Non due popoli due Stati ma una umanità uno Stato

Contro tutti i nazionalismi, il Manifesto di Ventotene è una lettura attuale e illuminante per la soluzione del conflitto in Medio Oriente.

Contro tutti i nazionalismi, il Manifesto di Ventotene è una lettura attuale e illuminante per la soluzione del conflitto in Medio Oriente.

(English translation below)

“Se vuoi conoscere le cause del passato guarda gli effetti del presente; se vuoi conoscere gli effetti del futuro, guarda le cause del presente”, Nichiren Daishonin (1253-1282)

Nell’ora più buia è un imperativo categorico per le persone di buona volontà, per la società civile, per la comunità accademica offrire nuovi orizzonti ad una realtà che sembra senza futuro e senza vie di uscita.

L’orrendo attacco perpetrato direttamente e intenzionalmente ai danni della popolazione civile di Israele il 7 ottobre scorso da parte dell’organizzazione Hamas è inequivocabilmente un attacco terroristico su larga scala come definito nei trattati internazionali e certamente un crimine contro l’umanità che offende il senso comune e le leggi internazionali sui diritti umani.

Esso non può in alcun modo configurarsi come un’azione legittima a favore dei diritti del popolo palestinese, mentre evidenzia in modo assolutamente chiaro l’intento di mettere in pratica l’eliminazione violenta dello stato di Israele e dei suoi abitanti, come del resto esplicitamente scritto nell’atto costitutivo di Hamas.

Non esiste e non può esistere per esso alcuna giustificazione storica né tantomeno morale, nonostante le evidenti responsabilità dello Stato di Israele e della comunità internazionale nell’aver ostacolato il processo di pieno di riconoscimento e autonomia dello Stato palestinese, secondo quanto previsto dagli accordi internazionali e ripetutamente richiesto dall’ONU con la Resolution 2334 del 2016 adottata dal Consiglio di Sicurezza.

Non può stupire dunque che il presente sia dominato, non solo per le élite politiche, ma anche per la stragrande maggioranza dei cittadini israeliani – siano essi di tradizione ebraica o araba, progressisti o conservatori, religiosi o atei, a favore o non a favore della causa palestinese – dalla necessità di proteggersi rispondendo sul campo ad Hamas che, con evidenti complicità internazionali, si trova ad essere ancora molto ben armato e ben posizionato, oltreché ancora con più di 200 ostaggi.

Ed è altrettanto chiaro che tale risposta, con le migliaia di vittime civili ed il dramma umanitario che ha già causato e causerà alla popolazione della striscia di Gaza, al di là degli eventuali successi militari, inevitabilmente sarà causa di ulteriore odio e rancore, soprattutto nelle nuove generazioni palestinesi che diverranno dunque terreno fertile per fare attecchire ulteriormente l’ideologia nazionalista e della distruzione fisica di Israele e dei suoi abitanti.

Una risposta che dunque darà agio, a quelle fazioni in Israele che non hanno mai voluto veramente l’indipendenza dei Territori, come evidente dall’assassinio nel 1995 del Primo Ministro Yitzhak Rabin promotore degli accordi di Oslo per mano di un estremista di destra, a proseguire indefinitamente in questa politica, giustificandosi con la reale minaccia che da quei territori continuerà a provenire.

E così via.

Purtroppo, di fronte a tale dramma, il dibattito attuale in Italia e nel mondo, non solo nelle piazze, ma anche in ambito politico, negli organi di informazione, nelle scuole e nelle università sembra più che altro la reazione viscerale e settaria di fazioni alla ricerca, nella infinita concatenazione di cause e di effetti che hanno portato a questo terribile presente, di giustificazioni per la medesima concatenazione di cause e di effetti da perpetrare nel futuro, imprigionando qualunque pensiero di pace.

Triste esempio ne è l’uso della conta delle vittime civili israeliane e palestinesi e del grado di atrocità con cui esse vengono mietute oggi e nel passato, alla ricerca di una giustificazione per la propria faziosità, piuttosto che come elemento di sgomento che serva a fare un salto di qualità nel modo in cui anche da qui possiamo sostenere un percorso di pace.

Al contrario una rigorosa ricerca storica delle cause e degli effetti dovrebbe essere utilizzata solo per identificare quali siano le strade possibili per la risoluzione del conflitto, scartando onestamente le vie fallimentari già percorse, identificando altrettanto consapevolmente i possibili punti di svolta che ancora non siano stati esperiti.

