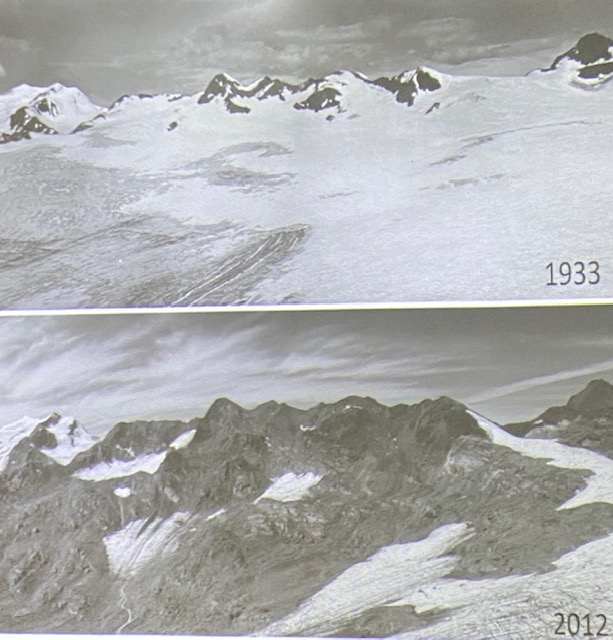

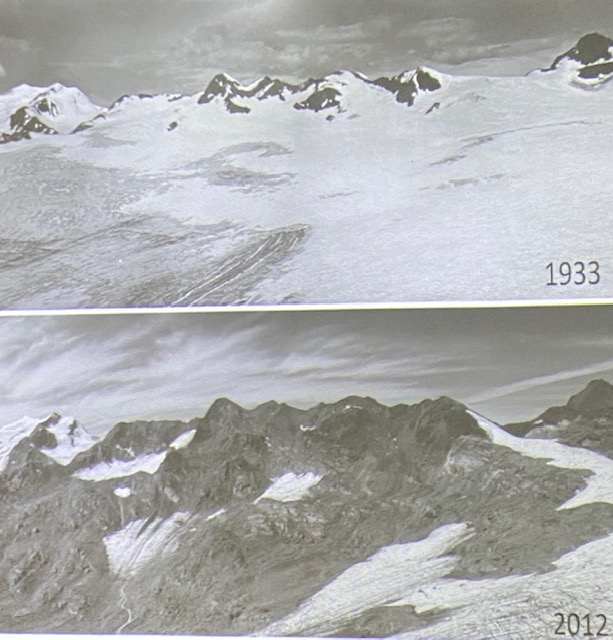

Repertoriando oltre un centinaio di ghiacciai, il sito – in continuo aggiornamento – permette altrettanti viaggi virtuali che mettono a confronto fotografie di ieri e di oggi, mettendoci di fronte a cosa del ghiaccio rimarrà a fine secolo. E il bianco, quel magnifico solido e liquido glaciale bianco, è destinato sempre più a trasformarsi nel colore grigio e bruno e ocra della roccia.

Questi viaggi sono spesso dolorosi, sigillati per alcuni ghiacciai dalla loro sentenza di morte, anche in caso di azioni immediate e di significative riduzioni delle emissioni: è l’ormai è troppo tardi che segna la fine nei prossimi decenni delle distese ghiacce dell’Adamello, del Gran Zebrù sull’Ortles, e di molti altri. Per loro, il dato di quanto rimarrà a fine secolo è il perentorio “0,0%”. I loro sono viaggi d’addio, requiem di rimpianti per ciò che si sarebbe dovuto fare o quantomeno provare a fare. In una mostra di quasi vent’anni fa, al Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino

“I tempi stanno cambiando – come varia il clima: conoscenze attuali e scenari futuri”,

si ricordava di Svante Arrhenius, chimico e fisico svedese, che nel 1896 teorizzò che l’utilizzo dei combustibili fossili avrebbe aumentato la concentrazione atmosferica di biossido di carbonio e quindi alterare il bilancio energetico del pianeta e aumentato la temperatura terrestre. Fu deriso dalla comunità scientifica, e ci volle un secolo per accettare la sua intuizione solitaria.

Alcune vecchie conoscenze dei montanari stanno opponendo resistenze logoranti: del ghiacciaio, che pure è tutto esposto a nord, della Marmolada si potrà ancora salvare il 14% ma solo se si agirà in fretta, mentre per il Lys, il più grande del Monte Rosa, tutto dipende dai tempi e dalla qualità delle azioni di contrasto ai cambiamenti climatici: ne potrà rimanere il 91% o solo il 9%. Salviamo il salvabile, non sarà mai troppo tardi.

