Nel centenario della morte, leggere Kafka come un viaggio oscuro

Uno degli aspetti più innovatori di Kafka è il ruolo irrequieto e di ribellione del viaggio. I libri "America", "Castello", Processo".

Uno degli aspetti più innovatori di Kafka è il ruolo irrequieto e di ribellione del viaggio. I libri "America", "Castello", Processo".

(English translation below)

Cento anni fa, nel 1924, il corpo di Franz Kafka ci ha lasciato. Ma è restata la sua opera, e col dopo-Kappa”non siamo più gli stessi: nella letteratura, nei libri che leggiamo, sono entrati un’alienazione inspiegabile, il senso di persecuzione, i labirinti di una società imperscrutabile dove la burocrazia è un quarto e oscuro potere, esistenze prive di Dio eppure segnate da un contorto anelito di spiritualità – e molto altro.

Incontrare i personaggi di Kafka implica aggirarsi per lunghi corridoi, in forme della melanconia, della disperazione e anche della volontà, che non sono mai statiche. Perché uno degli aspetti più innovatori di Kafka è il ruolo irrequieto e di ribellione del viaggio, il viaggio per sfuggire a qualcosa, spesso senza approdo – peraltro ripreso da Beckett (l’abbiamo visto dal tempo dei viaggi e degli abbandoni e a pensarci è anche sorprendente viaggiavano solo le vittime, in Com’è).

Kafka amava viaggiare, soprattutto per quella Mitteleuropea cosmopolita di cui amava il versante meridionale – Trieste, Venezia, Merano, e altre tappe si possono percorrere sul sito del Centro ceco di Roma e anche i suoi sogni prendevano la forma effimera del viaggio, a sua volta passaggio, come scrisse a Milena:

“La mia testa è come una stazione ferroviaria, treni partono, treni arrivano, visita doganale, l’ispettore superiore di frontiera guarda il visto, ma questa volta è regolare, ecco, guardi pure: “Sì, sta bene, di qui si esce dalla stazione”. “Scusi, signor ispettore superiore, vuole avere la cortesia di aprirmi la porta, non riesco ad aprire. Forse sono debole perché fuori c’è Milena che mi aspetta”. “Oh, scusi” esclama lui, “non lo sapevo.” E spalanca la porta…”

Un incubo legato al viaggio è anche Nella colonia penale, dove l’esploratore è il personaggio che arrivando da fuori deve testimoniare dell’atroce macchinario in cui condannato e ufficiale finiscono per scambiarsi i ruoli, una visita che si supera solo con una nuova partenza. Il viaggio è perfino rovesciato, come quello che, ancora una volta complesso, oscuro e portatore di sensi di colpa, compiuto dall’alto del trono, da un’inafferrabile lontananza, Il Messaggio dell’imperatore,

“inviato a te, singolo individuo, miserabile suddito, ombra minuscola fuggita dall’abbagliante sole imperiale nelle più remote lontananze, proprio a te ha inviato un messaggio dal suo letto di morte”.

Perfino l’innocua estetica dell’albergo – quello Dei signori ai piedi del Castello, l’Occidental in America – è animata dal perverso meccanismo delle porte girevoli, dalla claustrofobia atemporale degli ascensori, dalla struttura a corridoio e diramazioni di camere chiuse come altrettanti enigmi.

C’è in Kafka un’agitazione diffusa a vocazione terapeutica, eppure sempre fallimentare:

“per cercar di eliminare l’azione dei fantasmi tra uomo e uomo e per raggiungere il contatto naturale, la pace delle anime, (l’umanità) essa ha inventato la ferrovia, l’automobile, l’aeroplano, ma ciò non serve più, sono evidentemente invenzioni fatte durante il crollo; la parte avversaria è molto più calma e più forte, anche se l’umanità dopo la posta ha inventato il telegrafo, il telefono, il telegrafo senza fili. Gli spiriti non moriranno di fame, ma noi periremo.”