Le parti o, meglio, i rappresentanti istituzionali delle parti che si sono susseguiti negli anni, hanno già dimostrato, a torto o a ragione, di non volere o di non potere perseguire la strada della mediazione e delle inevitabili rinunce che la via della trattativa e del compromesso richiedono, rendendo di fatto oggi obsoleta la strada dei due Popoli due Stati ricercata con gli accordi internazionali e mai realizzata, nonostante le reiterate risoluzioni dell’ONU in materia.

Sarebbe oggi il caso che le persone nella società civile, invece di prendere parte al conflitto difendendo le ragioni dell’una o dell’altra parte sulla base di quanto accaduto, si sforzino di guardare oltre e trovare una soluzione alternativa a quella dei due Popoli due Stati, che sia orientata al valore della vita umana, alla cultura del rispetto e della valorizzazione delle differenze, siano esse etniche, culturali o religiose, oltreché personali, e che dia vita ad una nuova stagione che, sebbene utopica, serva da indirizzo nuovo, tanto quanto l’utopia dei due Popoli due Stati è stata sin oggi, evidentemente, il faro che ha guidato l’emersione del peggior nazionalismo.

Mi è del tutto evidente, che la linea di demarcazione tra ciò che è giusto e ciò che è sbagliato non si identifichi su base nazionale, né su base religiosa, né etnica, né che passi per un confine geografico, mentre la dottrina dei due Popoli due Stati, che forse ha avuto un tempo per potersi realizzare, ha di fatto consolidato sul campo l’idea identitaria che distingue gli ebrei e gli arabi e con essa il presunto diritto ad occupare luoghi geografici con strutture statali proprie.

Questa medesima declinazione dell’identità culturale alimentò nel corso del XIX secolo i grandi movimenti europei indipendentisti e repubblicani che, pur spesso di iniziale ispirazione democratica, si trasformarono altrettanto spesso in movimenti nazionalisti.

Questa traslazione dall’identità culturale all’identità nazionale è poi stata una delle matrici che hanno portato nel XX secolo alla Prima e poi alla Seconda guerra mondiale, quando al tema dell’identità nazionale si è aggiunta la spesso contigua idea della superiorità nazionale.

Tra i principali avversari della visione nazionalista in favore dello spostamento dell’enfasi ai temi della giustizia sociale ed economica, crebbero contestualmente i movimenti internazionalisti di ispirazione anarchica, socialista e comunista, ma qui desidero richiamare invece la posizione che ebbe un nostro padre nobile costituente, Alcide De Gasperi, rispetto alla Prima guerra mondiale.

De Gasperi nacque nel Trentino che apparteneva all’Impero asburgico e ne divenne deputato eletto come rappresentante delle popolazioni trentine nel 1911 al Parlamento austriaco di Vienna e nel 1914 alla Dieta tirolese di Innsbruck.

Fu più volte avvicinato da alti rappresentanti del governo italiano in cerca di appoggio alla guerra che l’Italia si apprestava a muovere all’Austria per ragioni nazionaliste (oltreché opportunistiche), che però rifiutò decisamente, convinto che il benessere delle popolazioni italiane non dipendesse dal nome dello Stato a cui appartenevano o sarebbero appartenute, ma dalla forma costituzionale di quello stato e dalla loro capacità di difendere i propri diritti.

Una simile visione, seppur da presupposti culturali differenti rispetto a quelli degasperiani, si ritrova nel Manifesto di Ventotene del 1941 di Altiero Spinelli ed Ernesto Rossi, dove la tragedia ancora non pienamente consumata della Seconda guerra mondiale, causata dalle ideologie nazionaliste, diventa la motivazione per una visione nuova che vuole superare il male dei nazionalismi ottocenteschi e novecenteschi e la loro inevitabile attrazione per la guerra. Il seguente passaggio ne è espressione evidente e illuminata:

“La linea di divisione fra partiti progressisti e partiti reazionari cade perciò ormai non lungo la linea formale della maggiore o minore democrazia, del maggiore o minore socialismo da istituire, ma lungo la sostanziale nuovissima linea che separa quelli che concepiscono come fine essenziale della lotta quello antico, cioè la conquista del potere politico nazionale — e che faranno, sia pure involontariamente, il gioco delle forze reazionarie lasciando solidificare la lava incandescente delle passioni popolari nel vecchio stampo, e risorgere le vecchie assurdità — e quelli che vedranno come compito centrale la creazione di un solido stato internazionale, che indirizzeranno verso questo scopo le forze popolari e, anche conquistato il potere nazionale, lo adopreranno in primissima linea come strumento per realizzare l’unità internazionale”

