Una storia personale e 2 libri per capire se ‘talebano’ è un insulto

La parola 'talebano' e un caso che ha fatto giurisprudenza: significati, sfumature e ambiguità di un termine che è entrato nel nostro vocabolario.

La parola 'talebano' e un caso che ha fatto giurisprudenza: significati, sfumature e ambiguità di un termine che è entrato nel nostro vocabolario.

(English translation below)

Grandi viaggiatrici le parole. Ve ne sono che ci visitano da lontano, alcune restano con noi e cominciano ad abitare i nostri dizionari, benvenute perché siamo noi che le accogliamo nel nostro linguaggio corrente, o malviste, a volte anche a ragione, da alcuni difensori della purezza.

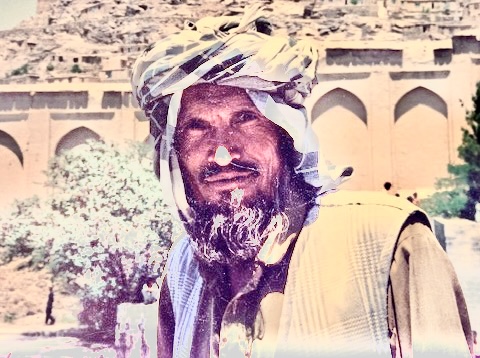

Vi sono casi estremi nei quali questi viaggi creano scompiglio, perfino processi penali. Si veda il significato della parola talebano sulla Treccani, sulla quale sono stato interpellato dal Tribunale Militare di Verona in una storia che ha qualcosa dei film della nostra commedia popolare. Una storia dove viaggiano insieme Afghanistan e Italia, serio e faceto, semantica e giustizia.

Tutto cominciò con la telefonata di un cappellano militare che aveva letto qualche mio libro sull’Afghanistan e mi raccontò di un militare che durante una litigata dette del talebano a un collega, beccandosi una denuncia per diffamazione.

Ma talebano è un insulto? Così mi presentò la richiesta, in seguito formalizzata da un avvocato, di spiegare come perito, come persona esperta di Afghanistan e dei suoi usi, il significato di talebano. Non basta il vocabolario, come in altro contesto scrisse anche Lorenzo Gasparrini su Rewriters, e forse si potrebbe cominciare da qualche buon libro, tra i quali spiccano quelli di Ahmed Rashid (intitolato proprio Talebani) o di Peter Marsden (The Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan).

Fu un po’ una seccatura – andare a Verona a una certa ora, per un’udienza che cominciò con un tale ritardo da farmi perdere l’aereo di ritorno, il tutto senza alcun rimborso – ma anche un’esplorazione sia nei meandri della giustizia militare, sia nel viaggio della parola incriminata. Agli atti era già presente la seguente breve memoria sulla parola e sul concetto di talebani:

1) La parola Talib è presente in varie lingue asiatiche, e nel caso afghano proviene dal vocabolario pashtu, dove, come anche in arabo o i persiano, significa studente. La parola taliban significa invece studenti, sia in pashtu che in persiano, mentre in arabo equivale a due studenti. Non è rivolta a un particolare gruppo etnico, anche se i talebani (in italiano diventato talebani) sono quasi esclusivamente pashtu, nel linguaggio locale.

2) Nella pratica corrente, gli studenti sono intesi come studenti delle scuole religiose, madras, o coraniche, visto che nelle tradizioni locali, le scuole erano spesso gestite dalle autorità religiose, e che in ogni caso i curricula educativi rispettavano e in buona parte tuttora rispettano i precetti religiosi.

3) La parola, non ha dunque, di per sé, alcuna connotazione negativa. Al contrario, può essere sinonimo di persona disciplinata, studiosa, metodica. In ogni caso, è termine di uso corrente in moltissimi Paesi.

4) Tuttavia, il termine talebani indica anche un gruppo di fondamentalisti islamici che ha (come in altri casi: Hamas, Hezbollah), sia una sfera civile sia una militare. Come è noto, i talebani hanno raggiunto il potere in quasi tutto l’Afghanistan dal 1996 fino alla fine del 2001. Nella loro carta del 1996, si può leggere “la nostra legge è solo in conformità con la Sharia del profeta, senza sofferenza, egoismo e oppressione” – una dichiarazione di intenti rassicurante.

Nella pratica, però, il potere civile dei talebani si è espresso in alcune delle più barbare e inumane pratiche, con una discriminazione legislativa e di fatto strutturale nei confronti delle donne, con la pratica delle lapidazioni pubbliche negli stadi, con il divieto al possesso di fotografie o di esercitare un certo numero di professioni o attività (dalla pesca agli aquiloni, molto popolari in Afghanistan). Il termine talebano in questo caso diventa negativo, come qualcuno quasi barbaro, arretrato, oscurantista.

