Padiglione Bulgaro alla Biennale di Venezia: la mostra sulle scuole abbandonate

Le fotografie del padiglione bulgaro: un viaggio nel cuore di un’Europa di vecchi dove la vecchia cara scuola è ormai inutile.

Le fotografie del padiglione bulgaro: un viaggio nel cuore di un’Europa di vecchi dove la vecchia cara scuola è ormai inutile.

(English translation below)

Negli ultimi trent’anni la popolazione della Bulgaria è diminuita del 38%, di quasi 900.000 persone solo dal 2010. E si prevede che nei prossimi trent’anni il declino demografico sarà di un ulteriore 22%.

Muta radicalmente anche la distribuzione: una persona su tre vive in una delle sei città principali, e solo il 26% in campagna. La Bulgaria declina con enfasi una realtà di buona parte dell’Europa, e parla per tutti noi: anche in Italia o in Spagna le cose sono così, tanto da imporre una strategia che finora manca (ne ho scritto recentemente per la Fondazione Ugo La Malfa).

C’è un aspetto materiale, visivo, paesaggistico, di questo spopolamento, e la Bulgaria lo scodella senza reticenze in uno dei più coraggiosi padiglioni nazionali alla Biennale di Architettura di quest’anno, dedicato all’andare in malora degli edifici scolastici, soprattutto nelle zone rurali, e alle (poche) idee per ridargli vita.

A vedere le oltre duecento fotografie di scuole abbandonate esposte nel padiglione bulgaro (e sono poche, a fronte delle 1.435 che hanno chiuso dal 1981), pare di guardare altrettanti vettori ormai obsoleti, viaggi di intere generazioni che come tutti noi sono entrati a scuola per uscirne trasformati anni dopo, luoghi che aprivano mille percorsi, allargavano i confini intellettuali ed emotivi, centri di identità di un villaggio e anche di apertura al resto del mondo.

Perché scuola è sempre stato uno dei sinonimi di viaggio. Ma la combinazione di spopolamento e urbanizzazione, ha ridotto queste architetture, così varie ma sempre inconfondibili (ci sono mille modi di costruire una scuola, ma sempre tale appare già a prima vista) a obsoleti aeroplani a reattore parcheggiati nel deserto, a navi da smantellare in qualche rada in necessità di bonifica.

Nessuno vi entra più, nessuno vi viaggia più, siamo forse un popolo di nomadi vecchi che non ha più bisogno di aule e palestre e di libri per coltivare i primi sogni.