E ancora, oltreoceano, le medesime aspirazioni si percepiscono nel concetto di cittadinanza globale (chikyu minzokushugi) concepito nell’immediato dopoguerra da Josei Toda – uno dei pochi oppositori del regime nazionalista giapponese e per questo messo in carcere dal 1943 al 1945 – per offrire un nuovo ideale cui tendere e per superare definitivamente il male del nazionalismo.

Ecco qui che lo spartiacque che nasce dalla tragedia della Seconda guerra mondiale è superare i nazionalismi e forse addirittura il concetto stesso di nazione, eliminando o rendendo morbidi i confini piuttosto che istituirne di nuovi e ideando una forma organizzativa statale che serva a gestire il vivere comune indipendentemente da qualunque differenza culturale, religiosa, etnica, personale.

Ne sono figlie illustri la nostra Costituzione, l’istituzione sebbene incompiuta della Comunità Europea e anche quella altrettanto incompiuta dell’Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite.

Paradossalmente invece la stessa ONU con la Risoluzione 181 del 1947 pianifica l’istituzione di nuove frontiere definendo nella Parte I, sezione B, comma 3 che “shall proceed to carry out measures for the establishment of the frontiers of the Arab and Jewish States” [trad. bisogna procedere a portare avanti le misure per stabilire le frontiere degli stati Arabo e Ebraico], sancendo che una nuova linea di demarcazione avrebbe da allora per sempre diviso esseri umani in base alla loro appartenenza religiosa o etnica ed ispirandoli da allora a perseguire quella visione.

Non è mio compito entrare nel merito delle ragioni storiche che portarono a tale risoluzione, ma il risultato è oggi sotto gli occhi di tutti e dovrebbe esserne riconosciuto il fallimento, mettendo al centro del progetto futuro un nuovo orizzonte ideale cui tendere, invece di insistere nell’errore.

Forse è giunto il tempo di tornare allo spirito che dopo la Seconda guerra mondiale animò le menti più illuminate e che identificò nel nazionalismo il male da superare.

Se pensiamo alle bambine e ai bambini che stanno nascendo in questo preciso momento nella terra che oggi chiamiamo Israele e Palestina, è certo che nessuna e nessuno di loro ha contezza della nazione in cui sta nascendo, né della religione che praticherà, né di qualunque altra personale peculiarità svilupperà nel corso della vita.

Uno stato moderno dovrebbe solo accogliere questa inconsapevolezza di nascita facendo in modo che le opportunità con cui quelle bambine e quei bambini potranno accedere al loro sviluppo personale e sociale siano indipendenti dai loro caratteri psico-somatici, incluse le eventuali disabilità, dalle religioni che praticheranno, dalle tendenze politiche, dalle possibilità economiche e così via.

Uno stato di questa natura non ha senso che sia chiamato né ebraico né arabo.

In questo senso, tutte le colpe che si sono susseguite sino ad oggi sono purtroppo figlie forse inevitabili di un grande abbaglio, di un enorme errore commesso quando alla fine della Seconda guerra mondiale si è continuato a pensare per questa terra un futuro su base nazionale identitaria, che era proprio ciò che aveva causato la guerra, invece che ideare per essa un nuovo modo di stare insieme.

Solo sulla comune consapevolezza di essere stati indotti in errore dall’approccio nazionalista all’origine si potranno, se non cancellare, almeno comprendere le colpe passate e presenti perpetrate dall’una e dall’altra parte e fondare una nuova convivenza che non sia quella forzosa del vincitore sui vinti e per la quale la memoria non sia imperitura origine di odio reciproco e di conflitto.

Perché prima o poi, per convivere, bisognerà anche perdonarsi.

