“Las Kellys”, il movimento nato in Spagna per i diritti delle cameriere in hotel

E' il lato oscuro dell’umanità dei nostri viaggi: Las Kellys è un movimento per riscrivere il lavoro del personale di pulizia delle camere d’albergo.

E' il lato oscuro dell’umanità dei nostri viaggi: Las Kellys è un movimento per riscrivere il lavoro del personale di pulizia delle camere d’albergo.

(English translation below)

C’è un personaggio centrale nella vita del viaggiatore, eppure destinato a restare nell’ombra. Ogni giorno lo incrociamo, ogni volta lo ignoriamo. Anonimo, mai ne conosciamo il nome. A volte è l’unico che si prende cura del viaggiatore, e lo fa ogni giorno, ma di norma è trattato come se non esistesse, restando nell’ombra, escluso dalle vicissitudini del viaggio dagli incontri, dalle conversazioni.

E così deve essere, perché la sua invisibilità ne è un tratto costitutivo. Questa creatura misteriosa si occupa direttamente e materialmente del benessere del viaggiatore, del suo ordine e della sua pulizia, ma sono compiti come dati per scontati e sui quali il viaggiatore non si sofferma.

È l’unica persona lasciata addirittura sola tra quelle poche cose care – vestiti, libri, appunti, oggetti per la pulizia – che il viaggiatore si porta con sé nel suo nomadismo e alle quali affida la continuità di un mondo personale, della sua casa mobile.

Una capacità di varcare la soglia di una certa intimità che permette l’accesso anche a computer rimasti in albergo, appunti di lavoro, documenti: e non a caso, come ben sa il diplomatico, in alcuni Paesi questo personaggio sfuggente è anche un informatore, una vera e propria spia, che predispone pulci, prende fotografie, sa dove guardare tra i nostri fogli, anche quelli che in un gioco a rimpiattino lasciamo apposta con agende e nomi predisposti per depistare e mescolare le carte – i mezzucci del mestiere.

Quasi sempre ha le sembianze di una donna curata e pulita, silenziosa, dalle movenze felpate e ripetitive, spesso giovane – e ne ho incontrate di bellissime. Eppure il viaggiatore, qualora lo incontri, dedica a questo personaggio un frettoloso saluto, due parole talvolta come reticenti e imbarazzate.

È il più ignorato e negletto degli angeli custodi, relegato agli ultimi gradini della scala sociale e di quella dei nostri incontri di viaggiatori. Di questa figura quasi mitica non ricordo un solo caso di qualcuno che, al ritorno delle sue peregrinazioni, ne abbia mai parlato, nessuno scrittore di viaggi che vi abbia dedicato un solo rigo.

È il destino delle donne delle pulizie degli alberghi, di cui non sappiamo niente – mentre delle domestiche a casa in genere sappiamo tutto. Al centro del paradiso dei nostri viaggi – siano favolose città da scoprire o luccicanti resort di mare all inclusive – il loro è spesso un inferno: nessun opuscolo turistico spende una parolina per descrivere le condizioni di lavoro del personale di camera, che in un giorno può percorrere anche 17 chilometri, piegarsi migliaia di volte in compiti che nulla hanno di ergonomico e che quasi sempre alla lunga provocano dolori muscolari e artriti, maneggiare di continuo prodotti tossici, restare giorni interi in ambienti con sola aria condizionata.

Persone che spesso alloggiano in locali sotterranei, talpe dei nostri alberghi di lusso, lontane da casa per trasferte che durano stagioni intere, con orari e giorni di riposo a volte arbitrari. Sfruttamento? In alcuni Paesi sì; e quasi ovunque bassissima tutela sindacale: il rovescio dell’industria del benessere di chi parte – e non ci s’illuda che il boutique hotel del viaggiatore sofisticato abbia credenziali migliori rispetto alle grandi catene del turismo di massa.

