Musei chiusi? Ci salvano le chiese: itinerario tra alcune delle opere più importanti del Medioevo a Roma

In quest'epoca art-free, la nostra sete di arte è appagata dalle chiese. Ecco solo alcuni capolavori dell'epoca storica meno esplorata a Roma.

In quest'epoca art-free, la nostra sete di arte è appagata dalle chiese. Ecco solo alcuni capolavori dell'epoca storica meno esplorata a Roma.

(English translation below)

Ogni volta che passo davanti a una chiesa che non conosco entro a dare un’occhiata, perché non c’è chiesa che non custodisca almeno un’opera degna di essere ammirata. Magari nascosta dietro qualche paramento e qualche oggetto liturgico, magari non illuminata a dovere. Ma quasi sempre c’indovino, e la mia domanda d’arte è appagata. Il duomo di Tuscania (VT), tanto per dirne una, nasconde, in un’absidiola tenuta sempre buia, un meraviglioso polittico quattrocentesco di Andrea di Bartolo, considerato uno degli artisti più significativi della pittura senese tra la fine del Trecento e la prima metà del Quattrocento. Sta lì, al buio, dietro una grata, e nessuno se ne accorge. Altre opere dello stesso autore sono esposte al Walters Art Museum di Baltimora, alla Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, al Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza di Madrid, alla Pinacoteca di Brera a Milano. Tanto per essere chiari.

A tal proposito, pare che la città con più chiese al mondo sia Roma. E in quest’epoca art-free, in cui i musei e le mostre sono inaccessibili, sono proprio le chiese a garantire la sopravvivenza per noi che viviamo anche di arte. E non c’è città migliore di Roma per respirare vere e proprie boccate di arte, con piccoli o grandi capolavori nascosti tra le colonne e i pilastri di architetture solenni ed antiche. Non bisogna pagare alcun biglietto, ma attrezzati delle sole doti del rispetto e della curiosità, si può entrare gratuitamente nei più antichi luoghi di culto e santuari della città per inebriarsi di mosaici, marmi, pale d’altare ed affreschi, facendo un viaggio tra i più grandi artisti del nostro tempo.

Ma non ci soffermeremo sulla Roma barocca o neoclassica, nè su quella rinascimentale. Sarebbe troppo facile: ci mettiamo piuttosto in cerca del medioevo romano, quell’epoca più nascosta e segreta, occultata dalla monumentalità dei secoli successivi.

Certo, un viaggio del genere non può non partire dalle grandi basiliche, come Santa Maria Maggiore, dove il medioevo è ancora fortemente presente: qui i mosaici del V secolo d.C. e il meraviglioso pavimento cosmatesco costituiscono un’abbinata incantevole che già da sola varrebbe un cospicuo biglietto d’ingresso. E invece entriamo gratis e restiamo tutto il tempo che ci pare. Ma piuttosto che lasciarci abbagliare dal soffitto rinascimentale in legno dorato scolpito da Giuliano da Sangallo (che pure meriterebbe un articolo a sé), andiamo a cercare il presepe di Arnolfo di Cambio, uno dei più antichi al mondo: è un’opera scultorea di straordinaria teatralità realizzata sul finire del XIII secolo da questo eccellente scultore e architetto italiano che ha saputo rendere, attraverso il panneggio degli abiti e l’espressività dei visi, un plastico di raro realismo.

In Santa Maria in Trastevere sono i mosaici ad incantarci: e questi non possono sfuggire a nessuno, perché decorano non solo la facciata esterna della chiesa, con una maestosa Vergine in trono tra sante vergini, ma anche l’interno, con scene tratte dalla vita di Maria. Un complesso musivo realizzato dal grande artista Pietro Cavallini nel XIII secolo, che stordisce per la forza dei colori e la luminosità delle scene.