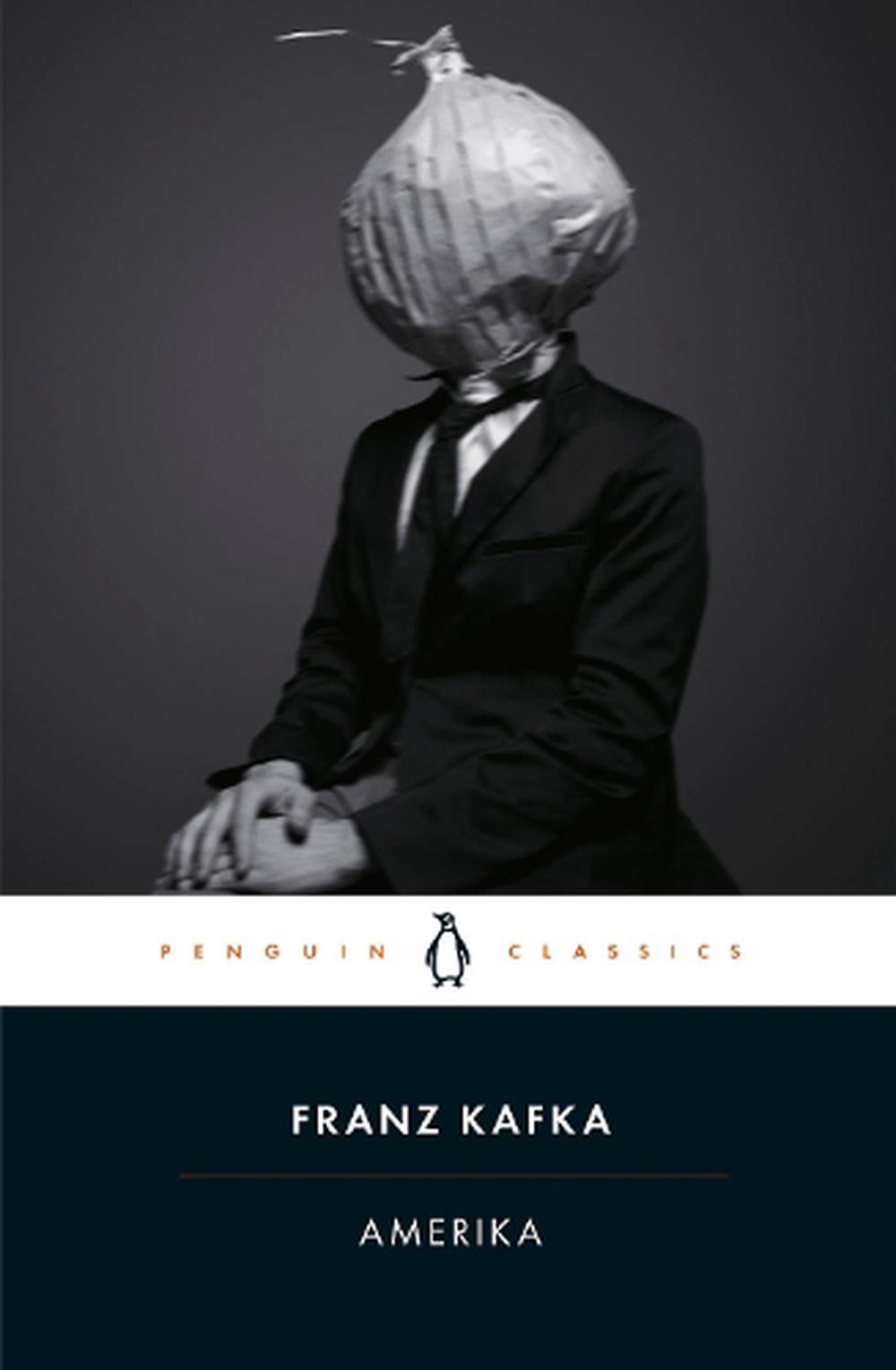

Il movimento è un vagito durante il crollo, funzionale a una redenzione, eppure non serve: proprio come in ciascuno dei romanzi, che possiamo leggere come capolavori di una letteratura di viaggio capovolta: il più esplicito è America, dove le peripezie del giovane protagonista vorrebbero farsi genesi – Le prime giornate di un europeo in America possono essere paragonate alla nascita di un uomo – e la cui conclusione, incompiuta, si elide nell’andare a lavorare per il Teatro Naturale di Oklahoma, un circo e dunque un viaggio alla seconda.

Anche l’agrimensore arriva da lontano e, non ammesso nel Castello, è costretto a dilatare il suo viaggio, e a non vederne mai l’approdo finale, confinato nell’osteria dove da straniero si relaziona con i locali. L’imputazione del Processo avvia una inesauribile peregrinazione di K tra uffici, sotterranei, corridoi di palazzi di giustizia, gabinetti di avvocati, visite a improbabili personaggi: la sua reclusione è proprio nell’assenza di una cella, di una sentenza, nel doversi districare senza pausa tra un miriade di passaggi – burocratici e non solo – che sono altrettante trappole.

L’apogeo del viaggio di e per Kafka, lo si ha nella parabola del questuante in attesa che il cancello si apra. Di lui sappiamo molto poco, ma è anche lui è un pellegrino e viene da lontano; e pare che per Kafka possa ambire a entrare nel Palazzo proprio in quanto viaggiatore:

“L’uomo che per il viaggio si è provvisto di molte cose dà fondo a tutto per quanto prezioso sia, tentando di corrompere il guardiano. Questi accetta ogni cosa ma osserva: “Lo accetto soltanto perché tu non creda di aver trascurato qualcosa”.

Il guardiano si rende conto che l’uomo è giunto alla fine e per farsi intendere ancora da quelle orecchie che stanno per diventare insensibili, grida.

“Nessun altro poteva entrare qui perché questo ingresso era destinato soltanto a te. Ora vado a chiuderlo”.