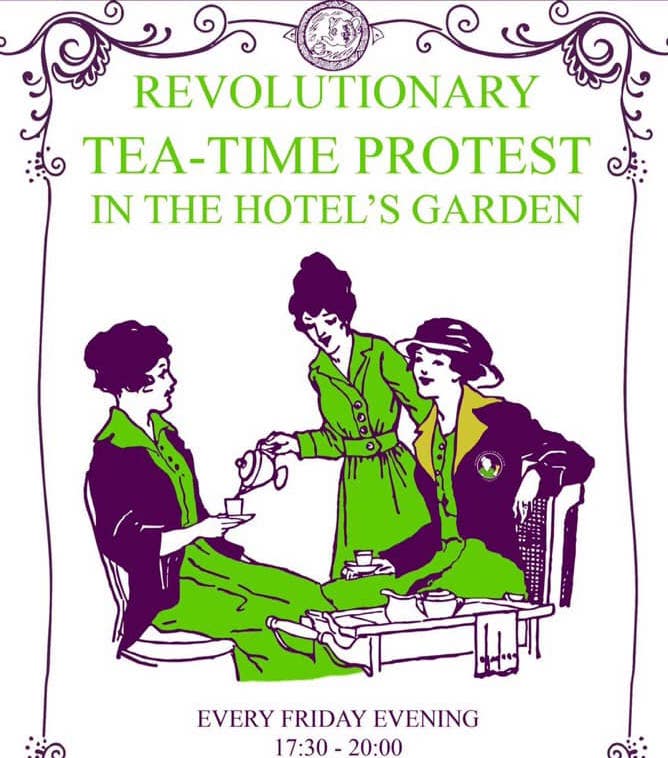

A questo ultimo gradino della prospera industria turistica, in Catalogna e soprattutto alle Baleari, è stato dedicato un movimento di riscatto per dargli visibilità, Las Kellys – che viene da las que limpian ovvero quelle che puliscono.

Ecco il viaggio predisposto al viaggiatore che fin qui ha ignorato queste donne che non è degno chiamare serve ma che spesso come tali sono trattate: è un percorso di video, libri, siti, installazioni – come l’inaugurazione, a Palma di Maiorca, di un’effimera Placa de la Kellys.

Al Parlamento Europeo è arrivata una mostra. Si sono stampate cartoline da affrancare e spedire che sono l’altra faccia della Luna dei nostri viaggi: le fotografie di queste cameriere, per una volta ridenti e riconosciute.

C’è rivendicazione di visibilità e di diritti nel movimento Las Kellys, ma anche gioia, umanità. Merito alle Baleari per questo progetto sorprendente, ma Las Kellys meritano di espandersi a movimento europeo.

Potrebbe essere la sorpresa dei nostri viaggi: scoprire i loro volti, parlare con loro anche brevemente ma con un’attenzione mai avuta finora, incontrarle, proprio con quel rispetto e quella curiosità umana che riserviamo agli incontri del nostro nomadismo.

Forse ne scaturirà qualcosa di inaspettato e di umano, come testimonia Guido Ceronetti, che sapeva pensare e scrivere quanto viaggiare, nel suo La pazienza dell’arrostito:

“Lasciata in albergo busta con denaro per il servizio, trovo rientrando in camera un pezzetto di carta con sopra tremante: Il personale ringrazia. Non mi era mai avvenuto”.

Ancora oltre, ma parliamo di geniali eccezioni più uniche che rare, si è spinta Sophie Calle con una delle sue estreme provocazioni: a Venezia si è fatta assumere come donna delle pulizie di un albergo per poter intrufolarsi nelle camere ed esplorare il mondo segreto dei clienti.

Ne ha ricavato The Hotel, un libro rivelatore e rovesciatore: siamo noi esploratori a essere esplorati da chi si aggira lecitamente nelle nostre camere di passaggio, siamo noi viaggiatori l’oggetto di altri viaggi. Proviamo a metterla così.

ENGLISH VERSION

It’s the dark side of humanity in our travels: Las Kellys is a movement to rewrite the job of hotel room cleaning staff.