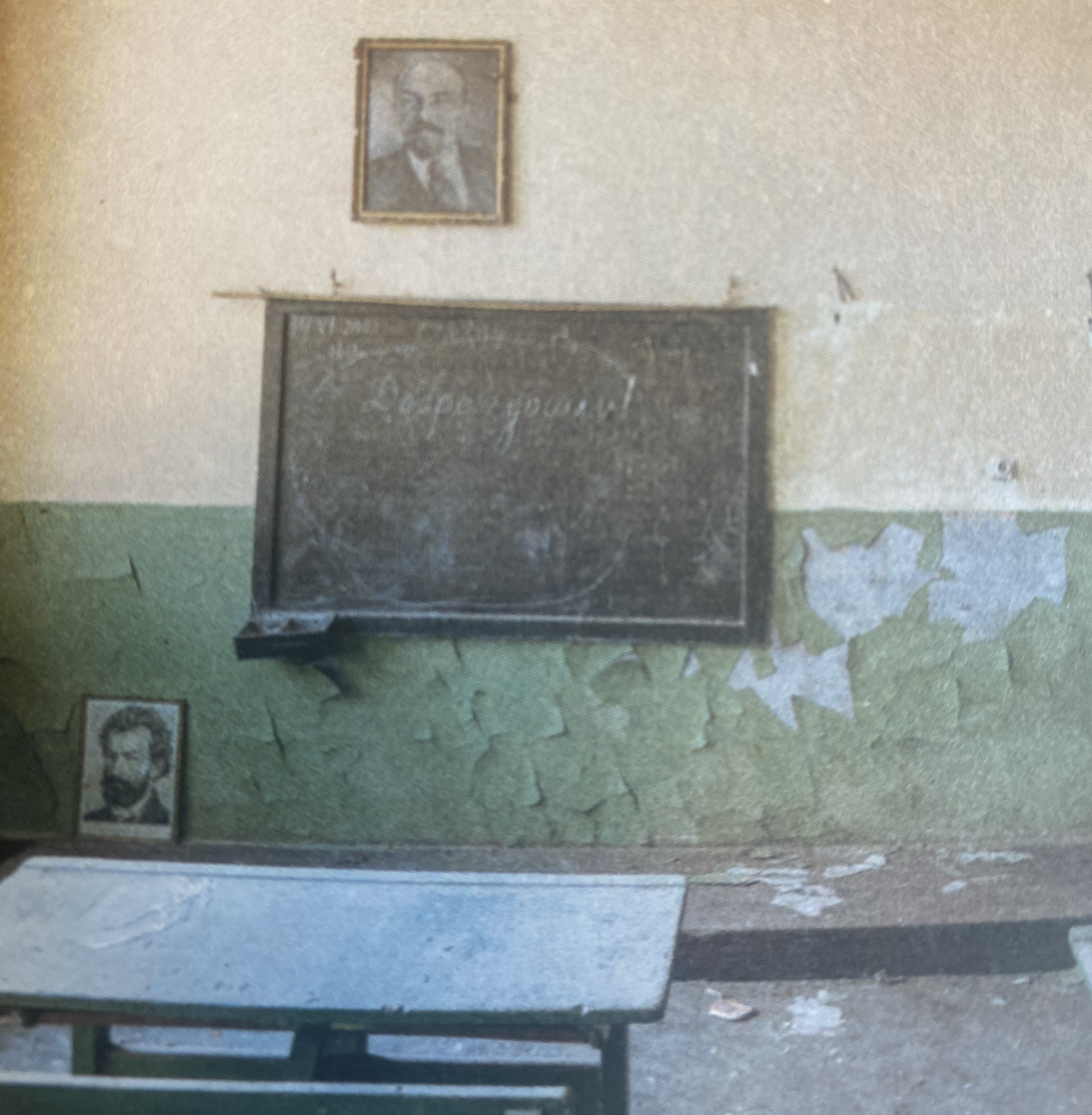

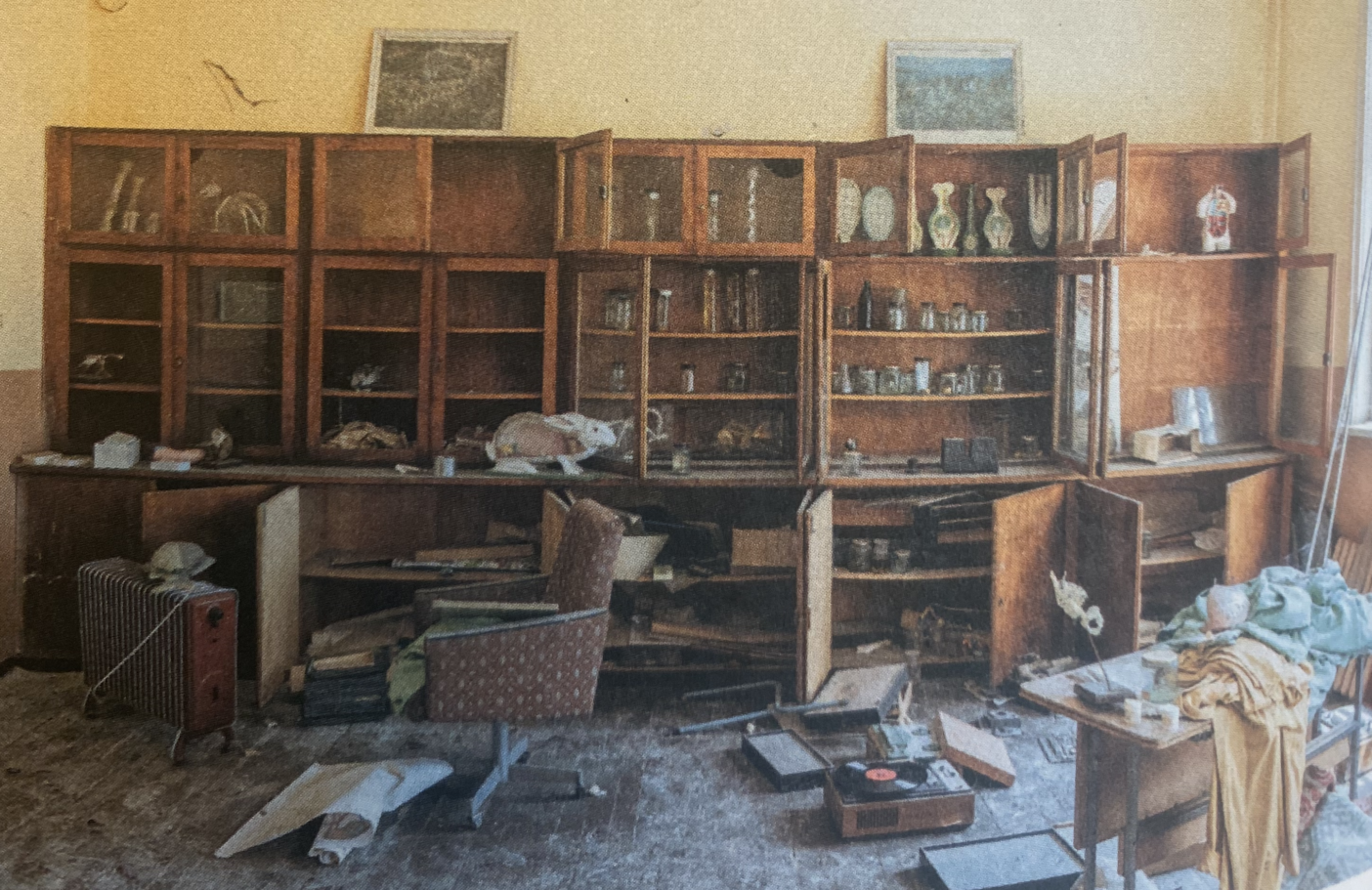

Restano solo calcinacci, topi, palloni sgonfi, reti da pallavolo cadenti, scaffali impolverati. Le fotografie del padiglione bulgaro sono un viaggio nel cuore di un’Europa agli sgoccioli e tutta al passato: una lavagna presenta ancora l’ultima lezione, restano appesi alcuni ritratti di Lenin, i materassini per gli esercizi di ginnastica sono mangiati dai roditori e si specchiano nei banchi abbandonati. Alle pareti, le frasi didattiche, gli schemi di biologia o le tabelle aritmetiche, sono segni nel vuoto.

Sprangate da fuori, marce dentro, queste scuole restano feticci di villaggi sempre più vuoti, musei di comunità in estinzione. Eppure sono luoghi di storia, e molto spesso anche architetture di valore. Che farne?

Il padiglione bulgaro raccoglie interviste, tutte testimonianze lucide e altrettanto coinvolgenti, di falegnami e architetti, educatori ed ex-studenti, e documenta moltissimi dati. Non giunge a vere proposte, non vara un piano d’azione, si limita, per ora, a documentare e a lanciare un dibattito, e a prenderci per mano in un’esplorazione di una giovinezza europea che non è più e che, anche architettonicamente, è una forma della nostalgia.

ENGLISH VERSION

The photographs of the Bulgarian pavilion are a journey into the heart of a Europe on its last legs, where the dear old school is now useless in a Europe of the old.

Over the last thirty years, Bulgaria’s population has decreased by 38%, by almost 900,000 people since 2010 alone. The population decline is expected to be a further 22% over the next thirty years. The distribution also radically changes: one out of three people lives in one of the six main cities, and only 26% in the countryside. Bulgaria emphatically declines the situation of a good part of Europe, it speaks for all of us: even in Italy or Spain things are like this, so much so as to impose a strategy that has been missing so far (I recently wrote about it for the La Malfa Foundation).

There is a material, visual, landscape aspect of this depopulation, and Bulgaria shows it without hesitation in one of the bravest national pavilions at this year’s Architecture Biennale, dedicated to the deterioration of school buildings, especially in rural areas, and the (few) ideas to bring them back to life.