5) Inoltre, i talebani hanno un’attività insurrezionale molto diffusa in Afghanistan. Essi sono impegnati su due fronti: nei confronti del governo e delle forze armate afghane, e nei confronti degli avamposti che Daesh – o ISIS, o Stato islamico – è riuscito ad attivare nel Paese.

Infatti la piattaforma ideologica e l’agenda politica dei talebani sono molto diverse e quasi opposte a quelle dell’ISIS (in termini sommari: i talebani, come Hamas o Hezbollah, sono elementi nazionali e di fatto etnici, e ripudiamo attività terroristica fuori dai propri confini, mentre l’ISIS ha una visione internazionalista e lotta anche per lo smantellamento degli Stati arabi o islamici esistenti). Questo conflitto aperto tra i due gruppi ha portato i talebani a ricevere aiuto militare anche dalla Russia, in funzione sia anti NATO che anti-ISIS).

6) Per quanto questa loro peculiare posizione, renda i talebani a volte perfino alleati di certe politiche europee, essi sono comunque nemici, sia del governo afgano e che della coalizione internazionale in suo appoggio a cui partecipa anche l’Italia. Il termine talebano, in questo caso, può diventare particolarmente negativo laddove coincide con un nemico.

7) Ma a rendere ancora di più complessa la posizione di talebani e indirettamente la connotazione del termine, questi nemici sono riconosciuti come interlocutori negoziali in una trattativa di pace avviate sotto l’egida degli Stati Uniti a Doha lo scorso anno. Per quanto l’esito di questo tavolo sia incerto (e personalmente prevedo che non porterà a risultati), attraverso questo negoziato ufficiale i talebani acquisiscono un ruolo istituzionale riconosciuto. La parola talebano sfuma ancora una volta in accezioni ambigue, poiché domani essi potrebbero essere parte di una coalizione governativa di un Paese pienamente riconosciuto dall’Italia.

Seguiva il mio nome e una lunga lista di referenze – le qualifiche di responsabile informazione per l’ONU in Afghanistan, deputato europeo membro della delegazione per l’Afghanistan, attuale desk-officer per l’Afghanistan al Parlamento Europeo oltre che Capo Unità per l’Asia, e un congruo numero di libri e articoli scritti sul tema.

Per la prima volta, una mia acclarata competenza avrebbe contribuito a fare della giurisprudenza. Perché in gioco c’era sia l’esito della diffamazione, ma anche il possibile sdoganamento o l’incriminazione della fatidica parola per casi futuri. Su questo si concentrò il dibattito con i giudici e gli avvocati, che non fu senza interesse, spaziando da un resoconto di un mio incontro con i talebani fino alla Curva sud dell’Olimpico di Roma.

Quest’ultimo fu forse fu l’argomento definitivo, perché uno storico gruppo ultras di tifosi giallorossi si chiama Fedayn, che in arabo significa “coloro che si sacrificano, s’immolano”. I fedayn sono a lungo sono stati considerati terroristi, anche se non proprio da tutti, ma in uno stadio è diventato sinonimo di irriducibili, intransigenti, devoti.

Potrebbe accadere lo stesso per i talebani: altro che insulto, presto forse sarà una qualifica che si rivendica in nome di una devozione e disciplina. E, visto che eravamo a Verona, magari allo stadio Bentegodi ci saranno i Talebani gialloblù – quasi l’apoteosi di questo viaggio linguistico, che nemmeno Ahmed Rashid avrebbe previsto.

Assolvendo l’imputato, la Corte decise di rilasciare il passaporto alla controverso epiteto, che può così meglio proseguire il suo viaggio nei linguaggi di altri popoli (anche se da usare con moderazione).

ENGLISH VERSION

The word ‘Taliban’ is a case that has made jurisprudence: meanings, nuances and ambiguities of a term that has entered our vocabulary.

Great travellers, the words. Some of them visit us from afar, some stay with us and begin to inhabit our dictionaries, we welcome them in our current language, or look at them with dismay, sometimes understandably, in the name of purity. There are extreme cases where these trips create havoc, even criminal trials. See the meaning of the word Taliban on the Treccani encyclopedia, on which I was questioned by the Military Tribunal of Verona in a story that has something of the films of our popular comedy. A story where travel together Afghanistan and Italy, the serious and the facetious, semantics and justice.

It all began with a phone call from a military chaplain: he had read some of my books on Afghanistan and told me about a soldier who chad an argument with a colleague and called him Taliban, getting sued for defamation.