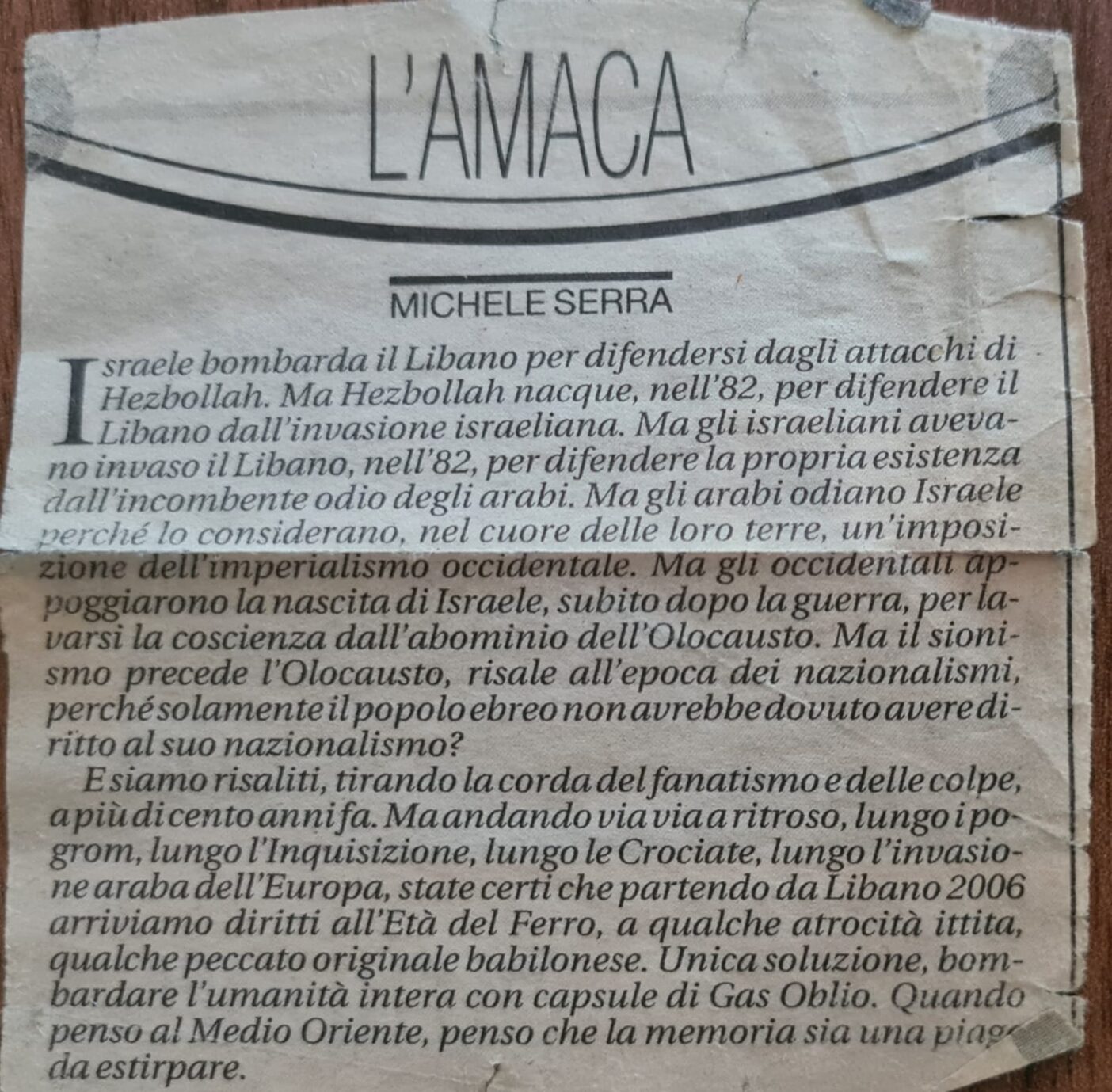

Forse, se questa nuova utopia inizia a viaggiare, se non oggi, un domani potrà realizzarsi e finalmente il popolo di quella terra, ebrei e arabi insieme e insieme a chiunque altro là deciderà di migrare, potrà vivere e proteggersi come appartenente alla stessa umanità, nello stesso stato laico e democratico. Vi lascio con una ispirata e attualissima Amaca di Michele Serra pubblicata nel 2006 su la Repubblica.

ENGLISH VERSION

One humanity, One state. Against all nationalisms, the Ventotene Manifesto is still a contemporary and enlightening read

“If you want to understand the causes that existed in the past, look at the results as they are manifested in the present. And if you want to understand what results will be manifested in the future, look at the causes that exist in the present”. Nichiren Daishonin (1253-1282)

In the darkest hour, it is a categorical imperative for people of goodwill, for civil society, for the academic community to offer new horizons to a reality that seems without a future and with no way out.