Per alcuni, invece c’è solo da accudirli amorevolmente nel loro ultimo stadio di vita, nell’agonia della loro strenua resistenza: il mio beniamino è il più meridionale d’Europa, quel Calderone del Gran Sasso dove volli portare i figli perché anche se ormai esile, un ghiacciaio sull’Appenino non lo vedranno mai più. Un ghiacciaio che ancora merita questo nome, ma ormai minimo: meno 0,1 chilometri quadrati, studiati e accuditi con rivelazioni in profondità (fino a 27 metri), rifocillato d’inverno e ancora appeso a un esile filo di persistenza in ogni stagione grazie a delle condizioni di isolamento termico eccezionale. Per noi alpinisti dell’Italia centrale, è quasi il ghiacciaio di casa, ai cui piedi dopo la pandemia si propose di arrivare in Vespa.

Addio Calderone, addio Grober, Ventina, e tanti altri. La memoria dei ghiacci è un bel libro di ricordi da sfogliare, ma è soprattutto il monito urgente a invertire la rotta. Il Titanic andava dritto verso l’iceberg, e fece 1513 vittime. Quanto tempo occorreva per la virata? Cosa possiamo imparare da quella tragedia?

ENGLISH VERSION

The Memory of the Ice project, a requiem and a warning to hurry

Among the great travelers are the glaciers, with their imperceptible footsteps. Their journey is grandiose in size and never solitary: climate changes, sea water levels, temperatures, our lives move with them. Theirs is a long journey of shrinkage, with the waters that continue into the distance, and the ice that retreats, revealing rocks never seen by our generations, changing the landscapes, leaving traces of their path – thousands of years old but still a passage.

The mountaineer watches in dismay and amazement at this colossal disruption of the landscape: as a boy I learned the ice climbing technique with an ascent of the Grober (3,500 metres) on Monte Rosa, an elbow which from completely white is now a rounded stoned rock. The ice has disappeared from there as well as from most of what was once the immense moraine that descended towards Macugnaga. On the other side of the Alpine arch, the Slovenian Triglav, peak of the Eastern Alps just under 3,000 metres, is today a beautiful climbing entirely on rock, and it is hard to believe the photographs from a century ago which recall it in a landscape all frozen. Of those eras, which were only yesterday, shaken by colossal changes, what remain are the “memories” – personal as a mountaineer, of community life, and even more so of geology, of the conformation of the mountains, of their external appearance and of what it was under the majestic white crust. The memory of the ice is a splendid and dutiful project supported by the Ministry of Research and conducted by the Institute of Polar Sciences of the CNR, by the Ice Memory Foundation, by Ca’ Foscari University, by the Italian Glaciological Committee and by other institutions that have jointly created a site, an app to share the work of researchers, a job of both constant scientific monitoring and dissemination, complete with traveling exhibitions.

For those who are mountaineers, the site and the app are the impressive bookmark of personal memories, of comparisons with what a climb to Capanna Margherita, to the summit of Marmolada or Mont Blanc had been, and also the album of their appearance today and the survival forecast.

Listing over a hundred glaciers, the site – continuously updated – allows as many virtual journeys that compare photographs of yesterday and today, putting us in front of what will remain of the ice at the end of the century. And the white, that magnificent white glacial solid and liquid, is increasingly destined to transform into the gray, brown and ocher color of the rock.

These journeys are often painful, sealed for some glaciers by their death sentence, even in the case of “immediate actions” and significant “emission reductions”: it is already now too late ice to stop the dying of the glaciers of the Adamello, of the Gran Zebrù on the Ortles, and of many others. The forecast, for all of them, of what is going to remain is “0,0%”. These are farewell journeys, requiems of regret for what should have been done or at least tried to do.

In an exhibition from almost twenty years ago, at the Regional Museum of Natural Sciences of Turin, – “Times are changing – how the climate changes: current knowledge and future scenarios”, was remembered by Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish chemist and physicist, who in 1896 theorized that the use of fossil fuels would increase the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and therefore alter the energy balance of the planet and increased the Earth’s temperature. He was derided by the scientific community, and it took a century to accept his solitary intuition.

Some old acquaintances of the mountaineers are putting up exhausting resistance: of the glacier, which is all exposed to the north, of the Marmolada, 14% can still be saved but only if we act quickly, while for the Lys, the largest of Monte Rosa, everything depends on the timing and quality of the actions to combat climate change: 91% or only 9% may remain. Let’s save what can be saved, it will never be too late.

For some, however, there is only a need to look after them in their last stage of life, in the agony of their strenuous resistance: my favorite is the southernmost in Europe, that Calderone of Gran Sasso, where I wanted to bring my children because even if now thin, they will never see again a glacier on the Apennines. A glacier that still deserves this name, but now minimal: less than 0.1 square kilometres, studied and looked after with depth revelations (up to 27 metres), refreshed in winter and still hanging on by a thin thread of persistence in every season thanks to its exceptional thermal insulation. For us mountaineers from central Italy, it is almost our home glacier, at the foot of which after the pandemic we proposed to arrive by Vespa.

Goodbye Calderone, goodbye Grober, Ventina, and many others. “The memory of the ice” is a beautiful book of memories to leaf through, but above all it is the urgent warning to reverse course. The Titanic headed straight for the iceberg, causing 1,513 victims. How long would have take the turn? What can we learn from that tragedy?