È il cerchio del viaggio la cui meta è la sua irraggiungibilità, l’apogeo della vanità del nostro cammino. Ecco che il viaggio diventa tutt’altro rispetto a scoperta, gloria, avventura, e non assume nessuno dei suoi aspetti gloriosi o maledetti cari alla letteratura del genere. No, il viaggio in queste opere diventa il tentativo doveroso ma fallimentare di risolvere l’enigma dell’esistenza e la sua fragilità intrinseca, l’irresistibile bisogno e anche l’inutilità di uscire dalla tana. Kafka: un compagno di strada che ci ha avvertito.

ENGLISH VERSION

One hundred years ago, in 1924, Franz Kafka’s body left us. But his work has remained, and in the post-K we are no longer the same: in literature, in the books, we read, an inexplicable alienation has entered, the sense of persecution, the labyrinths of an inscrutable society where bureaucracy is a fourth and dark power, existences devoid of God yet marked by a twisted longing for spirituality – and much more.

Meeting Kafka’s characters involves wandering along long corridors, in forms of melancholy, desperation and also of will, which are never static. Because one of the most innovative aspects of Kafka is the restless and rebellious role of the concept of journey: the journey to escape something, often without landing – an element taken up also by Beckett (we have seen it from the time of journeys and abandonments and when you think about it it is also surprising only the victims were traveling, in How it is).

Kafka loved travelling, especially through cosmopolitan Central European and notably its southern side – Trieste, Venice, Merano, and other Kafka’s Italian visits can be known on the website of the Czech Center in Rome.

Even his dreams took the ephemeral form of the journey, itself a passage, as he wrote to Milena:

“My head is like a railway station, trains leave, trains arrive, customs visit, the superior border inspector looks the visa, but this time it’s regular, well, look: “Yes, he’s fine, we leave the station from here.” “Sorry, Mr. Superior Inspector, would you be kind enough to open the door for me, I can’t open it. Maybe I’m weak because Milena is waiting for me outside.” “Oh, sorry,” he exclaims, “I didn’t know.” And he throws open the door…”

A nightmare linked to travel is also In the penal colony, where the explorer is the character who, arriving from outside, has to witness the atrocious machinery in which the condemned and the officer end up exchanging roles, a visit that can only be overcome with a new departure. The journey is even reversed, like the one which, once again complex, dark and full of guilt, was made from the throne, from an elusive distance, in The Emperor’s Message

“it has been sent to you, a single individual, a miserable subject, a tiny shadow who has escaped from the dazzling imperial sun into the most remote distances, he has sent a message to you from his deathbed”.

Even the harmless aesthetics of the hotel – the one Of the gentlemen at the foot of the Castle, the Occidental – is animated by their corridor structure and branches of closed rooms like so many enigmas, by the intriguing mechanism of the revolving doors, by the timeless claustrophobia of elevators, with.

In Kafka there is a widespread agitation with a therapeutic vocation, yet always unsuccessful:

“to try to eliminate the action of ghosts between man and man and to achieve natural contact, the peace of souls, (humanity) has invented the railway, the automobile, the airplane, but this is no longer useful, they are evidently inventions made during the collapse; the opposing side is much calmer and stronger, even if humanity after the post office invented the telegraph, the telephone, the wireless telegraph. The spirits will not starve, but we will perish.”

The movement is a cry during the collapse, functional to a redemption, yet it is of no use: just like in each of the novels, which we can read as masterpieces of an upside-down travel literature: the most explicit is America, where the vicissitudes of the young protagonist would like to become genesis – The first days of a European in America can be compared to the birth of a man – and whose conclusion, unfinished, is elide in going to work for the Oklahoma Natural Theater, a circus and therefore a trip to the second. Even the land surveyor comes from afar and, not admitted into the The Castle, is forced to extend his journey, and never see the final landing place , confined to the tavern where as a foreigner he relates to the locals.

The indictment of The Trial begins an inexhaustible wandering of K between offices, basements, corridors of courthouses, lawyers’ offices, visits to unlikely characters: his imprisonment is precisely in the absence of a cell, of a sentence, in having to extricate himself without pause from a myriad of “steps” – bureaucratic and otherwise – which are just as many traps.

The apogee of the journey by and for Kafka occurs in the parable of the beggar waiting for the gate to open. We know very little about him, but he is also a pilgrim and comes from afar; and it seems that for Kafka he may aspire to enter the Palace precisely as a traveler: “The man who has provided himself with many things for the journey gives up everything, however precious it is, attempting to bribe the guardian. He accepts everything but observes: “I accept it only so that you don’t think you have overlooked anything.”

The guardian realizes that the man has reached the end and to make himself heard again by those ears that are about to become insensitive, he shouts. “No one else could enter here because this entrance was meant only for you. Now I’m going to close it.”

This is the circle of the journey, whose destination is its unattainability, the apogee of the vanity of our journey. Here the journey becomes completely different from discovery, glory, adventure, and does not take on any of its glorious or cursed aspects so dear to the travel literature. On the contrary, the journey in these works becomes the dutiful but unsuccessful attempt to solve the enigma of existence and its intrinsic fragility, the irresistible need and also the futility of getting out of the den. Kafka: a fellow traveller who warned us.

1 Comment

In viaggio con Kafka, un appassionato attraversamento.

Grazie