The horrendous attack perpetrated directly against the civilian population of Israel on October 7th by the Hamas organization is unequivocally a large-scale terrorist attack according to international treaties and certainly, a crime against humanity that offends common sense and international human rights laws. It cannot in any way be configured as a legitimate action in favor of the rights of the Palestinian people, while it highlights in an absolutely clear way the explicit intent to implement the violent elimination of the state of Israel and its inhabitants, as clearly stated in the Hamas Charter since 1988. There is and cannot be any historical or moral justification for it, despite the obvious responsibilities of the State of Israel and of the international community in having hindered the process of full recognition and autonomy of the Palestinian State, as provided for by the international agreements and several UN resolutions.

It is therefore not surprising that the present is dominated, not only by the political elites, but also for the vast majority of Israeli citizens – be they of Jewish or Arab tradition, progressive or conservative, religious or atheists, in favor or not in favor of the Palestinian cause – by the need to protect themselves by responding on the field to Hamas which, with evident international complicity, still finds itself very well armed and well positioned, as well as still holding over 200 hostages.

And it is equally clear that this response, with the thousands of civilian victims and the humanitarian drama that it has already caused and will cause to the population of the Gaza Strip, beyond any military successes, will inevitably be the cause of further hatred and resentment, especially in new Palestinian generations who will therefore become fertile ground for the nationalist ideology and the physical destruction of Israel and its inhabitants to further take ground.

And which will therefore give the opportunity to those factions in Israel who have never really wanted the independence of the Territories, as demonstrated by the killing in 1995 of the Prime Minister Mr. Rabin promoter of the Oslo Accord, to continue this policy indefinitely, justified by the real threat that will continue to come from those territories.

And so on.

Unfortunately, the current debate on such a disaster, in Italy, and in the world, not only in the streets but also in the political sphere, in the media, in schools, and in universities seems more like the visceral and sectarian reaction of factions in search, in the infinite concatenation of causes and effects that have led to this terrible present, of justifications for the same concatenation of causes and effects to be perpetrated in the future, imprisoning any thought of peace.

A very sad example is the use of the count of Israeli and Palestinian civilian victims and the degree of atrocity with which they are killed today and in the past, in search of a justification for one’s own bias, rather than as an element of dismay that serves to a qualitative leap in the way in which we can support a path of peace.

On the contrary, rigorous historical research into the causes and effects should only be used to identify the possible paths for resolving the conflict, honestly discarding the failed paths already taken, and equally consciously identifying the possible turning points that have not yet been experienced.

The parties or, rather, the institutional representatives of the parties over the years, have already demonstrated, rightly or wrongly, that they do not want or are unable to pursue the path of mediation and the inevitable sacrifices that the path of negotiation and compromise require, effectively making obsolete the Two Peoples Two States path sought through international agreements and never realized, despite the repeated UN resolutions on the matter.

It would be the time that people in civil society, instead of taking part in the conflict by defending the reasons of one or the other party on the basis of what happened, would strive to look beyond and open the sight to new hypotheses to settle the conflict and see the light of convivence at the end of the tunnel, oriented to the value of human life, to the culture of respect and valorization of differences, be they ethnic, cultural or religious, as well as personal, to give life to a new season which, although “utopian”, may serve as a new direction, just as the utopia of the Two Peoples Two States has evidently been up to now the beacon that has guided the emergence of the worst nationalisms.

It is completely clear to the writer that the line of demarcation between what is right and what is wrong is not identified on a national basis, nor on a religious or ethnic basis, nor does it pass through a geographical border, while the doctrine of the Two Peoples Two States, which perhaps had its time to be realized, has in fact consolidated the idea of identity that distinguishes the Jews and the Arabs and with it the presumed right to occupy different geographical places with different statal structures.

This same declination of cultural identity fueled the European independence and republican movements during the 19th century which, although often initially democratic in inspiration, just as often transformed into nationalist movements.

This translation from cultural identity to national identity was one of the factors that led in the 20th century to the First and then the Second World War, when the often-contiguous idea of national superiority was added to the theme of national identity.