But is Taliban an insult? So, I was requested, later also in a more formal way by a lawyer, to explain, as an expert on Afghanistan and its uses, the meaning of Taliban. It is not just a matter of dictionary, as, in another case, wrote on Rewriters Lorenzo Gasperrini, and perhaps one could start from a good bookon the Taliban, such as the ones by Ahmed Rashid (entitled Taliban) or by Peter Marsden (The Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan).

It was a bit of a hassle – getting to Verona at a certain time, for a hearing that started so late that I missed my flight home, all without any refund. Yet, it was also an exploration into both the intricacies of military justice, and in the journey of the offending word. The following “Short Memorandum on the Word and Concept of Taliban” was part of the official judiciary documents:

1) The word Talib is present in various Asian languages, and in the Afghan case it comes from the Pashtu vocabulary, where, as in Arabic or Persian, it means student. The word Taliban instead means students, both in Pashtu and in Persian, while in Arabic it is equivalent to two students. It is not aimed at a particular ethnic group, even if the Taliban are almost exclusively Pashtu, nor in the local parlance

2) In current practice, students are understood as students of religious, madras, or Koranic schools, given that in local traditions, schools were often managed by religious authorities, and that in any case, the curricula educational institutions respected and largely still respect religious precepts.

3) The word, therefore, does not in itself have any negative connotation. On the contrary, it can be synonymous with a disciplined, studious, methodical person. In any case, it is a term in current use in many countries.

4) However, the term Taliban also indicates a group of Islamic fundamentalists that has (as in other cases: Hamas, Hezbollah), both a civilian and a military branch. As it is known, the Taliban achieved power in almost all of Afghanistan from 1996 until the end of 2001. In their 1996 charter, one can read “our law is only in accordance with the Sharia of the prophet, without suffering, selfishness and oppression” – a reassuring mission statement.

In practice, however, the civilian power of the Taliban has expressed itself in some of the most barbaric and inhumane practices, with legislative and de facto structural discrimination against women, the practice of public stoning in stadiums, a ban on the possession of photographs and of practicing a certain number of professions or activities (such as fishing or the locally popular kite-flying). The term Taliban in this case becomes negative, as someone almost barbaric, backward, obscurantist.

5) Also, the Taliban have widespread insurgency activity in Afghanistan. They are engaged on two fronts: towards the Afghan government and armed forces, and towards the outposts that Daesh – or ISIS, or Islamic State – has managed to activate in the country.

In fact, the ideological platform and the political agenda of the Taliban are very different and almost opposite to those of ISIS (in summary terms: the Taliban, like Hamas or Hezbollah, are national and de facto ethnic entities, and repudiate terrorist activity abroad, while ISIS has an internationalist vision and also fights for the dismantling of existing Arab or Islamic states). This open conflict between the two groups led to the Taliban also receiving military aid from Russia, both anti-NATO and anti-ISIS).

6) Although this peculiar position makes the Taliban sometimes even allies of certain European policies, they are in any case enemies, both of the Afghan government and of the international coalition in its support, in which Italy also takes part. The term Taliban, in this case, can become particularly negative where it coincides with an enemy.

7) To make the position of the Taliban and indirectly the connotation of the term even more complex, these enemies are recognized as negotiating interlocutors in a peace deal launched under the aegis of the United States in Doha last year. Although the outcome of this discussion is uncertain (and I personally predict that it will not lead to results), through this official negotiation the Taliban acquire a recognized institutional role. The word Taliban once again fades into ambiguous meanings, since they might easily become part of a government coalition of a country fully recognized by Italy.

My name and a long list of references followed – my title of former Information Officer for the UN in Afghanistan, MEP member of the delegation for Afghanistan, current desk-officer for Afghanistan in the European Parliament as well as Head of Unit for Asia, and a large number of books and articles written on the theme. For the first time, my accurate competence would have contributed to making jurisprudence. What was at stake was both the outcome of the defamation, but also the possible customs clearance or the prosecution of the fateful word for future cases.

The debate with the judges and lawyers was not without interest, ranging from a report of my encounter with the Taliban to the Curva Sud of the Olimpico stadium in Rome. The latter was perhaps the definitive argument, because a historic ultras group of Giallorossi fans is called Fedayn, which in Arabic means “those who sacrifice themselves, immolate themselves”.

The fedayn have long been considered terrorists, even if not by all, but for the supporters what count is the meaning of hardcore, intransigent, devoted. The same could happen to the Taliban: other than an insult, perhaps soon it will be a qualification claimed in the name of devotion and discipline. And, since we were in Verona, I argued that perhaps the “Yellow-Blue Taliban” could soon be at the Bentegodi stadium – almost the apotheosis of this linguistic journey, which not even Ahmed Rashid would have expected.

By acquitting the defendant, the Court decided to issue the passport to the controversial epithet, which can thus better continue its journey in the languages of other peoples (albeit, use with moderation).