Ma c’è una chiesa che non è sugli itinerari classici della capitale, e che più di tutte esprime ancora oggi la forza artistica dei luoghi di culto del medioevo romano: la Basilica dei Santi Quattro Coronati. Non è una chiesa per tutti, ma solo per chi sa meritarla. Non solo perchè per raggiungerla bisogna snobbare il Colosseo lasciandoselo alle spalle e inerpicarsi su per il Celio, ma anche perché tra le tante basiliche della zona, come San Giovanni in Laterano, San Clemente e San Pietro in Vincoli, quella dei Quattro Coronati rischia di passare inosservata.

La prima sorpresa è proprio nell’architettura esterna: sembra più un castello che una chiesa. E forse anche per questo può sfuggire a chi è in cerca di facciate a salienti e campanili. Ci appare infatti con un’architettura quasi militare, perché fu edificata inizialmente come monastero fortificato, e si articola in varie componenti: la basilica vera e propria, la cripta, il convento, il chiostro con le sue raffinate colonnine ioniche e corinzie, e il palazzo cardinalizio. Il complesso è gestito dalla comunità monastica delle agostiniane che amano definirsi “donne disarmate che sfidano l’individualismo con la tessitura paziente della comunione”.

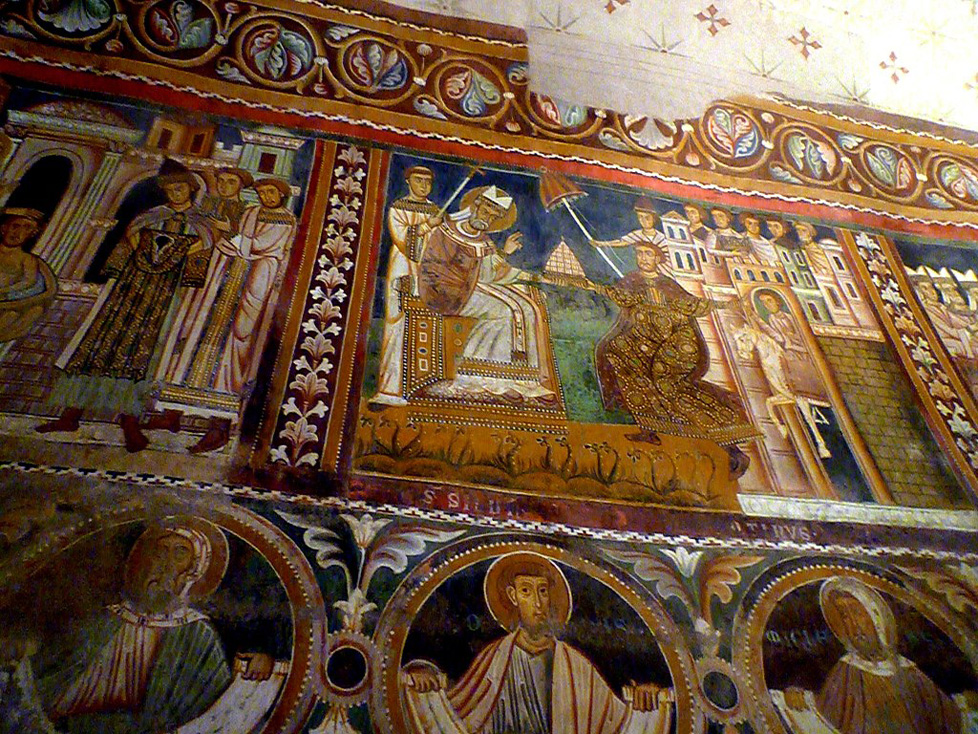

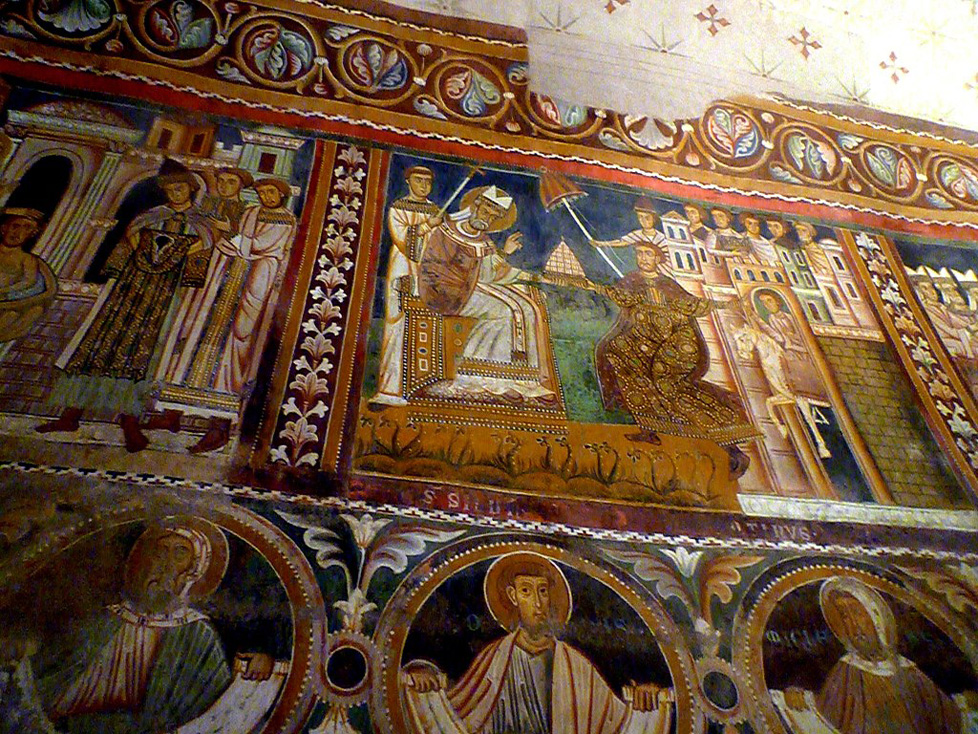

Ma quali sono le unicità artistiche di questo antico luogo di culto? Intanto ha un’abside unica nel suo genere, perché include e abbraccia tutte e tre le navate della chiesa, secondo un modello architettonico quanto mai raro. Poi conserva due matronei che sono gli ultimi costruiti a Roma per ospitare le donne durante le celebrazioni, e risalgono addirittura all’XI secolo. Vanta un pavimento cosmatesco di rara bellezza, dove il disegno del quinconce (il simbolo del numero cinque sui dadi) non adempie solo ad una funzione decorativa, ma anche celebrativa, perchè ogni cerchio indica il punto dove si dovevano posizionare i celebranti durante le cerimonie. Infine custodisce preziosi affreschi duecenteschi d’influenza bizantineggiante, pregiotteschi, con storie di Papa Silvestro e dell’Imperatore Costantino I.