Among the main opponents of the nationalist vision in favor of shifting the emphasis to the themes of social and economic justice, the internationalist movements of anarchist, socialist and communist inspiration grew at the same time, but here I would like to recall instead the position held by one of our noble constituent fathers, Alcide De Gasperi, at the time of the First World War. De Gasperi was born in Trentino which belonged to the Austrian Empire and became a deputy elected as representative of the Trentino population in 1911 at the Austrian Parliament in Vienna and in 1914 at the Tyrolean Diet of Innsbruck.

He was approached several times by high representatives of the Italian government seeking support for the war that Italy was preparing to wage against Austria for nationalist (as well as opportunistic) reasons, which he however decisively refused, convinced that the well-being of the Italian population did not depend on the name of the state to which they belonged or would have belonged, but by the constitutional form of that state and their ability to defend their rights. A similar vision, albeit from different cultural assumptions compared to De Gasperi’s, is found in the 1941 Ventotene Manifesto by Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi, where the still not fully consummated tragedy of the Second World War, caused by nationalist ideologies, becomes the motivation for a new vision that wants to overcome the evil of nineteenth- and twentieth-century nationalisms and their inevitable attraction to war. The following passage is a clear and enlightened expression of this:

“The dividing line between progressive and reactionary parties no longer coincides with the formal lines indicating a more or less advanced democracy, a more or less developed form of socialism, but rather with a very new, substantial line: on one side are those who see the old objective of struggle, in other words, the conquest of national political power, and who will, albeit involuntarily, play into the hands of the reactionary forces, by allowing the incandescent lava of popular passions to set in the old moulds with past absurdities resurfacing, while on the other side are those who see their main duty as the creation of a solid international state, who will direct popular forces towards this goal, and who, even if they gain national power, will use it above all as an instrument to bring about international unity. “

And again, overseas, the same aspirations are perceived in the concept of global citizenship (chikyu minzokushugi) conceived in the immediate post-war period by Josei Toda – one of the few opponents of the Japanese nationalist regime and for this imprisoned from 1943 to 1945 – to offer a new ideal to strive for and to definitively overcome the evil of nationalism.

Here the watershed that arises from the tragedy of the Second World War is to overcome nationalism and perhaps even the very concept of nation, eliminating or softening borders rather than establishing new ones and creating a state organizational form independent of any cultural, religious, ethnic, or personal difference.

Our Italian Constitution, the albeit unfinished institution of the European Community, and also the equally unfinished one of the United Nations Organization are illustrious daughters of those enlightened visions.

Paradoxically, however, the UN itself, with Resolution 181 of 1947, planned the establishment of new borders, defining in Part I, section B, paragraph 3 that “shall proceed to carry out measures for the establishment of the frontiers of the Arab and Jewish States“, sanctioning that a new hard border would from then on forever divide human beings on the basis of their religious beliefs and/or ethnic belonging.

It is not the task of the writer to go into the merits of the historical reasons that led to that Resolution, but the result is today clear for all to see, and its failure should be recognized, placing at the center of the future project a new ideal horizon to aim for, instead of persisting in the error.

Perhaps the time has come to return to the spirit that animated the most enlightened minds after the Second World War, and which identified nationalism as the evil to be overcome.

If we think of the babies who are being born at this precise moment in the land that we now call Israel and Palestine, it is certain that none of them has any idea of the nation in which they are being born, nor of the religion they will practice, nor of any other personal peculiarities will develop over the course of their life.

A modern state should only accommodate this unawareness of birth by ensuring that the opportunities with which those babies will be able to access their personal and social development are independent of their psycho-somatic characteristics, including any disabilities, of the religions they will practice, of their political ideas, economic possibilities and so on.

It makes no sense for a state of this nature to be called either Jewish or Arab.

In this sense, all the crimes committed until now are unfortunately perhaps inevitable consequences of a great blunder, of an enormous mistake made when, at the end of the Second World War, it was conceived a future for this land on a national identitarian basis, which was precisely what had caused the war, rather than creating a brand new open space for it.

Only on the common awareness of having been misled by the nationalist approach at the origin will it be possible, if not to cancel, at least to understand the past and present faults perpetrated by both sides since the beginning and to find a new coexistence that is not the forced one of the victor over the vanquished and for which memory is not an everlasting source of mutual hatred and conflict.

Because sooner or later to live together they will also have to forgive.

Perhaps, if this new utopia begins to travel, if not today, then tomorrow it will be able to come true and finally, the people of that land, Jews, and Arabs together and together with anyone else who will decide to migrate there, will be able to live and protect themselves as belonging to the same humanity, in the same secular and democratic state.