Looking at the over two hundred photographs of abandoned schools on display (and those are few, compared to the 1,435 that have closed since 1981), it seems like we are looking at just as many obsolete “vectors”, journeys of entire generations who, like all of us, entered school to exit years later transformed, places that disclosed thousand paths, widened the intellectual and emotional boundaries, centers of identity of a village and also of openness to the rest of the world. “School” has always been one of the synonyms for “journey”. Yet, the combination of depopulation and urbanization has reduced these architectures, so varied but always unmistakable (there are a thousand ways to build a school, but it always appears as such at first sight) to obsolete jet airplanes parked in the desert, to ships to be dismantled in some harbour. Nobody enters there anymore, nobody travels there anymore: we are perhaps a population of old nomads who no longer need classrooms and gyms and books to cultivate our first dreams.

All that remains are rubble, mice, deflated balls, falling volleyball nets and dusty shelves. The photographs of the Bulgarian pavilion are a journey into the heart of a Europe that is entirely in the past: a blackboard still presents the last lesson, some left portraits of Lenin, the mats for gymnastic exercises are eaten by rodents and are reflected in the abandoned benches. On the walls, the didactic sentences, the biology diagrams or the arithmetic tables are signs in the void.

Barred from the outside, rotten from the inside, these schools remain fetishes of increasingly empty villages, museums of disappearing communities. Yet they are places of history, and very often also valuable architecture. What to do with it?

The Bulgarian pavilion collects interviews – all lucid and equally moving – with carpenters and architects, educators and former students, and documents a wealth of data. It does not come to operational proposals, it does not present an action plan, it limits itself, for now, to documenting and launching a debate. It rather take the visitor in an exploration of a European youth that no longer exists and which, even architecturally, is a form of nostalgia.