Quanto al nome, ci sono poche certezze: secondo una leggenda, la chiesa fu intitolata a quattro marmorari di fede cristiana che, sotto l’ultima persecuzione di Diocleziano, si rifiutarono di scolpire le statue di divinità pagane, e per questo furono martirizzati. Quattro umili scalpellini del medioevo romano i cui nomi sono già un capolavoro dell’onomastica antica: Castorio, Sinfroniano, Claudio e Nicostrato, e che oggi sono diventati i santi patroni delle corporazioni edili e delle arti murarie.

ENGLISH VERSION

In this art-free age, our thirst for art is satisfied by the churches. Here are just a few masterpieces of the less explored historical era of Rome.

Whenever I see a church that I don’t know, I take a look, because there is no church that does not keep at least one work worthy of admiration. Maybe hidden behind some vestments and some liturgical objects, maybe not properly illuminated. But I’m almost always right, and my request for art is satisfied. The cathedral of Tuscania (VT), just to name one, hides, in an apsidiole that is always kept dark, a wonderful fifteenth-century polyptych by Andrea di Bartolo, considered one of the most significant artists of Sienese painting between the end of the fourteenth century and the first half of the fifteenth century. It is there, in the dark, behind a grate, and nobody notices it. Other works by the same author are exhibited at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, at the National Picture Gallery in Siena, at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Just to be clear.