There is a central character in the traveller’s life, yet destined to remain in the shadows. Every day we meet this anonymous “somebody”, every time we ignore him and have no idea about his name. Sometimes he is the only one who takes care of the traveller, and does it every day, but usually is treated as if doesn’t exist, remaining in the shadows, excluded from the vicissitudes of the journey, from meetings, from conversations. And so it must be, because his “invisibility” is a constitutive trait. This mysterious creature directly and materially takes care of the traveller’s well-being, his “order” and his cleanliness, but they are tasks taken for granted and on which the traveller does not dwell. He is the only person left even alone among those few dear things – clothes, books, notes, cleaning items – that the traveller takes with him in his nomadism and to which he entrusts the continuity of a personal world, of his exported home. An ability to cross the threshold of a certain intimacy that also allows access to computers left in the hotel, work notes, documents: and it is no coincidence that, as the diplomat well knows, in some countries this elusive character is also an informer, a real spy, who prepares fleas, takes photographs, knows where to look among our sheets, even those that we leave on purpose in a game of hide-and-seek with diaries and names prepared to mislead and shuffle the cards – the little professional tricks.

She almost always has the appearance of a well-groomed and clean woman, silent, with soft and repetitive movements, often young – and I met some quite beautiful. Yet the traveller, whenever he meets him, dedicates a hasty greeting to this character, two words that are sometimes reticent and embarrassed. He is the most ignored and neglected of the guardian angels, relegated to the bottom rungs of the social ladder and that of our travellers’ encounters. Of this almost mythical figure I don’t remember a single case of someone who, on the return of his wanderings, ever spoke of him, no travel writer who dedicated a single line to him.

He is the fate of the “maids” of hotels, of whom we know nothing – while of the maids at home we generally know everything. At the center of the paradise of our travels – whether fabulous cities to discover or glittering “all inclusive” seaside “resorts” – theirs is often a hell: no tourist brochure, perhaps verbose on the quality of the food offered and the chefs, spends a word to describe the working conditions of the room staff, who can travel up to 17 kilometers a day, bend over thousands of times in tasks that have nothing ergonomic about them and which almost always in the long run cause muscle pain and arthritis, constantly handle toxic products, stay whole days in rooms with air conditioning only. And often living in underground rooms, moles of our luxury hotels, far from home for entire seasons, with sometimes limited hours and days of rest. Exploitation? In some countries yes; and almost everywhere very low union protection: the reverse of the well-being industry for the guests – and no illusion that boutique hotels for more sophisticated travellers have any better credential than the large mass tourism chains.

To this last step of the prosperous tourist industry, in Catalonia and notably in the Balearic Islands, a redemption movement has been dedicated to give it visibility, “Las Kellys” – which comes from “las que limpian” “those who clean”. Here is the journey prepared for the traveller who has so far ignored these women who it is not worthy to call “servants” but who are often treated as such: it is a path of videos, books, websites, installations – such as the inauguration, in Palma de Mallorca, of an ephemeral “Placa de la Kellys”. An exhibition has arrived at the European Parliament. Postcards have been printed to be stamped and sent that are the other side of the moon of our travels: the photographs of these waitresses, laughing and recognized for once. There is assertiveness in claiming for visibility and rights, but there is also joy, human richness.

Credit to Balearic for this courageous project. Las Kellys would deserve of evolving in a European effort. It could be the surprise of our travels: discovering their faces, speaking to them even briefly but with attention never experienced before, meeting them, precisely with that respect and human curiosity that we reserve for the encounters of our nomadism. Perhaps something unexpected and human will emerge from it, as Guido Ceronetti testifies, who knew how to think and write as much as travel, in his The patience of the roasted one: “Left the envelope with money for the service in the hotel, I find on returning to the room a of paper with trembling on top: The staff thanks. It’s never happened to me.”

Even further, but we are talking about more unique than rare ingenious exceptions, Sophie Calle went with one of her extreme provocations: in Venice, she got hired as a cleaning lady in a hotel to be able to sneak into the rooms and explore the secret world of the customers. She wrote a revealing book, The Hotel, out of it: it is we explorers who are explored by those who roam lawfully in our passage rooms, we travellers are the object of other journeys – let’s try to put it like that.