In this regard, it seems that the city with the most churches in the world is Rome. And in this art-free period, in which museums and exhibitions are inaccessible, it is the churches that guarantee survival for us who also live on art. And there is no better city than Rome to breathe real mouthfuls of art, with small or large masterpieces hidden among the columns and pillars of solemn and ancient architecture. You do not have to pay any ticket, but equipped only with the qualities of respect and curiosity, you can enter for free in the most ancient places of worship and sanctuaries of the city to get drunk with mosaics, marbles, altarpieces and frescoes, making a journey among the greatest artists of our time.

But we will not speak of Baroque or Neoclassical Rome, nor of Renaissance Rome. It would be too easy: we rather look for medieval Rome, the most hidden and secret, hidden by the monumentality of the following centuries.

Of course, such a journey cannot fail to start from the great basilicas, such as Santa Maria Maggiore, where the Middle Ages are still strongly present: here the mosaics of the 5th century AD. and the marvellous Cosmatesque floor make up an enchanting combination that alone would be worth a substantial entrance fee. And instead, we enter for free and stay as long as we want. But rather than let ourselves be dazzled by the Renaissance ceiling in gilded wood sculpted by Giuliano da Sangallo (which also deserves an article in itself), let’s look for the Arnolfo di Cambio nativity scene, one of the oldest in the world: the sculptural work is dramatically theatrical: created at the end of the thirteenth century by this excellent Italian sculptor and architect who was able to make a work of rare realism through the drapery of the clothes and the expressiveness of the faces.

In Santa Maria in Trastevere, there are mosaics to enchant us: and these cannot escape anyone, because they decorate not only the external facade of the church, with a majestic Virgin enthroned among virgin saints but also the interior, with scenes from the life of Mary. A mosaic complex created by the great artist Pietro Cavallini in the thirteenth century, which stuns for the strength of the colours and the brightness of the scenes.

But there is a church that is not on the classic itineraries of the capital, and which more than all still expresses the artistic force of the places of worship of the Roman Middle Ages: the Basilica of the Santi Quattro Coronati. It is not a church for everyone, but only for those who know how to deserve it. Not only because to reach it you have to snub the Colosseum leaving it behind and climb up the Celio, but also because among the many basilicas in the area, such as San Giovanni in Laterano, San Clemente and San Pietro in Vincoli, that of the Quattro Coronati is likely to pass unnoticed.

The first surprise is in the external architecture: it looks more like a castle than a church. And perhaps also for this reason it can escape those in search of salient facades and bell towers. It appears to us in fact with almost military architecture, because it was initially built as a fortified monastery, and is divided into various components: the basilica, the crypt, the convent, the cloister with its refined Ionic and Corinthian columns, and the cardinal’s palace. The complex is managed by the monastic community of Augustinians who like to define themselves as “unarmed women who challenge individualism with the patient weaving of communion”.

But what are the artistic uniqueness of this ancient place of worship? It has a unique apse of its kind because it includes and embraces all three naves of the church, according to an extremely rare architectural model. Then it preserves two women’s galleries which are the last built in Rome to house women during the celebrations, and date back to the 11th century. It boasts a Cosmatesque floor of rare beauty, where the design of the quincunx (the symbol of the number five on the dice) not only fulfills a decorative function but also a celebratory one, because each circle indicates the point where the celebrants had to be positioned during the ceremonies. Finally, it houses precious thirteenth-century frescoes of Byzantine influence, previous to Giotto, with stories of Pope Sylvester and Emperor Constantine I.

As for the name, there are few certainties: according to a legend, the church was dedicated to four marble workers of Christian faith who, under the latest persecution of Diocletian, refused to carve the statues of pagan divinities, and for this, they were martyred. Four humble medieval stonemasons whose names are already a masterpiece of ancient onomastics: Castorio, Sinfroniano, Claudio and Nicostrato, and who today have become the patron saints of the building and masonry guilds.